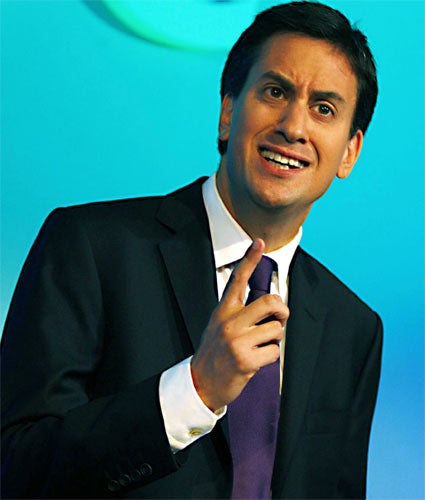

Miliband tries to keep his distance as unions come out swinging

The Labour leader is in an unenviable position with his backers as another winter of discontent looms

When Labour leaders address the TUC conference, they are normally portrayed by the media as either being in the pockets of the trade unions or having a bloody great row with them.

Yesterday, Ed Miliband tried to steer a middle course. He is instinctively more sympathetic to the unions than Tony Blair or even Gordon Brown. Most of his 30-minute speech was positive about the unions' role. But he deeply disappointed the delegates by refusing to support their planned strikes over cuts to public sector pensions this winter. In his eyes, he was being a candid friend. In their eyes, he failed the acid test.

A year ago, it was the unions "wot won it" when he defeated his older brother, David, for the Labour leadership. Now, as many of his predecessors have found, the union brothers are causing strife inside in the Labour family.

Mr Miliband is in a bit of a pickle over the unions' power inside the party. As part of a much wider "Refounding Labour" review, aimed at reconnecting the party with local communities, he would like to dilute the unions' 50 per cent share of the votes at Labour's annual conference, and possibly their strength in leadership elections, where they hold a third of the votes, the same proportion as the party's members and MPs.

Some union leaders warned him against turning the review into a Blair-like "virility test" designed to make him look strong. His problem is that the unions are flexing their muscles too. Mr Miliband does not want this month's Labour conference in Liverpool to be dominated by a fight with the unions – one he could lose.

He wants to reach a consensus with union bosses, but one said yesterday: "We are not going to be bounced. We want a proper debate."

But delaying a decision until next year might make Mr Miliband look weak. One Labour MP said: "Having marched us up to the top of the hill, he would be marching us down again."

Time is running out because the Labour conference begins on September 25. Crunch time will probably be a meeting of the party's national executive committee next Tuesday. Officially, there are no proposals on the table yet. Behind the scenes, lots of different options are being kicked around in the hope that the unions will buy one.

Mr Miliband has a possible escape hatch: the publication next month of a review of political funding by the independent Committee on Standards in Public Life. It is considering a £10,000 cap on donations to all parties, which would be compensated by more funding from taxpayers. This would potentially have huge implications for Labour's link with its union founders, who contribute more than 80 per cent of the party's donations. So Labour could argue that it would be wrong to rush into decisions about the unions' voting power while their funding role may be thrown into doubt.

It is ironic that Mr Miliband has got himself into a stand-off with the unions. "They have a special place in Ed's heart," one aide said.

His conciliatory message to the TUC was that he wanted to do business differently from Mr Blair. He told the unions they needed to modernise to join the Government and business in shaping the "new economy" but deliberately avoided the "modernise or die" mantra of the Blairites. He believes economic "change" must not be imposed on people like globalisation but must be "change for people."

He sees a genuine partnership role for the unions and has a lot of time for their ideas – such as encouraging employers to pay a living wage higher than the national minimum wage. Yesterday, his broadly constructive approach was overshadowed by his stance on the planned strikes over pensions.

Allies insist he was not saying he would never support industrial action, only that it was a very last resort and should not take place while negotiations continue. That did not cut much ice with the unions. Even moderates were miffed, saying the next wave of co-ordinated strikes would happen after talks with the Government had broken down, which both sides expect to happen. Mr Miliband was not spoiling for a fight yesterday. But he won't lose too much sleep over his rough ride, which sends a signal to the wider electorate that he may not be in the unions' pockets after all.

Labour and the unions

James Callaghan

Sunny Jim had good relations with the union barons and counted on them to deliver the block vote at party conferences, which they generally did. But below them, a growing army of shop stewards and union members were in revolt over wage restraint. It was union activists, not their leaders, who brought about the Winter of Discontent.

Michael Foot

Callaghan's successor was considered a good friend of the union movement. While Minister of Employment, he had acted as a conduit between unions and government at a time of great industrial unrest. Some argued that he foresaw splits in the Labour Party, and did his best to preserve the party as a left-wing alliance with the unions.

Neil Kinnock

Having been propelled into the leadership by two union bosses, Ron Todd and Clive Jenkins, Kinnock then tried to end the system that made it too easy for local parties to sack sitting MPs. But his attempt to bring one-member, one-vote threatened the power of local union officials, who inflicted a defeat on Kinnock at his first party conference as leader.

John Smith

Smith greatly benefited from union backing in the leadership election that followed Kinnock's resignation, yet he managed to succeed where Kinnock had failed. He removed the union block vote not just from the process for selecting Labour parliamentary candidates, but also from party leadership elections.

Tony Blair

Because the rules had changed, Blair owed nothing to the unions when he was elected Labour leader. If they had had a block vote, they would not have cast it for him, and they had not yet worked out how to intervene in other ways. When Blair spoke at TUC, he was usually heard in sullen silence.

Gordon Brown

Brown clashed with the unions over public spending cuts during his short term as Prime Minister. His speech to the TUC in 2009, in which he warned of "hard choices", was met with a muted response from union leaders.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks