What my childhood bully taught me about Nigel Farage and the power of saying sorry

As the Reform leader shrugs off claims about racist schoolyard taunts, saying he hasn’t worried for a single moment about hurting anyone, Jonathan Margolis recalls the lifelong scars left by similar abuse – and the redemption that came with a single act of honesty

Last night, I was swapping matey WhatsApps with an old school pal. He was on holiday in South Africa and was just back from the beach; I was on a bus in the cold London rain. It was warm, friendly stuff – I’d say banter, but that word feels tainted these days – between two blokes who have known each other for more than 50 years.

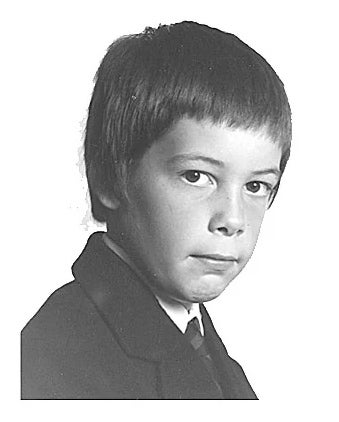

But in the case of my “old friend” and me, there had been a rather significant gap of half a century when we were very much not in touch. The man, John Dickens, a charming and liberal-minded retired headteacher in Swindon, had been an obsessively antisemitic bully in our schooldays. When Nigel “Banter” Farage was accused of using similar racist and antisemitic slurs at school, I decided to get back in touch with Dickens to tell him how his behaviour had affected me and where he got all this nastiness from.

In a new interview with Laura Kuenssberg, Farage said he had not “for a single moment worried about whether he upset anyone”, saying: “I think there were two people who said they were hurt, all right, and if they genuinely were then that’s a pity and I’m sorry, but never, ever did I intend to hurt anybody. Never have.”

As Kuenssberg has since suggested, it has the flavour of the classic political apology – sorry if anyone felt hurt by what happened all those years ago.

Now, Nige mate, let me tell you what it actually feels like. What it is like for reasonably ordinary kids to be confronted with vile racist insults from unpleasant older boys in highly polished Cadet Force boots. And how hollow it sounds when those insults are later dismissed as meaningless.

You should know, Nige, I’m not what you might regard as an “oversensitive” Jew, seeing antisemitism in everything anyone says, especially about Israel. But the hurt I felt as a child was very real. My tormentor’s antisemitic heckling unsettled me deeply and lingered for decades afterwards.

When I finally confronted him, I fully expected that, like Farage, Dickens would dismiss it as schoolboy joshing – that he hadn’t meant anything by it, hadn’t realised it caused pain, or might say he couldn’t even remember doing it.

I could not have been more wrong. Unlike Farage, and in one of the most remarkable acts of decency I have witnessed, my school nemesis apologised profusely. On hearing my voice, and without prompting, he raised some of the awful things he had said and tried to explain what had been going on in his life. We had been 11, he said, and he had been trying to look tough in front of older boys.

I accepted his explanation. We talked and talked. We later shared a wonderful lunch together and are now firm friends. I wrote about this in The Independent last Christmas Eve.

John is a humble, decent man who did what anyone with integrity and character should do when confronting an embarrassing past – though few actually manage it.

Farage, by contrast, has repeatedly rejected allegations that he behaved in a racist or antisemitic way at school, arguing that the claims relate to events decades ago and describing the atmosphere as “banter” or typical schoolboy behaviour. He has also dismissed accounts from former contemporaries who recall offensive remarks, suggesting some critics may have had political motivations.

Farage has, over time, varied his characterisation of these accusations – at points describing them as “made-up fantasies”, while more recently offering qualified expressions of regret if offence was caused.

This time, speaking to Kuenssberg, Farage has addressed the allegations in a relatively dismissive manner, downplaying behaviour that several former classmates have described publicly as racist and intimidating.

Even though the young John Dickens was, by comparison, less extreme in his behaviour – no talk of gas chambers, no “go back to your own country” rhetoric – I never forgot what he said to me barely 20 years after the Holocaust had ended.

Before he started on me, I had never experienced antisemitic remarks. It was shocking and bewildering. I could not understand it – especially the sneering stereotypes about Jews and money. Ironically, my parents at the time were embarrassed by what they saw as the flashiness of some of our Jewish neighbours.

The experience marked me so deeply that, later in life, I sometimes pretended to be Greek – helped by my Greek-sounding surname – simply to avoid similar hostility. In a strange way, it prepared me for later encounters with far more explicit and vicious antisemitism, which has resurfaced in recent years.

What Farage appears not to grasp is that, had he been honest from the outset – as John Dickens was – much of this reputational archaeology might never have happened. All he had to do was what my former bully said:

“I want to come right out publicly and say how embarrassed and ashamed I am about how I behaved back then – and how regretful I am about the stupid, vicious things I used to say.”

Had Farage spoken in those terms, he might have had a chance of claiming moral ground. He might even have earned a degree of respect – perhaps even from me. Instead, I am left wondering whether he has resisted full acknowledgement because some of his fanbase admire that version of his past.

To good people, though, I’d say it’s more obvious than ever that Farage is just a fake Trump with bad teeth. Slightly brighter and more pub-able, but a chancer at best who, by his own admission, doesn’t give a moment’s thought about whether he has upset somebody or not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks