Britain's Political Revolution: Canterbury, Corbyn and a seismic change in the landscape

In the first of a three-part series from his Kent home city, Patrick Cockburn drills deep into the shifting tectonics beneath our political landscape

Political earthquakes, terrorist outrages and man-made disaster are pounding Britain so frequently these days that it is scarcely possible to take in the significance of one before the next is upon us.

There has been the referendum on Brexit, the fall of one prime minister and the rise of another, three suicide attacks, the general election with a completely unexpected outcome and the Grenfell Tower disaster.

The political landscape in Britain is changing in ways and to a degree that is little understood, but will very likely shape the life of the country for decades to come.

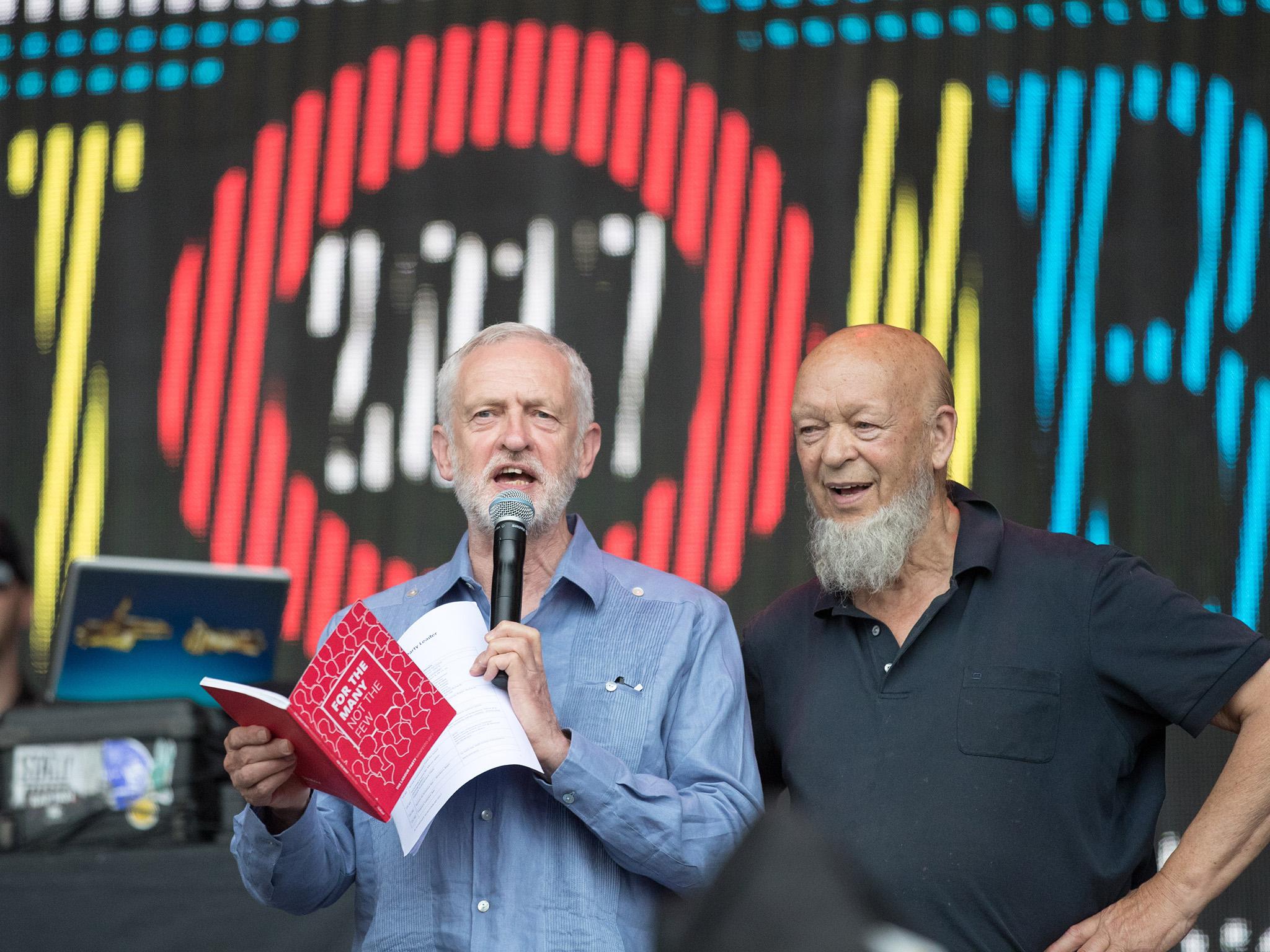

All the pundits turned out to be wrong about the outcome of the election on 8 June. They portrayed Jeremy Corbyn as a pariah leading Labour to inevitable destruction, but three weeks later he leads a rejuvenated party, is ahead of Theresa May in the polls for the first time and was being applauded at the weekend by tens of thousands of fans at Glastonbury as an anti-establishment icon.

How did all this happen? In times of radical change, past experience becomes a misleading guide to future developments. The Independent decided to take a single part of the country and try to drill down deep to see if the tectonic plates are really in motion and, if so, in what direction. No part of Britain is wholly typical of the rest, but Canterbury parliamentary constituency is a good place to start because it provided one of the biggest shocks on election night.

For the first time in 176 years, its voters returned a non-Conservative MP by the narrowest of margins. Ever since a young Queen Victoria was on the throne in 1841, the Conservatives had been able to hold on to their stronghold in and around Canterbury, even during the Labour landslides of 1945 and 1997. But when the votes were counted and recounted on 8 June, it turned out that the ancient cathedral city behind its medieval walls, the fashionable seaside resort of Whitstable and the picture-postcard villages amid the orchards of the North Downs had elected a Labour MP by just 187 votes.

Local Labour supporters were cock-a-hoop at their victory, which they had not expected despite positive indications during the campaign. The new MP, Rosie Duffield, 45, the single mother of two sons and once an assistant teacher in the village of Littlebourne outside Canterbury, was disbelieving about her success right up to the last moment. “I was very, very surprised,” she says. “I thought that we might reduce their majority, but not that we would win.”

Another local Labour activist says that he had seen signs of growing support for Labour, but he still could not quite shake off the feeling that there was something inevitable about a Conservative win, because “you feel that you are up against 100 years of history”. In the event, Duffield increased Labour’s share of the vote by 20.5 per cent to 25,572 compared with the 25,385 ballots cast for Sir Julian Brazier, 63, who had been MP for the constituency for 30 years.

Brazier says he blames his defeat on two events during the campaign, “one of which I could do nothing about, and another which was my own fault”. He says the first development was a greatly increased turn out of students who voted Labour and the second was his failure “to use social media enough to engage the electorate until the last days of the campaign.” He is reported as having said separately that an overconfident Conservative Central Office had damaged his chances by sending him to campaign for other Conservative candidates holding seats it deemed to be more at risk than Canterbury.

As an explanation for his defeat, Brazier’s analysis is not to be discounted, but it is oversimplified. Young voters as a whole, and not just students, are going over to Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party and are turning out to vote in unprecedented numbers. Canterbury has two big universities: the University of Kent and Christ Church University, in each of which there are about 19,000 students. They voted more heavily and more strongly for Labour than in previous elections.

But Christian Turner, 21, a second-year undergraduate at Christ Church, who campaigned for Labour, points out that at his university “exams concluded on Friday 26 May”. Come the election, most of the students had gone to homes outside the constituency. Among his friends, Turner says that only the most politically committed used postal votes and he suspects the others did not vote in Canterbury or did not vote at all. At Kent University, straddling a long hill overlooking Canterbury from the north, more students were present, but, even so, Ben Hickman, a lecturer there and Labour Party activist, estimates that half of them had left by 8 June. Of those who remained, plenty did vote as shown by pictures of queues outside a polling booth on campus.

Many Conservatives feel it unfair that they should be swamped by the student vote. A former Lord Mayor, George Metcalfe, complained about students being able to decide “the political climate” of a constituency that held by the Conservatives for so long; he demanded that they vote in the places they originally come from. Other Conservatives believe it unwise for their party to further alienate students, who are likely to go on voting in Canterbury and are essential to the economy of the city. Brazier takes solace in the fact that he is not the only victim of a surge in student numbers and participation in the poll, remarking that “the Conservatives have lost all the university cities”.

It would be good news for the Conservatives in Canterbury and in the rest of the country if newly militant students, in a sort of throwback to the 1960s, were their only problem. But conversations in Canterbury and national opinion polls both confirm that age and education are the new great dividing line in British society, largely but not entirely replacing class divisions. A YouGov survey of 50,000 voters in the general election showed that, under the age of 47, more people voted Labour than Conservative, while above that age the reverse is true.

One early sign of a Labour breakthrough in Canterbury on election day was that there were as many prams as walking sticks to be seen in the polling stations. Brazier blames himself for not using social media to communicate with and energise his supporters, but this may not be realistic option for the Conservatives. Their core vote is concentred among the late middle-aged and elderly, who are less likely use social media than younger Labour supporters who wholly depend on it to send and receive information. In talking to Conservatives, it is noticeable that they often refer to what they have read in the newspapers while Labour supporters seldom do so, finding everything they want to know online.

In the aftermath of election, many commentators claimed that younger voters were bought up by Labour with generous offers, such as the abolition of tuition fees or action on student debt. But a better explanation is that Corbyn and his more radical Labour Party fit in with a pervasive anti-establishment mood.

Material concerns alone do not explain what happened. Charlie Mower, 18, from Whitstable, an articulate organiser of younger Labour supporters in his last year in school before going up to university, says that Labour attracts the pre-university young because of its dissident “style of politics”. More substantive issues, such as tuition fees, may become a motive later on, but are not as important as often imagined. As will be shown in a later article in this series, students are much more worried about exorbitant rents for their accommodation in Canterbury, which they have to pay cash down, rather than tuition fees that they might have to pay in future.

Mower added that tabloid and television vilification of Corbyn either passed unnoticed among the young, because it did not penetrate the social media they favour, or increased his credibility as an opponent of a toxic status quo. The YouGov survey cited above shows that 66 per cent of 18- and 19-year-olds voted Labour while only 19 per cent voted Conservative.

More encouraging from the Conservative point of view, reports of the mass mobilisation of younger voters through the social media are premature, since only 57 per cent of 18- and 19-year-olds and 59 per cent of 20- to 24-year-olds voted. This compares with a 77 per cent turnout of those between 60 and 69 and 84 per cent for those over 70.

Political interest and activism is growing fast in Canterbury. The metropolitan media, which patronisingly cites Brenda of Bristol’s declared exhaustion with repeated national votes as a sign of the national mood, has, not for the first time, got this exactly the wrong way round. Not all of this activism is new, nor is it always confined to the young. A week after the election there was a furiously angry meeting of about 300 people in a school in Canterbury to protest the temporary downgrading of the local hospital, the Kent and Canterbury, which is suspected of being a covert bureaucratic bid to shut it permanently. Most of those attending looked middle-aged or older and the agitation has been going on for a long time.

But there are many other signs that more and more people are being drawn into politics. One witness to this from an unusual perspective is Jeremy Macleod, who looks as if he is in his late twenties, and whose job is taking visitors in a punt along the different branches of the Stour River in and around Canterbury. “I am quite political and my friends used to laugh at me for going on about politics,” he says. “But now they talk about politics all the time themselves and exchange information through Facebook. I am sure all of them voted Labour.” He says that he has noticed that many of his customers sitting in his punt have started to talk about politics among themselves, as he propels them along under the willow trees and the ancient city walls, something they never did in the past.

Young Labour activists emphasise the “huge impact” of the Grenfell Tower fire on 14 June in turbocharging many election issues. Charlie Mower says that the disaster “very much discredits Thatcherism and the response to it marks the end of that kind of economics”. Everybody he speaks to sees the tragedy as a “rich versus poor” event. He is encouraged that even a Labour MP such as Harriet Harman, whom he sees as being very much on the right of the party, is calling for the requisitioning of property in Kensington for use by Grenfell Tower survivors, thereby demonstrating “a seismic shift” to the left in the political centre of gravity.

Jack Brooks, 23, who is at the Centre for European Studies at Christ Church, agrees that the disaster is affecting young voters because “it hits on so many themes of the left-wing/anti-austerity narrative”. Social media platforms he favours are full of clips of Corbyn hugging surviving residents and of Theresa May looking frosty and disengaged. He says that the episode has “done wonders for Jeremy Corbyn’s deity like status for young people”.

He stresses another point which underlines the extent to which the difficulty and expense of finding somewhere to live determines political choices in Canterbury and everywhere else. He explains that “many young upwardly mobile members of my generation are living in or looking to live un accommodation just like Grenfell Tower, as it’s the perfect balance between just about affordable, but also in London where all the good jobs are”. The young as a whole, and not just students, are subject to intense pressures on their standard of living.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks