How the ‘humanitarian’ crisis in the NHS is paving the way for private healthcare

Officials are scrambling to define the narrative on the latest wave of misery

It has been a calamitous winter inside the NHS. Last week, three people tragically died at Worcestershire Royal hospital with a women dying of a heart attack after waiting for 35 hours on a trolley. A similar picture has developed across the country with patients on trolleys due to lack of beds, many hospital trusts on red alert and ambulances missing targets for life-threatening emergencies. The British Red Cross declared a humanitarian crisis in the NHS.

The return of the Red Cross to Europe, over the last few years, for the first time since the Second World War is a terrible indicator of the toll austerity is taking. Wall-to-wall coverage and acres of column inches have generally failed to examine the root causes. Health journalists and correspondents seem perfectly content to recycle the crisis mantra. This is extremely convenient for the government and vested interests. What is missing from this picture is that the NHS crisis is manufactured by deliberate policies of cuts and privatisation.

The NHS will have endured an unprecedented nearly £40bn in cuts by 2020. Prime Minister Theresa May’s response – notably in last Sunday’s interview with Sophy Ridge on Sky News – has been to downplay the crisis. Hunt followed suit and his statement to the Commons on Monday was a typical masterclass in deflecting the blame. The initial response in the government playbook was to change the subject to mental health. Hunt also raised the possibility of axing the 4-hour A&E waiting target.

Undoubtedly, there is a significant crisis in mental healthcare as it is underfunded proportionate to what it represents as a percentage of NHS care. However, the unfolding winter crisis has been one of emergency and hospital care. Mental health is worth dwelling on, though, because it represents a dire warning for the future of the NHS. A programme of Care in the Community was launched in the 1980s accompanied by the closure of inpatient facilities and wards. The result has been chronic shortage of psychiatric beds with patients, including children, forced to travel hundreds of miles if they require inpatient care.

Mental health has also been a testing ground for privatisation with whole swathes outsourced to the private sector. The NHS Five Year Forward View now proposes a similar model for physical health. The Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) represent £22bn in efficiency savings with downgrade or closure plans for tens of hospital trusts. Hospital care will therefore be consolidated at large centres. The Dalton review suggests that these super hospitals can be run either by NHS trusts or the private sector.

The same programme is being applied to general practice. More than 650 GP surgeries have already been closed, merged or taken over since 2010 and the Royal College of General Practitioners warns that up to a further 600 surgeries face closure by 2020. The General Practice Forward View document pushed for networks of federated organisations in April. On the face of it, this all sounds like a reasonable proposition. However, this new model of integrated or accountable care is being imported from US healthcare; specifically organisations, such as Kaiser Permanente. Hunt even cited Kaiser Permanente as an exemplary model before a parliamentary committee.

Integrated healthcare is designed to minimise access to expensive hospital care and to deliver care in the community. Care in the community sounds again like a reasonable proposition. Yet, there appear to be no plans for significant investment in community or GP services. Quite the opposite has been rolled out with hefty cuts to social care leading to bed blocking.

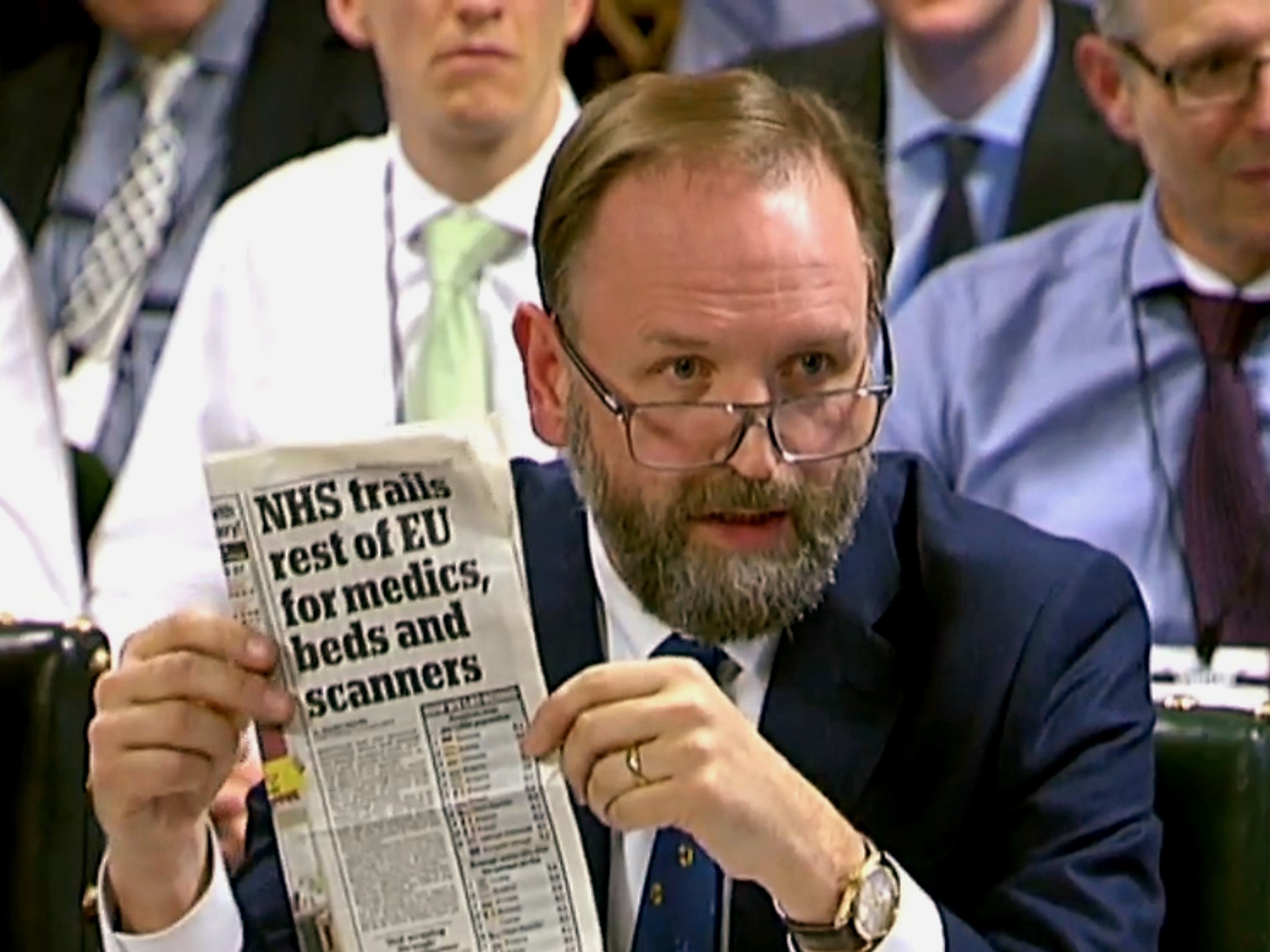

In fact, the NHS bed crisis has been generated by decades of ward closures. More than half of NHS beds have been closed since the 1980s. Unsurprisingly, NHS bed to population ratios are now below some Eastern European countries. The prospect of more cuts and hospital closures and downgrades is hardly an enticing one. This is likely to translate as a mixed model of care with the expansion of private health insurance entirely in keeping with proposals by David Cameron’s health advisor Nick Seddon. Seddon previously wrote in The Daily Telegraph that the NHS should merge with insurance companies and those who can pay should contribute towards their healthcare.

Yet as became apparent with the Government’s response this week, the one thing putting the brakes on privatisation plans is political expediency. The STPs may well hit the buffers – local campaign groups are already mobilising rapidly as communities face the stark possibility of losing their local hospital. The new year has certainly not started well for the NHS but there is another way of looking at all this. It’s all going to plan. One is reminded of Mark Britnell’s comments a few years ago at a private equity conference that the NHS would be shown “no mercy” and that it would become a “state insurance provider, not a state deliverer” of care.

It looks like this prophecy is coming true. Britnell is a former senior Department of Health civil servant before he went off to work for KPMG. A narrative of crisis fits in with the story being spun by private healthcare lobbyists – namely that the NHS is unsustainable and unaffordable and that it will need to shift towards new models of funding and care.

Chris Hopson, chief executive of NHS Providers, told the Public Accounts Committee this week that the current NHS model of universal healthcare may no longer be sustainable. The problem is that the current NHS model is not the original one of publicly run, provided, and funded care. The NHS is now a market system with the logo used to conceal a plethora of private sector activity. Hospitals are set up as foundation trusts or semi-independent businesses with corporate management and are allowed to make up to half their income from private patients.

Many are privately financed and run by corporate consortia. The Private Finance Initiative (PFI) means that banks, such as RBS and HSBC, have controlling stakes in NHS hospitals and it has been reported that HSBC even owns three NHS hospitals outright. This is the crux of the matter. The market system with accelerating private sector involvement has escalated costs.

The response of the shadow Health Secretary Jon Ashworth for a larger funding settlement is all well and good but it is a second order issue. The primary issue is the removal of the market and private sector involvement. Market forces and privatisation are siphoning tens of billions out of the NHS budget as corporate profits. The limited internal market costs between £4.5 up to £10bn a year. The extensive market – consisting of hospital foundation trusts, payment tariffs, contract tendering and other market processes – is likely to cost even more.

Department of Health figures show that private sector outsourcing now accounts for £8.7bn a year or 7.6 per cent of the budget excluding general practice, dentistry and community pharmacy. The key point on private sector outsourcing is that, as a rule, profits are not reinvested. PFI represents a further £2bn a year and NHS hospitals will pay up to £80bn eventually in PFI debts. The total UK PFI debt for all infrastructure is more than £300bn or four times the size of the budget deficit, which was used to justify austerity in the first place. It is worth recalling that too-big-to-fail banks, such as RBS, which played a significant role in the financial crisis, are profiting from PFI. Hospital trusts are paying millions each week on PFI and, as a result, a majority are running into deficit.

Much was made this week of NHS chief executive Simon Stevens “speaking truth to power” when he told the Public Accounts Committee that the NHS was not getting the funding it needed. In reality, Stevens was one of the architects of privatisation by expanding the internal market into an extensive market as adviser to New Labour Health Secretary Alan Milburn and then as adviser to Tony Blair. Stevens eventually went off to work for UnitedHealth in the US – one of the largest private healthcare and insurance corporations. He has now returned through the revolving door at the helm of the NHS. This is part of a bigger pattern of corporate capture of policy making across government.

In his parliamentary statement, Hunt played the blame game emphasising that A&E cannot simply cater for every whim and need. This has been the preferred narrative diverting blame onto the concept of the NHS, NHS staff, lifestyle choices of patients and an ageing population. In fact, the public model of universal healthcare or socialised medicine is the most cost-effective. The ageing population and rising treatment costs are a factor all over the world. As for lifestyle choices, health outcomes are directly correlated to socio-economic status so that the more affluent you are, the better your health is generally.

Richmond CCG now appears to be launching a consultation on rationing all manner of treatment ranging from hip and knee operations, cataracts, hearing aids, IVF, over-the-counter medicines to treatment for obese patients and smokers. This fits in with a wider picture of rationing being ramped up across the country. Increasingly, it is looking like this winter crisis is being used to prepare the public for the expansion of charging and private health insurance.

Lo and behold, last year Parliament quietly set up a House of Lords NHS Sustainability Committee looking into exactly this question and it is due to report by March. One cannot pre-empt their conclusions but it would not exactly be surprising, in the current climate, if they recommend a shift towards charging and private health insurance. Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell have made the NHS Reinstatement Bill part of official Labour party policy, which flies in the face of decades of cross-party consensus around increasing marketisation and privatisation of the NHS.

This legislation would repeal the Health and Social Care Act, attempt to cancel or restructure PFI debts, reverse private sector involvement and disband the market inside the NHS. Restoring the NHS as a public healthcare system through these measures would release tens of billions of pounds to be spent on patient care. A positive vision for the future of a 21st-century NHS would mean that it is neither exclusively controlled by the state or the market but a truly public healthcare system, meaning that it is publicly funded, provided and accountable with doctors, nurses, allied health professionals, patients and communities running services.

‘How to Dismantle the NHS in 10 Easy Steps’ by Youssef El-Gingihy is published by Zero Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks