Will Nicola Sturgeon’s push for a new independence referendum be successful?

There are three fundamental problems with indyref2, and none are new, writes Sean O’Grady

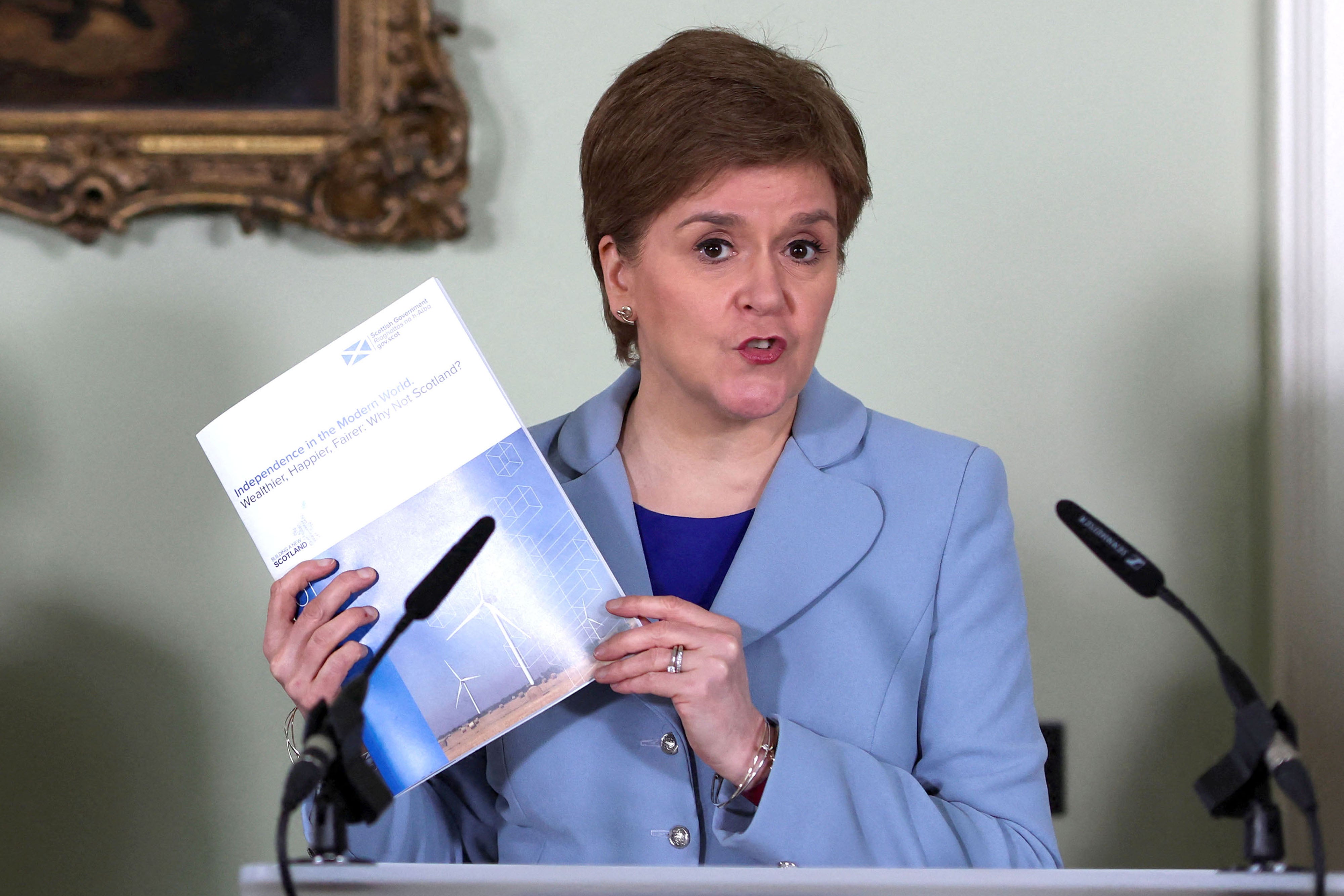

At first sight it is difficult to understand why Nicola Sturgeon, first minster of Scotland, is launching her latest campaign for a referendum on independence for Scotland right now.

This is not because it is a bad time due to the state of Brexit, the war in Ukraine or the cost of living crisis, as her opponents suggest. The SNP view, which is perfectly plausible, is that Scotland could make a better job of meeting these challenges if it were in charge of its own destiny, and not being governed, at least in some of the most important areas of policy, by a Conservative party that hasn’t won an election in Scotland since 1955.

No. The mystery is more about tactics and strategy than the merits of the case, which will be explored in a series of policy papers the Scottish government intends to publish in the coming weeks. These will include its proposals on crucial matters such as the currency (sterling, euro or Scottish pound), joining the EU, and the “soft” border with England (analogous to the Northern Ireland-Ireland border issue), as well as Scotland’s fiscal position.

So why has Sturgeon called for a poll now? And why has she set herself a deadline for it of the end of next year, and thus constructed something of a political cage for herself?

There are three fundamental problems with indyref2, and none are new. First, the British government, along with the parliament in Westminster – ie Boris Johnson – has the sole authority to delegate the holding of a lawful referendum to the Scottish government. It did so once, in 2013, for the first referendum in 2014, in which the “Yes” side lost by 55 per cent to 45 per cent. Johnson, like Theresa May before him, has since resolutely refused to make the necessary arrangements to revisit the question, even post-Brexit. Sturgeon argues that she has a democratic mandate; Johnson insists that the 2014 referendum was decisive for a generation.

Legally, it seems watertight, because Section 30 of the Scotland Act 1998, which provides for such delegation of power to call a referendum if approved by both houses of parliament in Westminster as well as the Scottish parliament, was very tightly drawn, with exactly such awkward eventualities in mind.

Unlike the equivalent “border poll” clause in the Northern Ireland devolution legislation, there is no room for argument about whether a refusal for Scotland is reasonable or based on any particular evidence. It is “bald”.

Sturgeon asked Johnson for a “Section 30” arrangement for a referendum in 2019, and he replied in terms from which he never wavers: “You and your predecessor [Alex Salmond] made a personal promise that the 2014 independence referendum was a ‘once in a generation’ vote. The people of Scotland voted decisively on that promise to keep our United Kingdom together, a result which both the Scottish and UK governments committed to respect in the Edinburgh Agreement.

“The UK government will continue to uphold the democratic decision of the Scottish people and the promise that you made to them. For that reason, I cannot agree to any request for a transfer of power that would lead to further independence referendums.”

Answering, the first minister argued it was “not politically sustainable for any Westminster government to stand in the way of the right of the people of Scotland to decide their own future and to seek to block the clear democratic mandate for an independence referendum”.

It is by no means clear why Johnson would suddenly change his mind. In fact, he would dearly love to embarrass Sturgeon by saying “no” indefinitely, so that she is forced to break a promise that it is seemingly beyond her power to keep. (Alternatively, she knows this full well, but it suits her to be scrapping with Johnson, and making him look unreasonable.)

The second puzzle about the second referendum is the fact that the polling is not obviously going Sturgeon’s way. It’s clear that the Scottish elections provided a majority in the parliament for two pro-independence parties, the SNP and the Scottish Greens, but that doesn’t necessarily mean a majority for independence, as the polls indicate – they are currently around the 48 per cent Yes, 52 per cent No mark, eerily enough. To be fairly certain of winning, Sturgeon would be looking for a more substantial and sustained lead, with the independence side having a “6” in front of its rating. It is possible that the erratic behaviour of the UK government and the cost of living crisis will push Scottish opinion further towards separation; but the mess left after the EU referendum, especially in Northern Ireland, might have the opposite effect.

Third, it is unclear why Sturgeon has seemingly changed her mind about holding an informal, unofficial, or (in some eyes) rogue referendum, backed only by Scottish parliamentary approval. In the past, she was unequivocal about needing a Section 30 basis that would place indyref2 “beyond effective legal challenge”, like the one in 2014. For years, her predecessor, Alex Salmond, has argued that the Scottish could arrange for a “consultative”, non-binding referendum (though, of course, no referendum is strictly “binding”, at least not on a British parliament – as the Brexit referendum proved, exhaustively). Now Sturgeon is hinting that she has an alternative legal route to a referendum without Westminster approval – but is coy about the details. Many are sceptical.

An alternative way of building democratic momentum would be to organise a constitutional convention to agree a “Claim of Right”. In 2020, Sturgeon proposed a convention of elected representatives from all parties to prepare such a document, echoing the 1689 original and a reborn 1989 version that led, eventually, to devolution and the re-establishment of a Scottish parliament in Edinburgh. However, this convention idea seems to have been dropped for lack of wider support.

An unofficial independence referendum, assuming it could be held, and assuming it went Sturgeon’s way, would be a powerful tool in the quest for independence. Arguably, such a poll would enjoy a higher turnout among pro-independence voters than unionists, and it would add muscle to the debate.

But in any case, no Conservative prime minister would take much public heed of it, and it would be derided as a stunt without legal standing. Back in 2012, the then advocate general for Scotland, Lord (Jim) Wallace, a former Scottish Lib Dem leader, declared: “The Scottish parliament has no power to legislate for a referendum on independence. There are important consequences which follow from this. One is that to proceed with a referendum that is outside of its legal powers would be to act contrary to the rule of law.” It might thus be stymied by order of the courts.

Still, whether a “consultative” referendum went ahead or not, it would allow Sturgeon to tell her impatient internal critics to shut up, because she would have done exactly as they wanted. Although it would have no immediate effect, it would be of immense propaganda value. But Johnson would still find it easy to just say “no”.

The more intriguing question, as the next election nears, is what the attitude of the Labour leader would be to such an unofficial or consultative poll; and what, if any, concessions Labour would make to the SNP in the case of a hung parliament at Westminster. The SNP might make a Section 30 independence referendum a non-negotiable condition of support; but that would risk allowing a Conservative government back in, which is probably not what most Scots would like to happen.

The upshot of all this is that independence doesn’t seem much nearer than it did in 2014, and the best route to getting the Tories out of Scotland’s hair is to vote Labour, for the simple reason that the SNP can win every Scottish seat in every election, and there’ll still be a Tory in No 10, as the last 12 years (not to mention 1979 to 1997) have proved.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks