Another Country: Whatever happened to rural England?

The English village is dying – and with it a way of life stretching back centuries. Richard Askwith laments the accelerating loss of our rural heritage

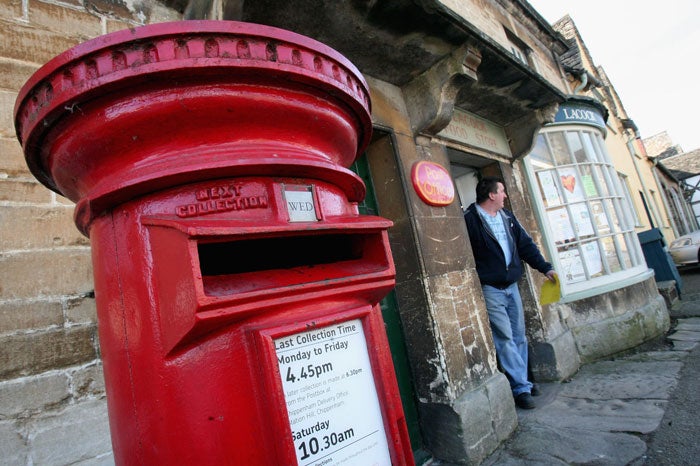

You cannot go far in rural England without running into a row about postal services. Wootton, in west Oxfordshire, is as good an example as any.

A pretty, grey-stone village of about 260 households, it has a post office counter at the back of a little village shop – itself recently saved from closure by a community initiative, and now staffed by local volunteers.

You wouldn't call it a busy post office, but nor is it deserted: the part-time postmaster expects about 18 customers a morning, of whom two or three, typically, come less for business reasons than for social ones. (The day I visited, an elderly villager had just asked him to repair her radio for her.) Twenty or 30 pensioners get their pensions from it, the school next door uses it for banking, and pretty much everyone drops in sometimes for a chat.

Any day now, however, all this may change. Wootton's is one of 2,500 post offices nationwide that face closure in the name of stemming the subsidised losses of Post Office plc. Villagers have mounted a spirited protest – they had David Cameron down there the other day – but, with 26 other post offices earmarked for closure in Oxfordshire alone, they're not hopeful. The final decision is expected any day now.

For Michael Lowe, who lives alone in a little cottage near the centre of the village, closure would be a catastrophe. He's one of the 20 per cent of villagers who don't drive. "We never had a car when I was growing up. I just never learnt." For the past 34 years he has earned his living from a workshop adjoining his cottage, making and repairing lutes. He does a lot of business by post. "If the post office closes, I'll have to go to Woodstock instead. Unfortunately, we had nearly all our public transport cut off two years ago. If I wanted, say, to post a parcel, I would have to go out at 9.30am, catch the mini-bus, and then the mini-bus goes back at 11.30am, getting me back at 11.40am. So I'd have taken most of the morning off work. Woodstock's a nice place, but I can't afford to spend half a day drinking coffee there, three times a week. I suppose the idea is that everyone who lives in the country should have a car. But that would be very difficult – it's a huge amount of money."

Joan Thomas, whose family have been in the village for "four generations at least", and who lives – as "old" villagers tend to – in an ex-council estate tucked away from the village centre, uses the post office several times a week. "I get my pension there, I get my Oxford Mail there every day, I do the shopping for my father, who's 90. It will be a pity if it goes. It's not just the question of where you're going to get your pension from. It keeps the village alive. It's a community thing – it's where you hear if someone's dying or ill, things like that. We'll cope if it closes, of course, but people would have to think a lot more about other people who can't go by car."

There will be other consequences: more traffic on the roads; more queues in the tiny post office at Woodstock. To those who live in towns and cities, such concerns must seem remote. They are – until you consider the wider context. All over England, the traditional structures of village life are falling away. I know about Wootton because my sister lives there. My own village, about 25 miles away in south Northamptonshire, is untroubled by such controversies, for the good reason that we have completed our full house of rural closures: school, shop, pub, post office. Apart from a little-used church – which shares its vicar with five other villages – Moreton Pinkney has no traditional institutions left.

That doesn't make us in any way remarkable. In the past decade, scarcely a village has escaped such changes. They haven't, on the whole, come about as a result of any conscious policy: they have just happened. But they are symptoms of a huge social revolution that verges, at times, on the tragic.

*****

A couple of years ago, I became mildly obsessed with the idea that rural England was vanishing. It started abruptly. I was standing in our village churchyard, contemplating an old gravestone whose lettering had been worn to illegibility by time. After trying and failing to decipher it, I began to wonder how and when, precisely, those missing numerals and letters had disappeared. Had they been dislodged by an especially violent gust of wind, or a series of particularly big raindrops? Had some ravenous micro-organism taken too many bites? Presumably, in such cases, tiny bits keep dropping off until, one day, so much has gone that the rest can't be imagined, unless you remember what it originally said.

There is never an identifiable moment at which the point of no return is reached – just many moments afterwards, when you can say with certainty that the point of no return was passed long ago. And the thought struck me that something similar had happened to the traditional life of the countryside.

I wasn't thinking particularly about the physical environment – although there's no doubt that vast swathes of countryside have been irretrievably lost in my lifetime – but, rather, about the cultural environment. It wasn't just pubs, shops and post offices that were disappearing (at a rate, then, of 26, 25 and 12 a month respectively – all three have since accelerated); almost anything that had the character of a solid rural institution seemed to be in precipitate decline.

The old churches were deserted and crumbling (roughly half of those in England are now threatened with closure). Little village schools were in decline (it's hard to quantify this exactly, as many closures are concealed under the guise of amalgamations, but hundreds are in danger from the latest official rationalisation drive). Pubs that survived were no longer smoky locals in which villagers chewed things over, but had turned into "destination" gastropubs frequented by well-heeled outsiders. Many of the surviving shops were delicatessens. As for farms: innumerable farmers had sold off their holdings to urban incomers who used them for leisure rather than agriculture, and 70,000 agricultural jobs had vanished in a decade.

Above all, endless "For Sale" signs bore witness to a huge population shift. My village, by my calculation, was turning over 10 per cent of its population a year. Countrywide, 100,000 people were migrating into the countryside from towns and cities each year – and had been for two decades. That's two million people in 20 years – equivalent to a new person setting up home in the countryside roughly every five minutes; or, if you prefer, a 20-year period that has seen, on average, 45 new attempts to realise a rural dream in each square mile of rural England.

Everywhere I looked – in my own village, in neighbouring villages, in villages I happened to pass through in other parts of the country – the same process of transformation had taken place. There were new extensions and conversions, garages and conservatories, neat hedges, new garden furniture, goals and climbing frames, satellite dishes, electric gates, security lights and burglar alarms – but scarcely any of the slow, bad-toothed, mud-spattered people I thought of as real country people.

Upmarket retail outlets and leisure facilities had sprung up in what used to be green fields; every other person seemed to be working at home providing luxury services such as dog-grooming, party-planning, aromatherapy or life-coaching. And the same chunky, multicoloured necklace of parked cars was draped around everything.

Most of us have been vaguely aware of such developments for years. But the thought that struck me, and has continued to gnaw at me since, was that so much change and loss in such a short space was tantamount to a social tidal wave, in which a whole way of life – and a whole class of traditional country-dwellers – had been swept away.

I found myself thinking of the countryside as a giant graveyard, haunted by the ghosts of a lost tribe that had once imagined that its lifestyle would last for ever. Where others saw desirable villages and charming scenery, I saw the ruins of a collapsed civilisation. Yes, there were people living in them. But they were a new breed, adapting the physical remains of rural England for the purposes of their new, post-rural society – in the same way that, in the fifth and sixth centuries, post-Roman Italians broke and baked the marbles of antiquity to make plaster for their pre-medieval huts.

I was in my mid-forties and had thought of myself as a villager for most of my life. A middle-class villager, certainly, who had spent much of his time in towns and cities; but, even so, someone who always had a village near the heart of his mental landscape: a fixed point of continuity and peace, planted solidly in familiar fields just beyond the edge of my vision, to which I could always return.

In a wider sense, I had also taken for granted a vague idea that, somewhere in the background of my life, there would always be, not just one village, but a whole network of many thousands of villages, each with its own story, its own local families, its own unique landscape and memories and its own peculiar way of saying and doing things... In short, I had imagined rural England, and had blithely gone through life under the impression that it would always be there, like a great rock, with the past clinging to it like lichen.

Yet when I looked around me, it was gone. I began to spend large and arguably ridiculous amounts of time travelling around England, looking for villages whose identities had survived the homogenising forces of modern life and, when I found them, looking for old village people. It proved surprisingly rewarding. The species was less rare than I had imagined, although many considered themselves endangered.

From Cornwall to Northumberland, Cumbria to Suffolk, I met people whose roots in their local soil were as deep as those of the trees and hedgerows around them: people whose family memories, stretching back generations, were also the memories of their communities.

I interviewed many of them in depth, as if they were celebrities, even though, by conventional standards, few had done anything very interesting. "I haven't been very far," one 83-year-old Exmoor farmer told me. "I been to Exeter, though." She had only ever spent one night off her farm. But that, to me, was the interesting thing: that there were still people who had lived their lives on a local stage instead of the global context in which most of us imagine our stories unfolding.

The details of our conversations were largely banal. Yet to me they represented a link to a rural past I had begun to think of as lost. That Exmoor farmer, for example, was one of several people who told me how, when she was growing up, the only form of transport available to her was a pony. "It's open common there," she explained, describing one unaccompanied nocturnal journey, "there's no fences, and it was very foggy. And Father had said don't you pull the rein; let that pony go where she wants to go. So I did that, and it looked like the pony's went wrong, but I didn't pull the rein, and at last we come up to the gate that goes across the main road. I didn't worry after that, because I knew she'd come home all right."

That's hardly a startling anecdote. What startles me is the gulf between that kind of childhood and rural childhoods as they are typically lived today. In the old countryside, childhood was hard – and dangerous – to a degree that a growing number of country-dwellers would struggle to imagine. "I was driving a tractor when I was six," a former farm labourer from Northamptonshire said. "Never went to school. All through summer, everyone would be out on the harvest. Driving tractor was the easiest bit, so that was my job. Never learnt to write nothing – I still can't."

"All I ever knew was hard work," an Oxfordshire saddler told me, explaining how his schooldays were largely taken up with manual work. "We used to spend a lot of time in the harvest fields – your arms would be red-raw from thistles."

An Oxfordshire pensioner remembered how "I started with the horses, ploughing. I just left school. I only did it when the one what was in charge of the horses was sick. Well, these horses, they knew more about the job than what I did. When you turned up at the end, they know where to go back in better than what I did. It was blooming hard work in them days. I used to carry two-hundredweight bags on my back – two and-a-half hundredweight for beans. Of course, now you're not allowed to carry more than half a hundredweight."

The details varied, but the theme of hardship was consistent. A Hampshire thatcher explained how he had been taught how to keep his hands warm on a freezing morning: "You'd break the ice on a water butt and put your hands in it for five minutes. After that they'd be warm all day."

"We could eat," said a fisherman in the Cornish village of Polperro, "but putting clothes on your back was another thing. I remember very well – cardboard don't last very long in the bottoms of shoes, I can tell you that. And I think I must have been about 13 before I realised that you could wipe your arse on specially made paper."

Yet nearly all of the old country-dwellers I met looked back on "the old days" with affection. "We had to make our own fun," said a dairy farmer on Bodmin Moor. "We didn't go all that long away, but we would run wild like. We used to get together, two or three of us, and we used to go out on common and set it on fire and all the likes of that."

A farmer's widow in Nottinghamshire told me how she remembered people whose idea of an evening's entertainment was to sit in a shed chopping sticks. In Northumberland, I met a shepherd whose idea of a well-spent evening, even today, was much the same. "I get obsessed with the stick I'm dressing. That one was a hazel branch. Took me three weeks, off and on."

"We were never bored," said the Oxfordshire saddler. "We never had electricity, or sewers, not until way, way after the war. There was one well to feed 12 houses for water – you used to queue up to get your water. But we all used to play in the road. We'd spin a top, or when the man came from Chipping Norton to kill the pigs – everyone had a pig in their garden – he'd give us the bladder and we'd rinse it out and blow it up like a balloon."

To the modern, townie mind, that doesn't sound like a huge amount of fun. Yet virtually everyone seemed to feel that something precious was being lost. "There was a time round here," the Bodmin dairy-farmer said, "when it was just about all relations. All round the moors, they were all our neighbours, just about all relations. We helped one another out – what one don't have, another may have."

"It was such a wonderful community," recalled a 91-year-old widow in the Yorkshire village of Cherry Burton. "The village people, I won't say they loved one another but they were fond of one another. And you knew exactly if he was ill or if she was ill and all about that, and I don't think there was one door in this village that wasn't open to me. Unfortunately they're all dying out now. The people who come here to live, they don't know anything about the village." I think that was the thing people cared about most: that villages were filling up with people who, through no fault of their own, knew nothing about their local past.

That Polperro fisherman had family memories stretching back to the time when his village was a self-contained kingdom, unconnected to the rest of Cornwall by road and ruled by the notorious smuggler Zephaniah Job. "My great-great-great-grandfather spent nine years in a French prison," he added. "He used to fish off the Channel Islands, and then one day he went as far as the French mainland and was arrested as a spy. Nine years he spent there. But then he came back and had nine children."

And then there was the Dorset hurdle-maker, whose tools were "much older than me" and whose ancestors included seven previous generations of hurdle-makers (all using exactly the same methods) and one of the Tolpuddle Martyrs; and whose great gnarled hands included one misshapen finger he had broken decades ago, stuck back in place with tape and not thought to show to a doctor for 40 years.

"The town's moving into the countryside, that's how I see it," he said. "What's sad is, even people who came from the country, they've been infected with the town mind now. I think perhaps they're a bit ashamed of their background or something."

He was not sentimental about the past: his father was so hungry as a child that he used to sneak into the fields at night to steal milk from cows. None the less, he felt that something was being lost. "It's a shame that everyone's so materialistic. I think our parents, they saw the poverty of the early 20th century, and the war, and they tried to make it better for us, didn't they? But now? I think that people have forgotten something."

Does this have anything to do with post offices? I think it does. It's not that I subscribe to the facile view that the countryside is being spoiled by incomers who should go back where they came from. (On the contrary, many incomers take a leading role in breathing new life into moribund village institutions.) I'm not even certain that the transformation of rural England should be considered a bad thing – although it alarms me that so little of the rural economy is now concerned with the production of food.

But the fact remains that each post office closure, each shop closure, each pub or school closure, represents the dismantling of one more piece of rural permanence; just as, each time an old family moves out and is replaced by incomers, another piece of the collective memory is removed.

In Wootton, Joan Thomas remembers a village that had a baker, a butcher, a shoe-mender, two shops, a farm, a nursery, a mill, a wheelwright, a glover, a carpenter, a policeman with his own police house, and four pubs. Today, it has one pub, one shop and no active farms. Only a few representatives remain of the old, intermarried families – Bugginses, Gubbinses, Caseys, Davises – who once were the village. Joan is realistic. "You can never go back to the village you knew as a girl. You have to adapt." Yet there is something disturbing about the thought that so much has passed away so quickly.

Ronald Blythe, the great chronicler of East Anglian rural life, put it like this when I spoke to him: "The old traditional village life has almost gone, and so swiftly, and has been replaced by 21st-century technology and comforts that are much the same nationwide, whether one lives in the town or the country. Everybody now has television, everybody has fitted carpets, everybody more or less has a computer, everybody has foreign holidays. It is quite amazing to someone like myself who, as a boy, saw the old harvests, and the old poverty – the good and the bad, all more or less vanished."

We pause and doff our caps, metaphorically, each time we hear that another of the surviving handful who fought in the First World War has passed away; not because we yearn for a return to trench warfare, but because there is something solemn about the thought that soon none will remain. So it should be, perhaps, with the old country-people of England. Their world is passing, for better or worse. We should not let it do so without acknowledgement.

Adapted from The Lost Village by Richard Askwith (Ebury Press, £18.99), to be published on 3 April. To order a copy for the special price of £17.09 (free P&P), call Independent Books Direct on 0870 079 8897 or visit www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks