Jeremy Corbyn, the Czech agent and the glorious history of right-wing newspapers linking Labour leaders to communist spies

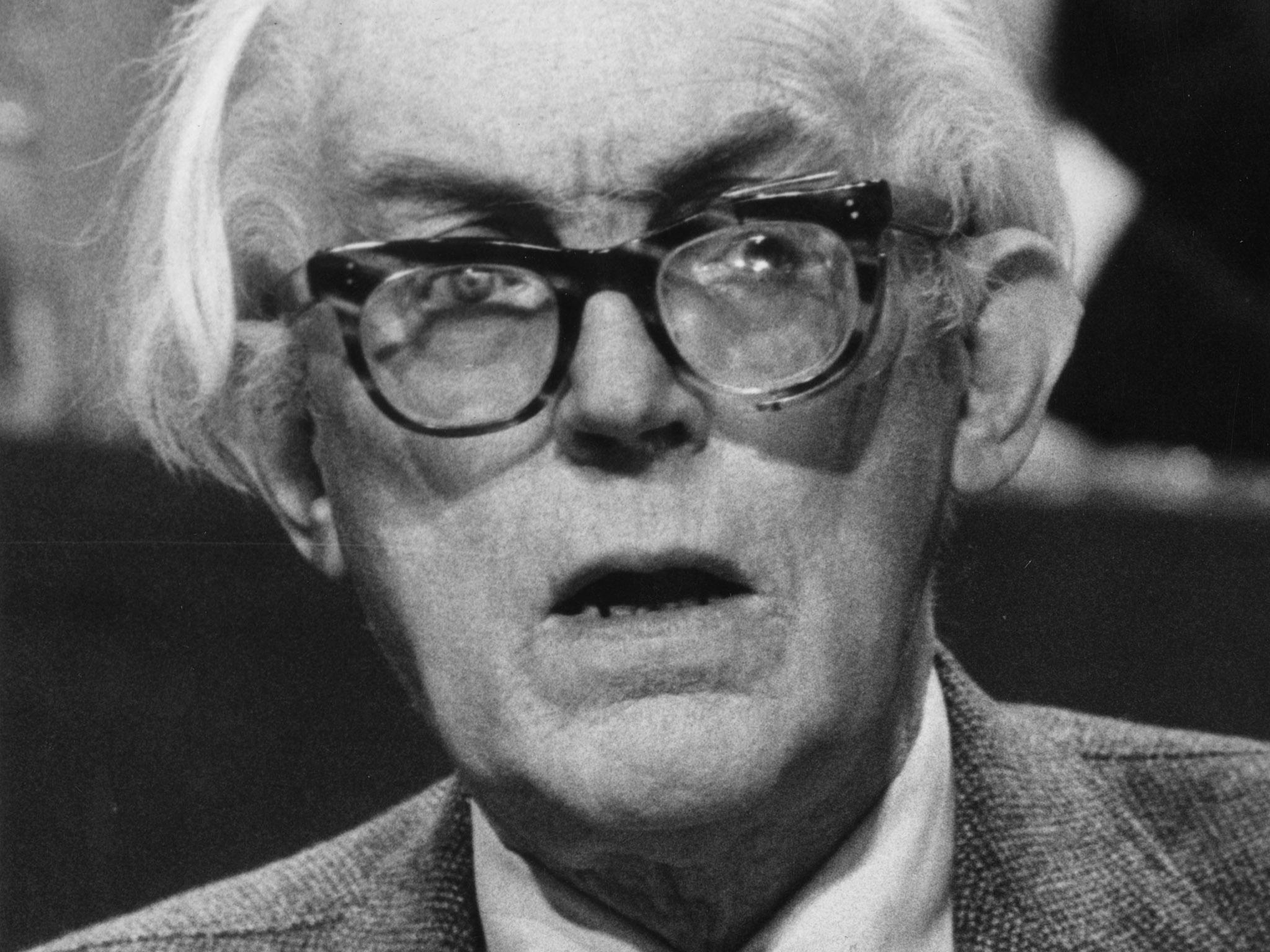

Or how Rupert Murdoch has already paid for one Labour leader's new kitchen (Michael Foot, after he sued for libel when The Sunday Times suggested he was a KGB agent)

To pay for one Labour leader’s kitchen may be regarded as a misfortune; to pay for two Labour leader’s kitchen looks like carelessness.

So spare a thought for newspaper tycoon Rupert Murdoch as controversy swirls around The Sun’s claims about Jeremy Corbyn’s contacts with a Cold War Czech spy.

The last time one of Mr Murdoch’s newspapers, The Sunday Times, claimed a Labour leader, Michael Foot, had got too close to the commies, it didn’t end well.

“KGB: Michael Foot was our agent”, proclaimed The Sunday Times headline of 19 February1995.

Stuff, nonsense and libel, replied Foot, Labour’s left-wing leader between 1980 and 1983.

He sued both the newspaper and Mr Murdoch, winning damages “substantial” enough for him to pay for the new kitchen, plus the celebrations at the Gay Hussar, the Soho restaurant where he had allegedly met his KGB “handlers”, plus a donation to the left-wing magazine Tribune.

It was a triumph so fondly remembered that 13 years later, in what would turn out to be his last published interview before his death, Mr Foot welcomed the New Statesman into the kitchen of his beautiful Hampstead home, recalled how Mr Murdoch had paid for it, and laughed.

Now, as Mr Corbyn issues categoric denials, some have suggested he should follow Mr Foot and sue over The Sun’s story that in 1986 he met Czech spy Jan Sarkocy, was given the code-name COB, and “briefed evil [Communist] regime of clampdown by British intelligence”.

“When The Sunday Times falsely accused Michael Foot of being a Soviet ‘agent of influence’ he sued, won, and bought a new kitchen,” said Paul Richards, a former adviser to Labour ministers. “I assume Corbyn will now do the same?”

Whether that happens, remains to be seen. But there are certainly similarities between the Foot and Corbyn stories.

For one thing they do seem to reflect the obvious: that right-wing newspapers can rarely resist the chance to portray a Labour leader as a dangerous leftie who threatens national security.

That much was also suggested by another Sunday Times story about yet another Labour leader, Neil Kinnock.

During the 1992 election campaign, The Sunday Times advertised the contents of its next newspaper with posters outside newsagents proclaiming: “Kinnock’s Kremlin connection”.

This one, followed by other newspapers using headlines like “Kinnock and the Commies”, revealed – if that is the right word – that Mr Kinnock had met the Soviet ambassador in 1984 and expressed an enthusiasm for unilateral nuclear disarmament.

This, though, was not altogether surprising, given that in 1984 unilateral disarmament was the openly published, official policy of the Labour Party (as it would be until 1989 when Mr Kinnock persuaded his colleagues to ditch it).

The story could fairly easily be dismissed by Labour as the kind of smear that always happens in the fever of an election campaign.

The Foot and Corbyn stories, though, demanded other explanations.

In 1995 The Sunday Times alleged that Foot, during his time editing Tribune in the Sixties, had been an “agent of influence”, accepting funds from the KGB for his efforts to shape British public opinion.

In giving him a code name, the KGB did at least show more imagination than the Czechs who called Corbyn COB, although given that Foot was a journalist at the time, he might not have been flattered had he known that the Russians were calling him Boot.

That, though, was a key point: in the same way that The Sun did not state that Mr Corbyn was a paid-up, fully active, fully aware secret agent, The Sunday Times was soon making clear it was not alleging Foot was a spy, or even that he knew the KGB regarded him as an “agent of influence” - let alone what his code name was.

Instead, hours after the story appeared, Sunday Times editor John Witherow told the BBC it was not his paper that was saying Foot had been a KGB agent - that allegation, he admitted, might be "utter rubbish".

The Sunday Times, Mr Witherow stressed, was merely saying that the KGB believed Foot was an agent.

Which was widely seen as something of a climb down from a three-page spread and the headline “KGB: Michael Foot was our agent”.

(Although, to be fair, “Some in the KGB thought Foot was their agent of influence, although they may have been wrong and they never regarded him as a communist spy” does not a snappy or sexy headline make.)

In admitting that the allegation Foot was a KGB agent might have been “utter rubbish”, Mr Witherow might also have hit upon another potential problem for the stories about both Labour leaders.

This could, perhaps, be loosely described as “need to impress the boss syndrome” – as The Independent discovered in 1995, when it went to Russia to follow up The Sunday Times story, and met former Soviet spy Mikhail Lyubimov.

Yes, he admitted, he did have lunches with Foot in the Gay Hussar, under his cover as Soviet embassy press attaché. But, Lyubimov confessed, he was under pressure from Moscow to justify his salary (and lunch expenses). Soviet central planning, it seemed, extended even to intelligence gathering.

“Like collective farm managers we had to report a good harvest,” Lyubimov told The Independent. “If we had no real agents, we mentioned agents of influence instead. Inside the secret services, and not just the KGB, there is always a lot of fantasy."

There was a similar confession from Viktor Kubeykin, who ran the Labour party and trade union desk at the KGB's London station during the 1970s.

He told The Independent he had spent most of his time cutting out clippings from English newspapers and using cocktail party chat to pad out what were in fact pretty thin reports to Moscow.

Hence, it seemed, the obsession with "agents of influence".

"Many new terms were invented to show we were doing something,” admitted Mr Kubeykin. “It was all just a camouflage for doing nothing, a bureaucratic game. The more people you mentioned, the more credit you got, the higher your promotion."

It does seem reasonable to at least wonder whether similar forces might have been at work when Jan met Jeremy for a cup of tea in the House of Commons in November 1986.

The way Jan Sarkocy wrote it up may well have impressed his bosses.

“He [Corbyn] seems to be the right person for fulfilling the task and giving information,” said Sarkocy in one of the memos found in the archive of the Statni Bezpecnost (StB) Czech secret police force. “He has an active supply of information on British intelligence services.”

According to the files, however, the “active supply of information on British intelligence services” seemed to consist of Mr Corbyn discussing, not something from the heart of MI6 in the style of Kim Philby, but a cutting from the Sunday People newspaper, containing a story about MI5.

So you could indeed say the Labour leader briefed the “evil regime” about a clampdown by British intelligence.

But you could also say the same about the Sunday People, available for purchase by any UK-based communist spy, without the extra expense of the £1 tube fare that Sarkocy supposedly claimed for one of his meetings with Corbyn.

Having said that, if you didn’t meet Corbyn, how on earth could you have known, as Sarkocy did, that he was “Negative towards USA, as well as the current politics of the [Thatcher] Conservative Government”?

The files on Crobyn, the director of the Czech security forces archive has explained to the BBC, never got beyond classifying him as a person of interest.

But some have argued, if he met Jan Sarkocy at all, albeit thinking he was a diplomat, Mr Corbyn was very naïve.

Similar things were said about Mr Foot.

In 2010 after Foot had died, removing the possibility of further libel action, Charles Moore of the Telegraph revealed what he had been told by Oleg Gordievsky, the KGB defector whose unedited autobiography manuscript had inspired the 1995 Sunday Times story.

Posing as diplomats, Mr Moore reported, the KGB agents met Foot regularly for nearly 20 years, slipping money into his pocket in a way which allowed him to ignore it.

Mr Moore, reporting what Gordievsky had told him, said Foot would reveal which politicians and trade union leaders were pro-Soviet, while his Russian friends passed him pre-written articles about unilateral nuclear disarmament that he could publish in Tribune, without acknowledging the source.

The contact ended before Foot became Labour leader, but, Mr Moore concluded, Foot had been a “shockingly naïve ‘useful idiot’”.

Mr Moore did add the caveat that “Foot would not have known he was considered an agent. That was an internal classification of the KGB – a scalp for the bureaucracy. There is no evidence he passed on state secrets.”

“It is not clear why Foot took the cash,” Mr Moore added, “But he probably did not blow it on himself. Most likely, he used it to pay petty bills for Tribune.”

Mr Moore may have got the last bit right. In 2013 the Tribune itself published an article explaining that Foot, as a magazine editor, had been lunching people he regarded as journalistic contacts (not KGB spies):

“In fact,” the magazine said, “What Foot had done was accept Soviet journalistic contacts’ contributions to the bill after lunch at the Gay Hussar, and put the money into the Tribune ‘slush fund’, a venerable institution that provided the float for the bar at the paper’s end-of-year party.”

But if there are similarities in the Foot and Corbyn stories, there are also important differences.

One potential difference seems to be that with Foot, The Sunday Times may have oversold a story provided by a source, Gordievsky, who was, as John Witherow put it, “accurate to an almost pedantic degree".

Indeed, when Gordievsky’s book was published, (after the lawyers had crawled over every word of the manuscript), it came with the warning: “The fact that someone was regarded as an agent of influence meant no more than that it was how the KGB regarded them.”

He even confessed to occasionally suffering from need to impress the boss syndrome himself.

The ageing trade unionist Jack Jones was, Gordievsky wrote, “absolutely useless” as a source of secret information, but he wrote up one report of a meeting with him so artfully that it received gushing praise from his less than sober, less than intelligent boss in Moscow.

“By careful reporting,” Gordievsky wrote, “Success can be created out of very little.”

Which does prompt you to wonder what Jan Sarkocy thinks about those reports he wrote for his bosses in the 1980s.

So far, it’s hard to detect any public acknowledgement that careful reporting of, say, meeting a left-wing backbench MP, can create success out of very little.

Nor does one necessarily get the sense of a source who is “accurate to an almost pedantic degree”.

Mr Sarkocy has gone on to tell other newspapers – not The Sun – that the files in the Czech security archive tell nowhere near the whole story.

He has told The Sunday Telegraph that from Corbyn he and his colleagues “obtained good information that we could use”.

He also appears to have told a Slovakian tabloid enquiring about the nature of this good information: “I'll tell you this. I knew what Thatcher would have for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and what she would wear next day.”

Barring the explanation that Jeremy Corbyn and Margaret Thatcher were secret star-crossed lovers, it is possible Mr Sarkocy was conflating information he was receiving from the Labour MP with intelligence he was getting – or claiming to get – from other sources.

That still leaves the question of what to make of his apparent insistence, in the same interview, that he and the Czech intelligence services somehow helped organise the 1988 “Free Nelson Mandela” concert at Wembley. Or Live Aid. It wasn’t entirely clear which concert Mr Sarkocy seemed to be claiming credit for.

But the Labour Party has made up its mind about him.

“The former Cold War Czechoslovak agent Jan Sarkocy is a fantasist, whose claims are entirely false and becoming more absurd by the day,” a party spokesman has said. “His account of his meeting with Jeremy was false 30 years ago, is false now and has no credibility whatsoever.”

Perhaps the charge that has the most chance of sticking to Jeremy Corbyn is The Sun’s original one, of naivety.

But even Tories can be suspected of naivety.

When he visited Russia as Prime Minister in 2011, David Cameron delighted in telling the story of how when visiting the Black Sea coast on his gap year trip to Russia in 1985, he was approached by “two Russians, speaking perfect English, [who] took me out to lunch and dinner and asked me about what I thought about England”.

This, Mr Cameron surmised, may have been an “interview” to see whether he could be recruited as a KGB agent.

Four years later, however, Russian secret service sources seemed to provide a more prosaic explanation of what had happened to young Mr Cameron and his travelling companion.

Komsomolskaya Pravda quoted secret service sources as saying the two English-speaking Russians were after Western goods to sell on the black market … and the company of “two nice-looking British guys”.

This wasn’t an attempted KGB hook-up, the sources said, but “there was a gay motive”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks