Symbol of unity: the Springbok vs the Protea

The springbok has been the instantly recognisable symbol of South Africa since 1906 and was preserved in the post-apartheid era. Now the ANC wants to replace it and unite all the nation's sporting teams under one symbol – the protea. By Ian Evans

For more than 100 years it has been a powerful symbol in South Africa, first dividing and then uniting a population once riven by racial division. But this weekend could see the springbok kicked into touch as the national rugby union team's emblem and replaced – whisper it quietly in clubhouses – by a flower.

The ruling ANC said it wants to unite all its sporting sides under one emblem and so the leaping antelope which has never been more popular in the Republic, looks set to get its marching orders. The graceful animal has featured on the green and gold rugby shirts of South Africa for 102 years since being adopted during a tour of Britain in 1906-07.

It is said that the team's first captain, Paul Roos, chose the springbok on an impromptu basis to prevent the British press from inventing their own name – nothing new there.

The animal appeared on the left breast pocket and blazer of the green uniform, a colour which had been adopted 10 years before. Commentators at the time said the tour created a sense of national pride back home and helped ease bad feeling over the two Boer Wars.

The first coloured national team used the Springbok as its emblem in 1939 and the first black national team used it in 1950. It has also undergone a few facelifts and leapt in different directions. In 1992, when racial sporting rules were abandoned in South Africa, a wreath of proteas – the country's national flower – was added above the animal.

Minor changes have occurred since but this weekend the ANC may finally signal its demise after a number of threats since first taking power in 1994.

An ANC spokesman, Tiyani Rikhotso, said a decision on a new symbol for South African sport would be taken at a lekgotla, or special meeting. He said: "The decision to unify the sporting codes under one symbol was taken last June and endorsed at our special conference at Polokwane last month. It will be discussed as part of our social transformation policy. Whether it is rugby, cricket, football or netball, we want to see one symbol."

He would not be drawn on what that emblem would be, but conceded that the Protea or the country's colourful flag could feature. "It is no different to your sides in England which have the red cross. We want our new Rainbow Nation to rally under one emblem which represents everyone but I am not going to pre-empt what that's going to be."

It's not the first time the ANC has wanted to get rid of the once-hated springbok emblem. After the election victory in 1994, the ANC wanted it replaced by the protea only for President Nelson Mandela to step in and give special permission for it to be used in the 1995 Rugby World Cup in South Africa. Despite being excluded from organised international competition for nearly 20 years because of apartheid, the Springboks won the tournament. When he made the presentation of the William Webb Ellis Trophy to Francois Pienaar, the team captain, Mr Mandela wore a Springbok shirt and cap – a hugely symbolic gesture on what was once the hallowed Afrikaans turf of Ellis Park, Johannesburg.

After the win, Dan Qeqe, the veteran anti-apartheid sports campaigner and "father of black rugby" in South Africa, said: "I never had the chance to test myself against the white rugby greats, but today we play together, and the Springboks play for all of us."

But despite the sentiment, colour still dominates public debate on team selection in South Africa, with claims and counter-claims over why certain players are picked and not picked.

The predominantly white sports of cricket and rugby are most affected with all appointments – both administrative and playing – pored over for bias or political duplicity.

Last week the Springboks named its first black coach, Peter de Villiers, who took over from the World Cup-winning coach Jake White who was himself dogged by criticism over team selection. The South African Rugby Union president, Oregan Hoskins, said he was the best man for the job but then undermined reasons for the appointment by saying "transformation" also played a part. Getting a straight answer on what transformation means isn't easy, but in layman's terms it means more coloured and black players in the first team with the caveat that they must get in on merit. Confused? You are not alone.

There is no doubt that Mr De Villiers has the coaching credentials to fill the role and, upon taking it, warned players that there would be "no favours" on team selection. Not shy in using the Springbok term, he added: "You dream of being a Springbok player and if you can't be a player you dream of being a Springbok coach and that has become a reality for me now. I am very privileged to be in this position of taking over a great squad of players but this is where the hard work begins. To make wholesale changes would be stupid."

What he probably didn't envisage was a change to the team's name. He declined to talk about the impending move saying that he had "never really thought about it", but Mr Hoskins said he was dismayed. "My personal view is that the Springbok emblem should be retained because it has the ability to unite the nation, as was demonstrated during and after the World Cup," he told a local newspaper.

"I still see all South Africans, of all colours and creeds, wearing the Springbok shirt and jersey around me. I remember when Jake White asked me to address the team and hand out jerseys. I told the players that as a young black person, I supported the All Blacks over the Springboks.

"I spoke about my passion – from anti-Springbok under apartheid to a Springbok supporter in the new era. If the Springbok is eradicated it would impact hugely on South African rugby, in ways that would change rugby for ever and could have catastrophic consequences that would never be redeemable."

That might be a slight exaggeration, but Mr De Villiers' appointment and the demise of the springbok could draw a line under the once-dominant influence of Africa's last white tribe.

Since rugby's early days, the Boers have dominated domestic rugby from their heartlands of the former Transvaal, Natal and Orange Free State. Whereas in the former Cape Province – and in particular present-day Eastern and Western Cape – rugby was more integrated with far more black and especially Cape Coloured – descendants of salev labourers – teams.

During apartheid, racial barriers were still in place for official teams, but mixed sides were tolerated – as long as they played each other. That was not the case in the more Afrikaan-dominated parts of the country where English-speaking South Africans were barely tolerated, let alone those with different coloured skins.

But with pressure for quotas and black stars such as Bryan Habana and J P Peterson in last year's World Cup-winning team, the racial mix is changing – albeit gradually. Local coaches report greater interest among black and coloured children to play rugby instead of football . Disillusionment over domestic football has increased with an under-performing national side and overpaid players not helping enthusiasm in the approach to the World Cup in South Africa in 2010.

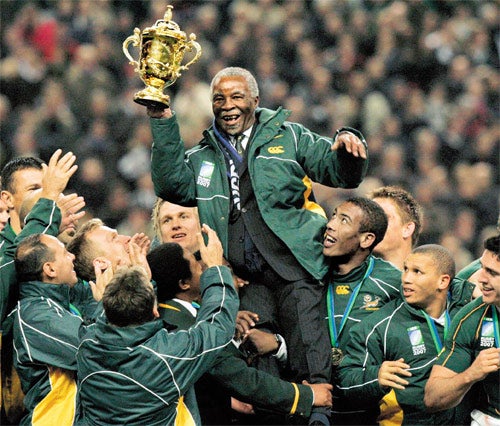

Indeed the national side, Bafana Bafana, will also face a name change and one man who will support that is President Thabo Mbeki. After returning with the victorious Springboks from Paris in October, he questioned the nickname which means The Boys, The Boys.

"What kind of a name is it? I don't think it is fit for a senior national team or for the hosts of the 2010 Fifa World Cup," he told a South African radio station. "We need to revisit the names of teams like Bafana Bafana, Banyana Banyana (The Girls, The Girls) Amaglug-glug [the under-23 football team]."

Whether they will become the Proteas as well remains to be seen. Quite why the springbok was chosen remains a mystery when South Africa is home to more fierce-some creatures such as lions, cobras, crocodiles and elephants. Springboks can be found in south and south-western Africa and are known for "pronking" – Afrikaan for showing off. The animals appear to bounce on all four legs in a display which experts say is meant to show a predator they are the strong and agile, encouraging them to look at another springbok.

The leaping or jumping added to the Afrikaan term "bok" – which means antelope, deer or goat – gives the animal its name. Visitors to South Africa are often surprised to see the springbok on restaurant menus, usually accompanied by a red berry jus. But while the animal will continue to feature on the nation's menus, it looks set to disappear from rugby shirts. Paul Morgan, editor of Rugby World magazine, said: "I think it would be a great shame to see the springbok disappear – it's right up there with the All Blacks' fern and the Lions as far as brands go. I'm a great believer in history and tradition and the springbok has been with us for 100 years, whether you accept its political history or not. Teams in the northern hemisphere would love a brand like the springbok. The All Blacks, Wallabies, Springboks – they all bring a little something to the game."

But its demise won't just be cultural, said Qondisa Ngwenya, of the sports marketing firmOctagon, in Johannesburg. "I think it will have a huge negative impact on revenue. It was an emotional issue 15 years ago and before, but the minister of sport relented and allowed it to continue since when people have accepted it. If I was advising South African Rugby Union (Saru) or the government I would tell them that we have taken ownership of the symbol and it no longer has political connotations."

Andrew Talliard, 71, is life president of Progress Rugby Club which was formed in the same year that the springbok emblem was adopted by the national rugby team. Until four years ago, the club was a Cape Coloured side, all of whose players were banned from the national team under apartheid.

He said: "I have a Springbok blazer given to me by Saru for my work in rugby over the years, including Sacos (non-racial South African Council on Sport). I think it's a beautiful symbol and a unifying symbol. I don't have a problem with the springbok, despite its past, so we should keep it. I say forgive, but not forget. The Springbok is a part of all of us, whether we like it or not."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks