Why the NHS junior doctors strike probably won’t mean more patients dying

Previous strikes haven't increased mortality, according to observed evidence

Junior doctors working in the NHS in England have voted to go on strike on 1 December, 8 December and 16 of December.

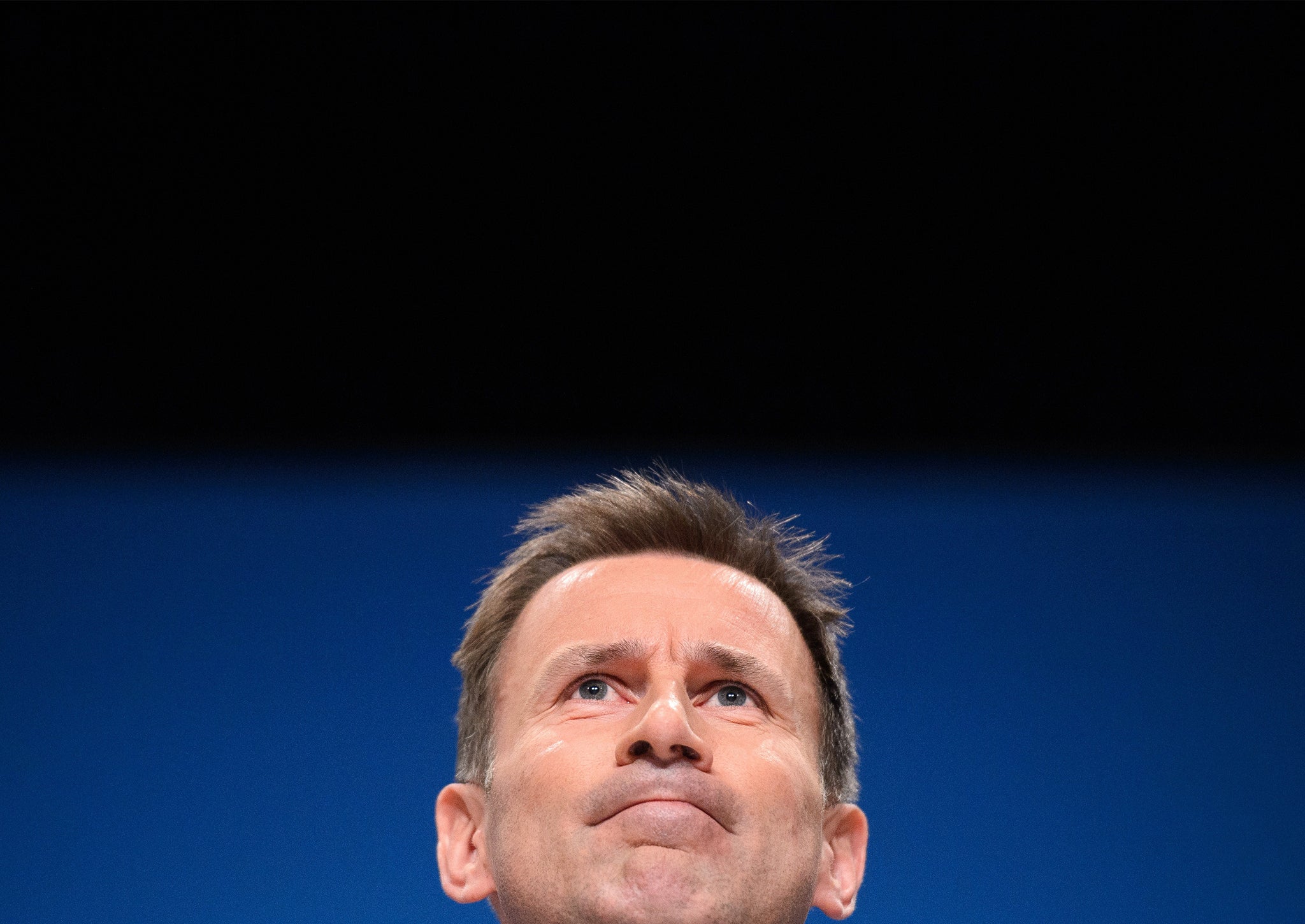

The doctors voted by 98 per cent to go on strike over changes to their contracts proposed by the Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt.

Mr Hunt says the industrial action is likely to put “vulnerable patients” at risk while Dr Mark Porter, chair of the British Medical Association’s council said it could be carried out without harming patient safety.

Who is right, Jeremy Hunt or the BMA?

According to the latest evidence, the BMA has a point: previous doctors’ strikes in other countries haven’t tended to increase death rates. To understand why this is, we need to look at the academic evidence.

In 2008, researchers published a “meta study” on the effects of doctors’ strikes in the journal Social Science and Medicine.

This study didn’t focus on one strike in particular, but instead gathered together all previous evidence from seven different studies that analysed specific strikes around the world from 1976 and 2003.

Some of these strikes were fairly substantial, with the longest lasting seventeen weeks. The shortest was nine days, which is three times longer than the three (detached) days NHS junior doctors are proposing.

The researchers found that none of the strikes had increased death rates. Somewhat counter-intuitively, sometimes fewer people died.

“All reported that mortality either stayed the same or decreased during, and in some cases, after the strike,” they concluded.

“None found that mortality increased during the weeks of the strikes compared to other time periods.”

Why don’t more people die?

The researchers suggested several reasons for the flat mortality rates during doctors’ strike.

They say the most important was that non-emergency, or “elective” surgery is stopped during the strike and staff are re-allocated to deal with emergencies.

This influx of clinicians to prop up emergency care means that A&E rooms do not tend to collapse during strikes.

Furthermore, a large proportion of deaths during a hospital’s working day actually come from people undergoing elective surgery, which can be quite risky – so these deaths are taken out of the picture.

In some cases doctors also provided care outside of hospitals, setting up ad-hoc aid stations to treat people who needed help. Many of the strikes so far were also not universally observed.

What is important in these cases is that health service managers are given time to plan – which the BMA has done.

Could a strike in the NHS be different?

There are some complicating factors. As stated above, none of the strikes studied were universally observed by doctors – if every doctor went on strike there would be no one to re-allocate to provide emergency care.

In December’s planned stoppage, junior doctors have voted overwhelmingly – by 98 per cent – to go on strike. In a 76 per cent turnout this means participation is likely to be very high.

On the other hand, non-junior doctors are not going on strike and will be able to provide emergency services. There is, however, anecdotal evidence that more senior medics are very sympathetic to juniors’ cause. How they act will be key.

It could also be the case that a rise in emergency deaths is offset or partially offset by a fall in elective deaths, meaning emergency care specifically is more risky.

The NHS is also expecting a winter crisis this year, with the King’s Fund, Nuffield Trust and Health Foundation warning the Government that one is “inevitable”. If the health service is at breaking point, further strains on its resources may not do it any good.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks