The Big Question: What's the history of polygamy, and how serious a problem is it in Africa?

Why are we asking this now?

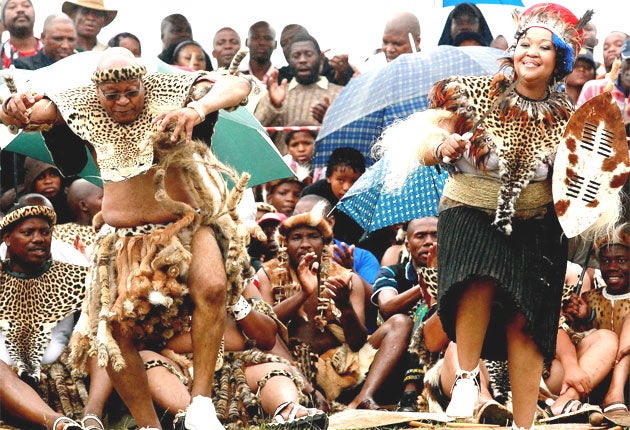

This week, wearing leopard skins and carrying a Zulu shield, South Africa's President, Jacob Zuma, 67, married his fifth wife in a traditional ceremony at his remote homestead in KwaZulu-Natal. His first wife, whom he married in 1973, was there to see him wed a woman 30 years his junior. His second wife stayed home to prepare the reception. He had two other wives but he divorced one in 1998 and another committed suicide in 2000. And he has not finished yet. The other day he paid the traditional dowry for his sixth fiancée.

What's been the reaction to his latest marriage?

Critics say polygamy does not fit the image of a modern society. It sends the wrong message in a country with the world's highest rates of HIV/Aids. And they wonder how he can afford 19 children on a state salary.

But Zuma's respect for tradition is endearing to many rural South Africans. They say it is more honest than hiding his mistresses and illegitimate children like Western politicians. And they say polygamy is a right enshrined in South Africa's constitution.

What exactly is polygamy?

Having more than one husband or wife, though technically when there are more women to one man that is properly called polygyny. When a woman has more than one husband that is polyandry. It takes many forms across the globe. In some cultures one wife is shared by brothers. In others a father and son have a common wife. In others a man has many wives – up to 11 in the Arsi region of Ethiopia. In many a widow is inherited by her dead husband's brothers, father or even a son by another wife.

How common is it?

In 1998 the University of Wisconsin surveyed more than a thousand societies. Of these just 186 were monogamous. Some 453 had occasional polygyny and in 588 more it was quite common. Just four featured polyandry. Some anthropologists believe that polygamy has been the norm through human history. In 2003, New Scientist magazine suggested that, until 10,000 years ago, most children had been sired by comparatively few men. Variations in DNA, it said, showed that the distribution of X chromosomes suggested that a few men seem to have had greater input into the gene pool than the rest. By contrast most women seemed to get to pass on their genes. Humans, like their primate forefathers, it said, were at least "mildly polygynous".

Polygamy is very common in the animist and Muslim communities of West Africa. In Senegal, for example, nearly 47 per cent of marriages are said to feature multiple women. It is relatively high still in many Arab nations; among the Bedouin population of Israel it stands at about 30 per cent. According to The Salt Lake Tribune as many as 10,000 Mormon fundamentalists in 2005 lived in polygamous families.

What are polygamy's origins?

No one knows. But there are clues. It is most common in places where pre-colonial economic activity centred around subsistence farming which requires lots of manpower, Africa being a prime example. High levels of infant mortality may be a factor; when many children do not survive past the age of five a family needs more than one child-bearer to be economically viable.

Then there is war. When a lot of men die, having more than one wife boosts the population most swiftly. The more wives a man had the more military and political alliances he could forge. Wealth and status became wrapped up in the number of wives a man had. A larger family became a source of pride, while a smaller one was a symbol of failure and shame. By contrast, in a society with too few resources and too many people, polyandry is a way of limiting population growth. A woman can only have so many children, no matter how many husbands she has. Such considerations were often consciously political.

Where does politics come in?

Marrying widows was a social strategy for ensuring that orphans were cared for. The Prophet Mohamed, who had a monogamous marriage for 25 years until his first wife died, married many of his other wives – nine in total – because they were war widows. The Koran ordains that a Muslim can marry up to four wives, but only if he can care for them all equally well. Many traditional African societies had a similar custom of widow inheritance to keep the extended family, and its property, together.

Through the centuries other political leaders have seen similar advantage. In Germany in 1650 the parliament at Nüremberg decreed that, because so many men were killed during the Thirty Years' War, every man was allowed to marry up to 10 women. In 2001 President Bashir of Sudan urged men to take more than one wife to increase the population, arguing that it was the huge populations of China and India that had brought them rapid economic development.

Where is polygamy legal?

In South Africa, Egypt, Eritrea, Morocco and Malaysia – and in Iran and Libya (with the written consent of the first wife). In other places – such as Israel, Chechnya and Burma – it is illegal but the law is not enforced.

Is it to do with religion?

In part. Christianity condemns polygamy as an offence against the dignity of marriage, insisting that conjugal love between a man and wife must be mutual and unreserved, undivided and exclusive.

But the Hindu god, Krishna, had 16,108 wives. Many of the senior chaps in the Hebrew scriptures were polygamists including Abraham, Jacob, David and Solomon. And in Confucianism concubines were permitted – but only to furnish an heir not for sexual variety. The Koran also explicitly forbids mut'ah (marriages of pleasure), though many Muslim men ignore that bit.

Why did it start to die out?

Christian missionaries tried to stamp it out in Africa. Some Marxists reckon it was because the system of property ownership it promoted conflicted with European colonial interests. But it was much more to do with a European cultural imperialism. Quite right too, say modern neo-liberals who argue that polygamy in all its forms is a recipe for social structures that ultimately undermine social freedom and democracy. Feminists have not been terribly keen either. A Saudi TV journalist, Nadine al-Bedair, has just caused a huge stir throughout the Arab world by demanding Islamic parity for Muslim women to have four husbands too. The men were not amused.

Is it undergoing a revival?

A little, some anthropologists suggest, as part of Africa's kickback against colonialism. "Europeanisation must not be collapsed into modernity," the new breed of pan-Africanists are arguing, post-modernly. In Israel a former chief rabbi Ovadia Yosef has campaigned for polygamy and the practice of pilegesh (concubinage) to be legalised. There is life in the old ways yet.

Is there anything to say in defence of polygamous marriages?

Yes...

* It's a more honest way of behaving than hiding mistresses and illegitimate children as many men do in Europe and America

* Marrying widows ensures that a society cares for its orphans

* Polygamy is a way for ancient societies to reassert themselves in the face of Western cultural imperialism

No...

* It's completely at odds with the ideal of gender equality that is at the heart of a modern society

* It sends out the wrong message about the transmission of HIV/Aids

* You could argue that a woman having more than one husband is a good strategy for checking the world's population growth

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks