The Big Question: Have sanctions ever worked, and should they be applied to Zimbabwe?

Why are we asking this now?

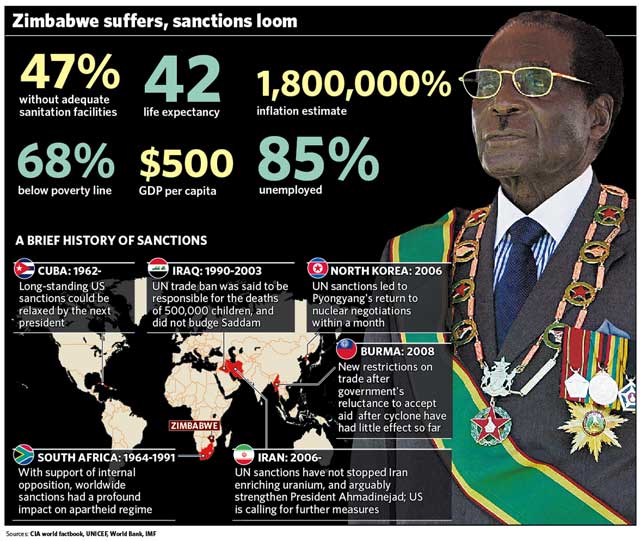

Because the leaders of the G8 richest nations have announced sanctions on Zimbabwe this week in an attempt to end the bloodshed and restore democracy to the country.

What are sanctions?

Restrictions on trade and financial contact imposed upon a state to persuade rulers to change its behaviour – a halfway house between diplomatic disapproval and military intervention. Critics deride them as impotent gestures designed only to quieten the demand that "something must be done" in situations where the truth is that nothing can be done. Sanctions aren't a proper foreign policy so much as a feel-good substitute for one.

Where have they been imposed?

The UN has authorised them to seek compliance with UN resolutions sanctions in Afghanistan, Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, Iraq, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Libya, Rhodesia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, and the former Yugoslavia.

Every US president since 1936 has used them and the Bush administration has threatened or used them on 85 states in the past 12 years including Burma, Cuba, Haiti, North Korea and Syria. Russia is imposing them on many of the newly independent states which were once Soviet republics. Sanctions have been imposed on at least 185 countries since the Second World War.

Have they worked?

Academics say they have in about a third of those cases. They worked in South Africa. Sanctions against Slobodan Milosevic hastened the end of the Bosnian war. They prodded Libya into handing over the two terrorists involved in the Lockerbie airline bombing and then abandoning its ambitions to obtain weapons of mass destruction. Most recently the freezing of $25m in a foreign bank brought North Korean back to talks on ending its nuclear ambitions.

But they have been in place against Cuba for 40 years without bringing down Fidel Castro. Some 13 years of sanctions on Iraq failed to topple Saddam Hussein. After 14 years of US sanctions the military regime remains in Burma. Decades of sanctions on Iran have brought no regime change nor, most recently, persuaded Tehran to abandon its uranium enrichment programme. Yet it depends how you measure success. If a footballer scored a goal every three matches that wouldn't be written off as failure. And, as Iraq has shown, war doesn't inevitably succeed where sanctions have failed, and it's a lot more costly, economically and morally.

How long do they take to work?

Sanctions are no quick fix. When the British colony, Rhodesia, declared unilateral independence the UK imposed sanctions on the minority white regime and the British prime minister, Harold Wilson, predicted the rebel downfall in "weeks not months". It took 12 years, partly because many Western companies secretly ignored them. But the end came when the Rhodesian secret service went to the Rhodesian prime minister and told him the oil would run out in a week.

So why did they work in South Africa?

Because they bit on the business community which, in turn, put increasing pressure on their own government to negotiate with the black majority. Sporting boycotts also increased the psychological isolation of the sport-mad Afrikaaners. But the sanctions were effective because they affected a strong white middle class which could put effective pressure on their own apartheid government.

Why did they fail in Iraq?

Because the comprehensive sanctions there ended up hurting the people they are designed to help. The 13 years of UN sanctions brought poverty and hardship for ordinary Iraqis and almost certainly caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children when water and sanitation systems collapsed and spare parts were unavailable thanks to the sanctions.

An enormous number of innocent people suffered and yet Saddam Hussein was not dislodged from power. Ironically, though, when the West finally concluded that sanctions were not working, the reason, it was claimed, was that they hadn't prevented Saddam from rebuilding his weapons of mass destruction - when. In fact, as we now know, they did achieve that aim.

Can sanctions be counter-productive?

Kofi Annan called sanctions "a blunt and even counter-productive instrument". Sanctions can create a scapegoat for the economic failures of a dictators, as happened with Castro for whom the US blockade of Cuba strengthened nationalistic support. Sanctions also hit the private sector, which shrinks, weakening the political leverage of the middle class and leaving the economy smaller but one over which the regime has greater control.

So what makes for effective sanctions?

Almost everyone has to join in. A country deprived of goods or services by a country can invariably secure them elsewhere. Crafty tyrants like Saddam played on divisions between the US, Britain and France, and China and Russia. China blocks effective sanctions on Sudan over Darfur.

What about 'smart' sanctions?

Over the last decade, following the abysmal failure of sanctions on Iraq, they have become more targeted. Blanket measures which covered food and medicines are out of fashion. In their place have come travel bans on senior officials of a regime, freezes on their overseas assets, the selective ban of key imports, and arms embargoes which weaken a regime's military forces. The idea is to hit the corrupt elite rather than the people they oppress.

This works, to a considerable extent. Some 600 of the supporters of Slobodan Milosevic, then Serbian President, found it impossible to conduct business. Targeted financial sanctions hit top officials in North Korea. But in other cases it doesn't work. Less than £4,000 belonging the Burmese generals has been frozen in all 25 EU member states.

Would they work in Zimbabwe?

General sanctions might not, since the business community and general electorate have no influence on Mugabe. But cutting off his oil might work. Petrol is what supplies the elite and its troops with their mobility. Around 80 per cent of Zimbabwe's oil flows through the line from Mozambique. Cutting that off could immobilise the Mugabe regime.

Will sanctions have any impact on Mugabe's government?

Yes...

* Sanctions helped bring down the apartheid regime in South Africa, and they can do the same in Zimbabwe

* Since an invasion is unlikely, it is the only measure of opprobrium open to the international community

* Cutting off oil could immobilise the military on which Mugabe depends to stay in power

No...

* It will harm the ordinary people of Zimbabwe without seriously affecting Mugabe and his henchmen

* It could increase Mugabe's control further, shrinking the entrepreneurial sector which supports the opposition

* They will take far too long to have a serious impact; they are just gesture politics

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks