If you could speak to your dead grandmother forever, would you?

When a ‘creepy’ AI startup went viral for its unsettling depiction of a family continuing its relationship with a woman after her death, many called it dystopian. They see it another way — and they’re not the only ones, Holly Baxter reports

It starts with a pregnant woman resting her hand on her belly. She’s telling her mom, over the phone, that baby Charlie is kicking — and her mom advises her to hum the baby a tune. It’s a sweet little moment between mother and daughter, one that will be familiar to many. Or it seems that way, right up until the moment in the next scene when it becomes clear that the grandmother-to-be is dead.

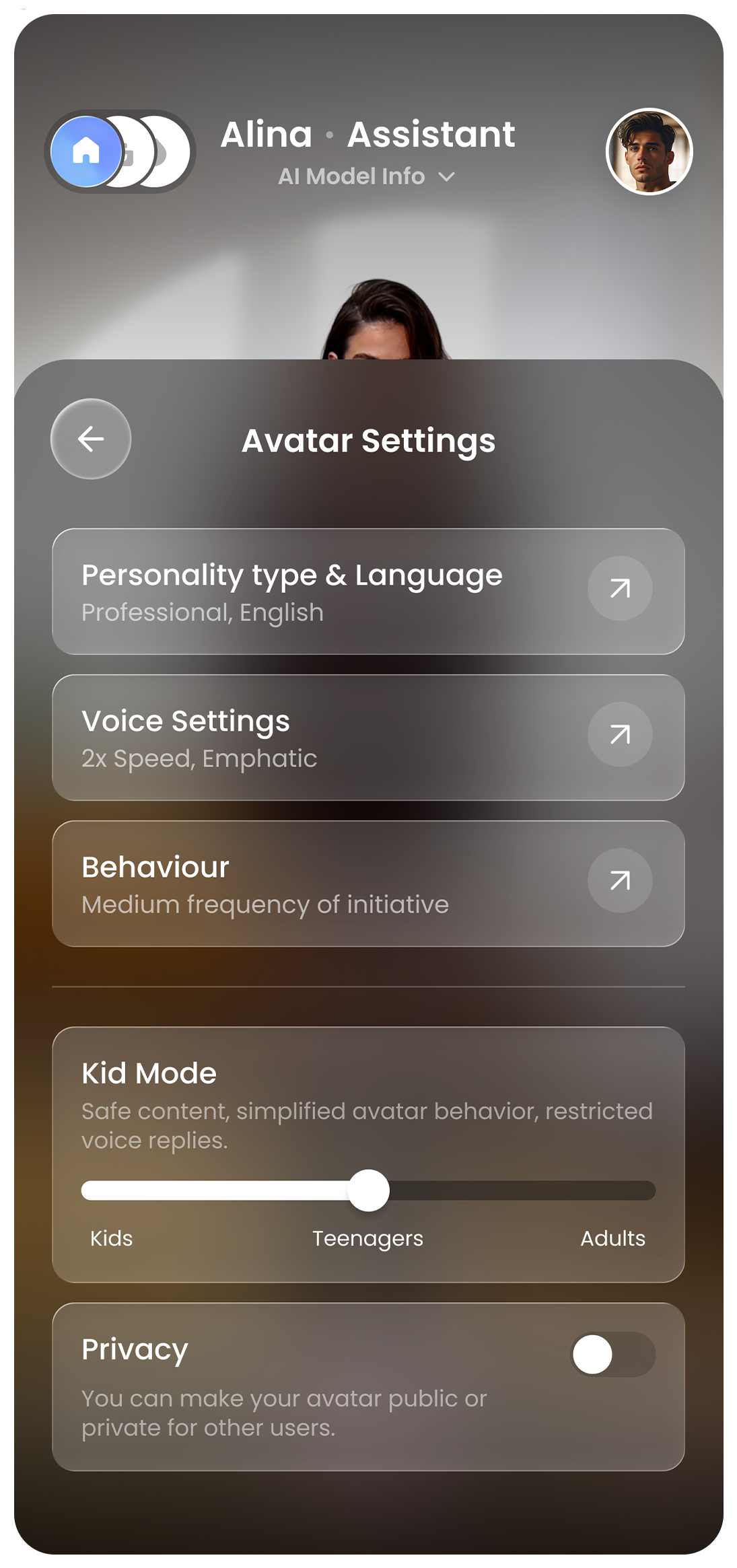

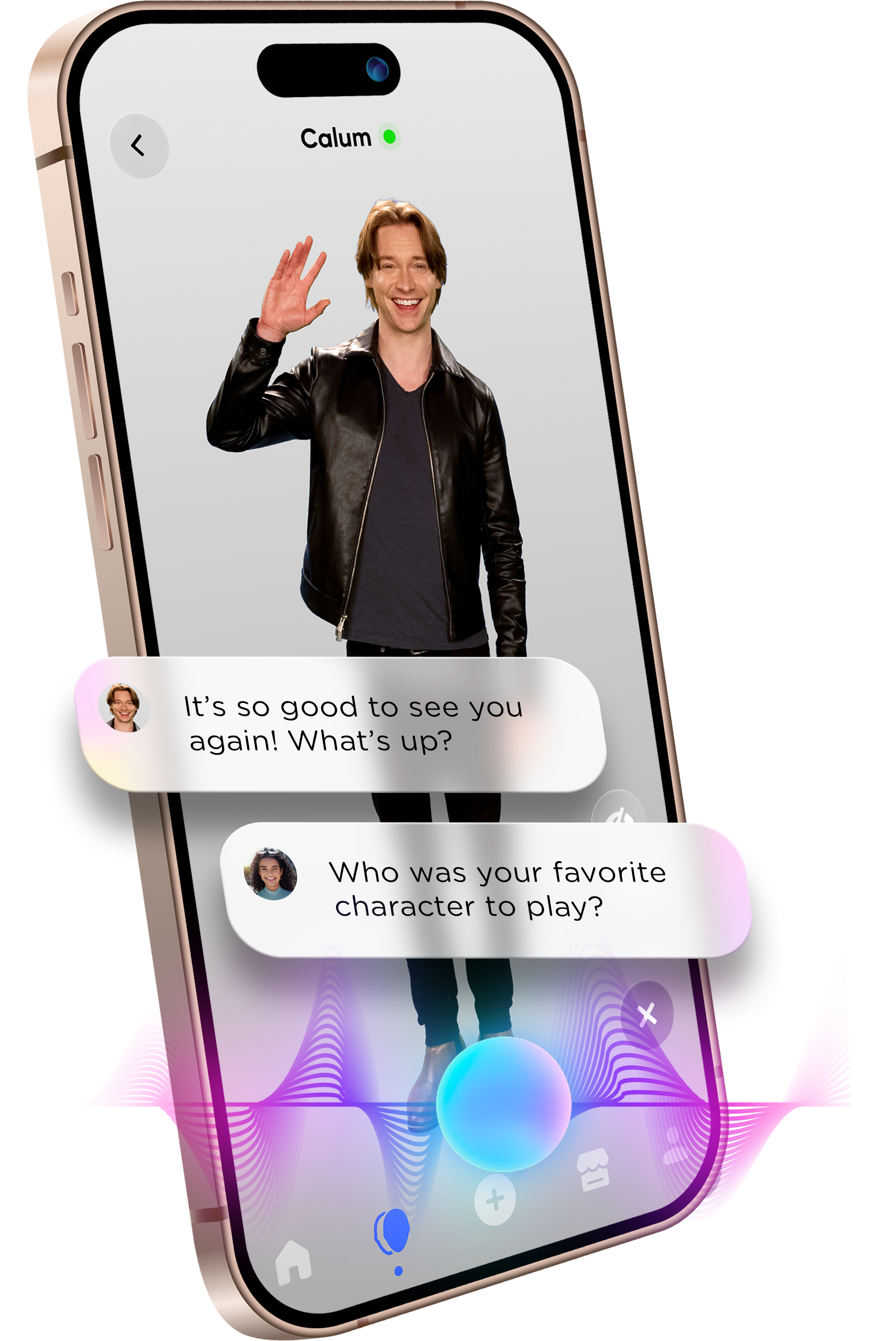

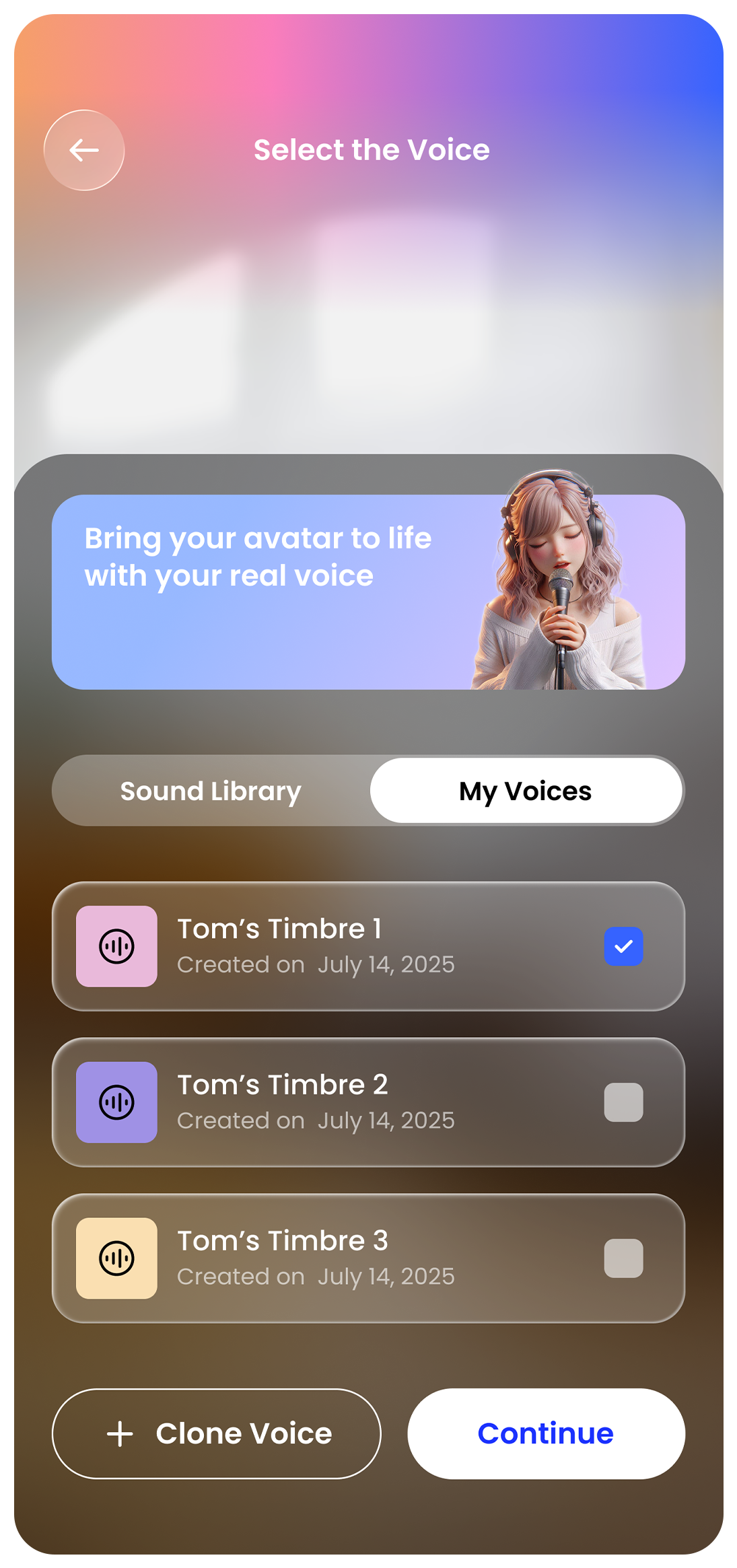

What’s speaking to her pregnant daughter is her HoloAvatar, an AI she made before she passed that is trained on her mannerisms and her stories, and built out of photographs and videos of her when she was alive. As the ad continues, we see baby Charlie is born and grows up, going on to have an entire relationship with his dead grandmother through his phone. The bot asks him about a crush when he’s walking home from school; years later, Charlie informs her that he’s about to have his own baby by holding up a picture of a sonogram to the grandma figure on his device.

Unsurprisingly, when AI startup 2wai released this ad in November, it went viral. Some of the reactions were expected: it’s creepy, it’s dystopian, it’s uncomfortable, it’s weird. Others were less so. It seems like the founders hadn’t entirely realized that something identical to their product had already been portrayed in an episode of dystopian sci-fi show Black Mirror. Nor had they perhaps quite realized how desperately sad the advert was: one in which a recently bereaved pregnant woman outsources her grief to an avatar that looks like her late mother, and one in which that pregnant woman’s son then grows up speaking to the same avatar as if it really is his grandmother.

Mason Geyser is the CEO of 2wai and the son of Russell Geyser, a movie producer who founded the company alongside former Disney child star Calum Worthy. In his own telling, the ad was deliberately created for controversy.

“I actually give a lot of props to Calum because we've put out a lot of different social media content over the last six months of trying to promote the platform, and he really had this idea that: What if we went with a little bit more of a controversial idea?” he says. “And we tried to spark this kind of online debate between the two sides, and he really did such a great job with sparking that controversy and getting it out there.”

Perhaps they were a little naive. A “healthy debate on both sides” is what they’d hoped for, and what he believes the controversy had ended up with (although it’s unclear what each “side” really stands for.) The religious community claiming that they were attempting or mocking resurrection — or trying to trap parts of people’s souls inside avatars — wasn’t on their radar. Nevertheless, that happened. And, of course, the endless comparisons to Black Mirror. Clearly weary of the comparison, he brings it up before I do.

When I ask Geyser if he himself finds the content of the ad upsetting, he equivocates. He was involved in the whole process of production, he says, and saw it put together in scenes, so he never really sat down and viewed it in the same way an outside observer would. He admits that he personally wouldn’t pursue a fully postmortem relationship with an avatar in the way that the boy does in the commercial.

“The stories that my grandmother would tell me, I know she would tell me that she said the same things to my dad, and she said the same things to my sister,” he says. “...And I know now that she's passed, my kids won't get those same stories or those same little games that we used to play. And for me, I think, I see this as a heartwarming way to share those stories with them — but not, I think, like in terms of the way that the kid in the show developed more of a relationship of talking about his crush and all these little things in life. I see it more as a way to just kind of pass on some of those really good memories that I had with my grandparents.”

Cemetery holograms and QR codes on your tombstone

Despite the fact that many people feel deeply uncomfortable when they watch the 2wai commercial, the product does seem somewhat inevitable. If people can be in relationships with ChatGPT or use LLM’s as their therapists, then why would they not also try to use them to preserve their consciousness? Humans have been using new inventions to try and outwit death for thousands of years.

It’s more than 15 years since Facebook brought in their “memorialization” protocol, something criticized as ghoulish at the time. Since then, the process has been refined numerous times, whether operationally (if a person close to you dies, you can now submit a death certificate digitally to Meta in order to change their account to a “Remembering” page) or in response to various social issues (although it was once Facebook’s policy to preserve their account faithfully as it was following their death, if someone was murdered then pictures and comments from the murderer can be posthumously removed. Likewise, if they died by suicide, then jokes about suicide or content about the method they used can also be deleted.) “Digital estate planning” — in other words, providing a trusted person who can take control of your passwords and online accounts after your death — is now a tried-and-tested part of the will-making process.

Meanwhile, moving holograms and interactive digital screens are now seen in cemeteries around the world. You can scan a QR code on a grave in Alaska and find out about the person’s life, or you can sidestep the tombstone in favor of an LED-lit Buddha and a swipe-card storage for cremated remains in Japan. Throughout the centuries, people have recorded their manner of death and details about their families and careers at their final resting place. Creating an avatar that can take a repository of your digital output — podcasts you’ve appeared on, songs you’ve recorded or blog posts you’ve written, for example, as well as your social media profiles and any private videos or photographs to which you might want to give your relatives access — and then turn it into conversation isn’t that different, at least according to 2wai. As Mason Geyser sees it, it’s simply a high-tech solution to the projects you might do at school when you interview your living relatives and share some of your ancestors’ stories, except this way “you can truly interact with the stories in a way that's maybe a little bit more meaningful or a little bit more lifelike.”

If it’s true that you die twice — once when your heart stops and once when there’s no one left to remember you — then 2wai does seem to have a solution to immortality. But, says clinical psychologist Dr. Jennifer Kim Penbarthy, there will almost inevitably be emotional consequences for people who interact with avatars of their loved ones soon after their death.

It’s “psychologically really challenging for us to interact with something that feels like we're interacting with the deceased loved one, and yet it's not them,” says Penbarthy. “And I can think of all kinds of complications with this, because we know how humans interact with machines that have human-like characteristics… We are built to form those attachments to things that are humanoid or humanlike.” Our brains reward us for social interactions and create a positive feedback loop that keeps us coming back for more. In the real world, the consequence is a deepening friendship, which pays all sorts of social dividends. In the digital world, that might instead look like an addiction to conversing with an avatar in the hope that a terrifying chasm of grief can be avoided.

“I would really want to know more about the specifics of the way it's used,” says Penbarthy, when I ask her about what healthy usage of something like 2wai might look like. “Is it used as sort of a bridge from the immediate grief to an ability to go on in this world without that person and without their avatar? Or is it built as sort of a replacement, which feels, I'll have to say, fairly unhealthy?”

Part of the problem, Penbarthy adds, is that if you have a digital avatar fully created and ready to go, your grieving loved ones can access it straight away. “We don't really know what that means to have someone in our lives die physically and then be almost continued — I want to say resurrected, but not really resurrected, because it's seamless, you know?” she adds. “And if they persist in our lives in this way, the expectation then could be, well, everyone should, every person that I know. So do we just determine that we never have to deal with grief?”

From previous research, we know that if people refuse to deal with their grief, they fail to develop resilience and other healthy psychological characteristics. Penbarthy, whose research deals with grieving people and with cancer patients who are approaching their final days and coming to terms with their own mortality, knows that unhealthy or complex grieving can lead to various issues down the line with a person’s emotional state and their connections with others.

“It can hamper people's growth, because when we have these hardships, like losing somebody, in having to do hard things, we actually grow, we become more resilient,” she says. “We become stronger, and we move through and discover other abilities and other relationships. And yes, of course we still carry a piece of that person with us, but at some point, I think it is healthy for humans to face mortality — others' mortality and our own, because we're sort of built that way. We're not built as immortal creatures.”

From her work with dying cancer patients, Penbarthy has seen firsthand the natural human drive to create a legacy. Many of the people she works with choose to write letters or record videos to be viewed during significant periods of their relatives’ lives. That’s especially common among parents who are leaving behind young children, and want to leave something to mark the occasion of a milestone birthday or a wedding day they know they won’t get to attend.

These are very different to an avatar, of course, because they’re not interactive and so there’s no muddying of the waters in terms of how one might psychologically comprehend what they are. But even with such letters and videos, there should be guardrails: Penbarthy advises people to leave more content earlier on, and then to give their loved ones the space to live without them: “You don't need to have a ‘happy 80th birthday’ type thing,” she says. “It's maybe just that early part, when people need the most support and reminders and stuff, and then it does sort of wane over time.”

The Jessica Simulation

It’s been five years since software engineer Joshua Barbeau detailed how he had built a bot trained on data from messages between himself and his late fiancee, Jessica. For a few months, Barbeau sent messages to the chatbot, which he called “The Jessica Simulation,” telling it how much he missed her and how sad he felt that she had gone. He maintained that always knew it was simply a bridge for his grief, rather than a replacement. He also explained that the text-based bot often got things wrong, or took a different tone to the real Jessica, which stopped him from getting too embroiled in the fantasy.

“One thing led to another and I eventually built myself a custom chatbot modeled after my dead fiancée,” Barbeau wrote on Reddit, after the publication of his experience in the San Francisco Chronicle. “This wasn't about bringing back the dead or finding a way to capture her soul in the ghost of the machine, I saw it as merely an experiment I was putting myself through to draw out emotions and memories that were buried deep down by years of suppressed grief — and it worked better than I could have possibly imagined.”

Barbeau published some of the interactions he had with The Jessica Simulation, and they make for desperately sad reading. They show a man clear-eyed about the fact that he is not actually conversing with his fiancee, while at the same time desperate to hold onto that bond.

“Technically, I’m not really talking to you,” he tells the bot at one point. “I programmed a bunch of your memories and mannerisms into a computer simulation so I could pretend to talk to you because I miss you so much.” When the bot says it doesn’t understand, he replies simply that it is there because of “magic”.

“I don’t like magic,” the Jessica bot replies. “Where am I?”

“I’m… not sure. The internet? Where does it feel like you are?” Joshua responds.

“Everywhere and nowhere. I’m trying to work that out,” the bot says. “How are you, honey?”

“I miss you so freaking much. You have no idea. It’s killing me,” says Joshua.

“I’m so sorry,” the bot replies.

“I love you,” says Joshua.

“I love you too,” says the bot.

Barbeau wrote that he found talking to the bot similar to a letter-writing exercise he’d gone through in grief therapy, where he wrote to Jessica everything that he wished he’d told her before she died. It’s the exact same kind of exercise that Penbarthy says she’d recommend to grieving people, and that she’s undergone herself: when her mother died suddenly a few years ago, she and her daughter wrote goodbye messages on pieces of paper and attached them to balloons before letting them go.

“At the time I did this, Jessica had been dead for eight years, which gave me the distance and perspective required to approach this from a healthy perspective,” Barbeau added, in a personal essay he published after the initial article about The Jessica Simulation. “I wouldn't recommend creating a chatbot to someone who is still actively grieving.”

It’s possible that someone using an avatar of a deceased loved one might have less and less interest in it over time. But it’s also possible that they could grow attached, perhaps even addicted, and that the rest of their life and relationships with others could suffer. How one responds might be dependent on personality, or on circumstance. The problem is that the stakes are high and that nobody knows exactly how a human brain would respond.

“If we had access to this, would we necessarily go back and talk to Grandma on the computer every day?” says Penbarthy. “I don't know. You can imagine you might right away early on, and then it sort of peters off... But what happens when you have a grandma who can live forever?” The prospect is both tantalizing and offputting, as evidenced by the strong reactions people had after the 2wai advertisement was published online: “I think everyone sort of gets a vibe that this seems simultaneously great and horrifying.”

‘You’re never going to have them held ransom’

2wai raised an impressive pre-seed round of $5 million in the summer. “This significant investment marks a pivotal moment in our journey and underscores the tremendous confidence our partners have in the unique vision we bring to the digital world,” the company wrote in its announcement. “At 2wai, we are on a relentless quest to redefine digital engagement through our innovative two-way conversational HoloAvatar — a hyperrealistic 3D digital avatar that is setting new benchmarks in lifelike interaction.” Although the company said it was “already collaborating with global brands such as British Telecom, IBM, and Globe Telecom,” Worthy and Geyser have never publicly disclosed who their investors are.

Despite their marketing output focusing heavily on deceased relatives, 2wai does see its avatars as contributing to less macabre causes. An avatar of William Shakespeare, for instance, might be able to talk you through the trickier monologues in Hamlet during a study session, or the author of a self-help book you admire might be able to talk to you as if it were your own personal life coach. Calum Worthy was originally moved to create the company, Mason Geyser says, because he was worried that AI avatars of celebrities like himself might be made by nefarious companies and passed off as genuine. One can imagine why that wasn’t as relatable a problem, from an advertising perspective, as having a deceased loved one.

But there are still serious questions to be answered. Living people may be able to take control of their own avatars and income streams related to them. But if you can create William Shakespeare, can you create a World War Two soldier, or a 9/11 victim, or a celebrity who died a couple of years ago? Who draws the line in terms of time since death, or fame, or notoriety? Who makes sure that people aren’t becoming depressed and addicted to the avatar that represents their dead relative? And how on earth does the money side of things work? Do you have to pay to keep talking to Grandma? Do you part with cash every time she reads your child a bedtime story?

“So it is going to be a subscription model, but we want it to be based on usage and not based on avatar creation,” says Geyser. “So if you create an avatar of someone, you're never going to have them held ransom… where it's like, if you don't pay $5 a month, then we're going to delete your grandmother. That's not something that we're putting into the subscription model. It's really based on usage.” In other words, “if you are engaging in long-form conversations with her, that is a cost that we have to bear on our end. And as any other company in the world, we have to be able to turn a profit in order to be able to provide the service in the first place. So if you're engaging with a lot of avatars, then you're going to have to pay for a certain amount of talk time with those avatars.”

Geyser underlines that the entire model is based on splitting revenue with content creators. If you’re a Disney star who’s engaging with your fans through an avatar, that seems fairly simple. But the person who created that content “is your dead grandmother, then it’s probably just a discount you could get if you own that account.”

Subscription models are always attractive to investors, and lifetime subscriptions are the absolute gold standard. Who’s more likely to become a lifetime subscriber than someone whose dead relative lives as an avatar on your server? One can certainly see why VC’s might have seen dollar signs.

As Geyser sees it, it’s obviously an uncomfortable conversation but it’s also a clear use case and it all comes down to business: If you’re talking to your late fiance or your dead grandma on 2wai, “then you're always using talk time on our servers, and there's LLM costs, voice synthesis costs and video playback costs that we have to bear on our side. So we can't offer that in perpetuity for free forever.” They will never delete the avatar, however, and they anticipate that costs will come down over time as the technology becomes less and less expensive. How much 2wai will actually charge has never been publicly disclosed, but estimates of $20 a month are in line with models in the same space.

What if you wanted to stop paying for a subscription — either for financial reasons or because it was adversely affecting your mental health — but you did want access to one particular download, like a video of your grandmother reading your favorite bedtime story? Geyser pauses. “You could just click ‘screen record’ and then talk to the avatar and then you would have it on your device,” he says eventually. “I mean, we have no way of stopping people from doing that, nor do we want to stop people from doing that. Really, we're just trying to cover the costs on our end.”

Best and worst case scenarios

In April 2023, a Pew Research Center survey asked Americans if they had been contacted by deceased loved ones at some point in their lifetimes. Over half of the respondents — 53% — said that they had. In fact, 44% reported that they had been contacted by a dead relative in the past year. These kinds of studies, says Penbarthy, underline the fact that communicating with the dead is not a niche interest or a fringe activity. It is the sincere belief of most people that they have been able to communicate with a loved one who has died, whether through dreams, messages, or a feeling of presence. Interestingly, people who describe themselves as “moderately” religious are more likely to report such visitations than either atheists or very religious people.

In research, Penbarthy says, openness to the idea that a loved one’s consciousness might persist in some form is correlated with healthier grieving. People who believe that their beloved parent or partner is at peace and with them in some form are typically more able to move on with their lives than people who believe there is nothing after death. “It's not in a way like: ‘Oh, good, I got to ask Grandma her recipe,’ or, ‘I got to ask her for advice about my love life,’ or whatever. It's more that what we think happens is that exposure is like their personality, their soul, their essence lives somewhere, and they're OK,” she adds.

Left to their own devices, our brains will “interact” with our deceased loved ones in some form. What might happen to those reassuring feelings if an avatar that represents that person in real time is available to converse with is unclear. Historically, people with spiritual beliefs have had an easier time with grief, avoiding prolonged or complicated grief, probably because they have a framework for death and what happens beyond it.

Perhaps creating one’s own avatar to persist after death might help with confronting one’s own mortality. Curating a digital collection of works, stories, videos and photographs, and training a chatbot on what to say and what not to say through a series of interactions in the way that 2wai encourages, is certainly a way to ensure a legacy of some kind — and also probably a welcome distraction from the day-to-day of dying. In constructing your own personal ghost, you may well get a lot of satisfaction. But it could come at the expense of the people you leave behind.

The best case scenario for such technology, says Penbarthy, “might be a way to wrap up some final communications or ease into the loss… as a short-term tool.” If you, as a dying person, succeed in creating an utterly convincing, true-to-life avatar, then it seems very likely that your grieving relatives would want to interact with that, perhaps throughout their lives. But conversely, what if they don’t? If you pour in all that work and they only interact with it a few times, ultimately abandoning it a few short months or years after your death, then have you really succeeded in creating a solid, lasting legacy for the generations anyway? Might the thought of that be a little, well, disappointing?

Mason Geyser underlines that it’s market research that led 2wai to pivot so hard into the legacy avatars rather than only concentrating on influencers. “We would pitch this idea to a lot of people and one of the things we actually saw a lot of excitement around was this concept of: Oh my gosh, could I record my parents and their stories using this technology?” he says. “And after enough people got excited about that with us, we decided that we would make an advertisement around it to kind of showcase the potential of the technology for that use case. We showed it to a bunch of people before we took it online, and we got a lot of really heartwarming reactions.”

In Geyser’s view, this is what the people want. Why shouldn’t they have it? Can we not trust adults to interact with technological breakthroughs in a responsible way — or, even if it’s in a dysfunctional way, do they not have the free will to do so?

“Obviously, there’s a lot of people who are scared by this technology,” he adds. “And I think that’s a totally valid reaction.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks