The Big Question: What is the Rosetta Stone, and should Britain return it to Egypt?

Why are we asking this now?

Dr Zahi Hawass, the secretary general of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) and the high priest of all matters archaeological in the Land of the Pharaohs, arrived in London yesterday to further his demand for the return of the Rosetta Stone from the display rooms of the British Museum, where it has been on show since 1802. Dr Hawass has embarked on an international campaign to secure the return of a host of renowned artefacts which he claims were plundered by colonial oppressors and assorted brigands from Egypt's ancient tombs and palaces before ending up in some of the world's most famous museums.

What is so important about a 2,200-year-old slab of granite?

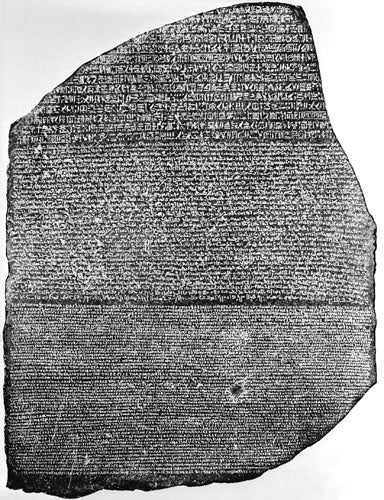

Carved in 196BC, the Rosetta Stone is the linguistic key to deciphering hieroglyphics and probably the single-most important conduit of understanding between the modern world and ancient Egypt. The 1.1m-high stele was covered in carved text bearing three translations of the same written passage. Two of the languages were Egyptian scripts, including one in hieroglyphics, and the remaining text was classical Greek.

Its discovery by a French army engineer in 1799 near the post of Rashid or Rosetta allowed western scholars to translate for the first time a succession of previously undecipherable hieroglyphs using the Greek translation and thus unlock many of the secrets left behind in the myriad carvings and frescos of the pharaonic era. Ironically, the meaning of the text on the stone itself was less than rivetting – it describes the repeal of various taxes by Ptolemy V and instructions on the erection of statues in temples.

What's Dr Hawass's case for returning the Stone?

As with the Greeks and the Elgin Marbles, he considers the stele to be stolen goods and has made it clear, in no uncertain terms, that he considers its continued presence in the British Museum to be a source of shame for the United Kingdom. Speaking in 2003, when his campaign began, Dr Hawass said: "If the British want to be remembered, if they want to restore their reputation, they should volunteer to return the Rosetta Stone because it is the icon of our Egyptian identity." The archaeologist, who has established a fearsome reputation as the self-appointed guardian of Egypt's antiquities since he was made head of the SCA in 2002, claimed this week that Britain had under-valued the stone and kept it in a "dark, badly-lit room" until he expressed an interest in its repatriation.

So was it stolen?

The Rosetta Stone's journey from the sands of an 18th-century desert fort to the hushed halls of the British Museum is indeed clouded by colonial skulduggery. The stone was discovered in July 1799 by Captain Pierre-Francois Bouchard, an engineer in Napoleon's army sent to conquer Egypt a year earlier. The arrival of the British in 1801 and their subsequent defeat of Napoleon's forces led to a dispute between the team of French scientists sent by Paris to collect archaeological finds and the commander of Britain's occupying army, who insisted they be handed over as the spoils of victory. General Jacques-Francois Menou, the French commander, considered the stone to be his private property and hid it.

There are conflicting stories about how it then fell into British hands. One version is that it was seized by a British colonel who carried it away on a gun carriage. Another version is that a British Egyptologist, Edward Clarke, was passed the stone in a Cairo back street by a French counterpart. Either way, there is little or no record of any consultation with the Egyptians. When the stone eventually arrived back in Britain, it bore an inscription painted in white: "Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801."

Why is Dr Hawass so important?

Described by New Yorker magazine as sitting "at the intersection of archaeology, showbusiness and national politics", Dr Hawass is no shrinking violet when it comes to publicising his causes. Clad in his trademark stetson, widely interpreted as a nod to the wardrobe of Indiana Jones, the doctor regularly takes to the airwaves, newspaper columns and cyberspace to outline the latest discoveries in Egypt and maximise the mystique of a past that is worth at least $11bn (£6.7bn) a year to the Egyptian economy. He also likes to batter home his point that "for all of our history our heritage was stolen from us". To date, he has appeared in four feature-length documentaries, written 16 books and likes to tease Omar Sharif, a close friend, that he is the far better known of the two men.

What do other archaeologists think of him?

For a man who makes no secret of relishing controversy, it is unsurprising that he has some detractors. Critics accuse Dr Hawass of being autocratic and harnessing serious archaeology to the yoke of media and popular entertainment. Under his leadership, the SCA has acquired a fearsome reputation for withdrawing accreditation from foreign Egyptologists accused of breaking the organisation's rules, effectively banishing them from making further discoveries. But there is also grudging respect for his efforts to improve the standards of homegrown archaeologists, invest in Egyptian museums and generally gain a greater share of Egypt's past for its own people.

What else does Egypt want back?

Dr Hawass insists he is not looking for the repatriation of every artefact, but his shopping list includes some of the most famous items of Egyptian art held abroad. They include the elegant bust of Queen Nefertiti held by Berlin's Neues Museum, the Dendera Temple Zodiac in the Louvre and a bust of the pyramid builder Ankhaf kept in Boston's Museum of Art.

Are there any precedents for returning artefacts to Cairo?

Dr Hawass claims to have secured the return of some 5,000 artefacts during his SCA tenure. His power was underlined in October when, under threat of the removal of Egyptian co-operation for archaeological expeditions, the Louvre agreed under the direct orders of the French culture minister to return some fragments of written text which were allegedly stolen in the 1980s.

What does the British Museum say?

After decades of diplomatic manoeuvring over disputed items such as the Elgin Marbles, the museum is well-practiced in the art of fending off requests for its most glittering treasures. Underlining its role as a global repository for humanity's cultural achievements, it said: "The Trustees feel strongly that the collection must remain as a whole." Officials also wasted no time in pointing out that Dr Hawass's presence in London, which included a speech to an invited audience at the museum last night, is largely to publicise his latest book.

Is it time we surrendered the Stone?

Yes...

* British ownership of the stone is the result of a colonial dispute, not a deal with the Egyptians

* Egypt has invested £110m on improving its museums and heritage sites

* 200 years of mismanagement and plundering has left Egypt denuded of its most important artefacts

No...

* The British Museum is a global showcase for two million years of shared human history

* Concern remains that priceless artefacts are at risk of damage in Egyptian museums

* Returning it would open the flood gates to similar claims that would empty the BM's display cases

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks