Formerly incarcerated exec says past allies Biden and Boris ‘failed’ on criminal justice

Ashish Prashar, an executive and former ally of Joe Biden and Boris Johnson, tells Josh Marcus both leaders have kept their countries on a path towards mass incarceration and racism.

With so much focus on crucial issues like Covid, the climate crisis, and the invasion of Ukraine, it can be easy to forget that President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Boris Johnson have presided over impactful developments in the criminal justice system.

Both leaders have kept their respective countries on the decades-long track of continued mass incarceration. Ashish Prashar has a unique insight into these men, and how the US and UK could better serve those going through the justice system.

As a teen, during a troubled period in his life, he was arrested for theft at a London department store and sent to Feltham Young Offender Institution, one of England’s most notorious prisons. After surviving his time there, he went on to an unlikely career in journalism and politics, working for figures like Tony Blair, Boris Johnson, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden.

Now, he’s an executive in New York at creative agency R/GA, and says leaders on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as big businesses, have failed to give kids with a background like his a real shot at redemption.

The Independent sat down with Mr Prashar to get his take on Boris, Biden, and how to reintegrate formerly incarcerated people in a meaningful way. (This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

How would you rate Boris Johnson’s policies on criminal justice during his time as PM, especially during the pandemic?

The UK is a decade behind the US on criminal justice.

Boris spent the pandemic building prisons, and people supported it left and right. People are OK with detention without trial. These are not good things. Just because the UK’s criminal justice system is smaller, doesn’t mean it’s not draconian.

He pledged to spend £2.5bn building 10,000 additional prison places and expand random stop-and-search. More than half the young people in jail are Black and brown. Black people are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched. The inevitable conclusion there is that it’s a racist policy to target Black and brown people.

It’s the same mass incarceration model as the US. It’s probably more polite. That’s really what it is.

You were once an ally of Johnson’s, working as his press secretary when he was Mayor of London. Why work with him back then, and what changed?

I needed to do this to get my own privilege. It was giving me distance from my record to do whatever else I wanted to do in my life. I made a deal with the devil I guess. I worked on his campaign in 2012. I helped run a programme for 1,000 formerly incarcerated young Black and brown boys, where they would return to education and job training.

It wasn’t great. The systems, we didn’t really have the civil service support. A lot of it was beg, borrow and steal, and working with local organisations who were helping people, calling companies.

The ending of that programme made me realise it’s all a gimmick with Boris. It was good because he thought he’d get Black votes or brown votes with that gimmick. I’ve always known he’s a p****k and a w****r, but the problem is, 1,000 young boys wouldn’t have had that programme otherwise. That’s better than nothing. You have to work with people you don’t necessarily like to get things done in this world.

Has the Black Lives Matter movement created any new momentum around policing and criminal justice reform in the UK, compared to the US?

I think here in the US, it has a real direct, connection. Slavery. The 13th Amendment. There’s a real direct correlation here that’s very visible to people. I think white people in the UK don’t see that connection. There’s a weird love for the police, that’s even weirder than in the US. They have softer branding, police TV shows. With their lack of guns, that doesn’t mean police violence doesn’t happen in the UK, there are just different tools. We don’t report on tasers the way we do shootings.

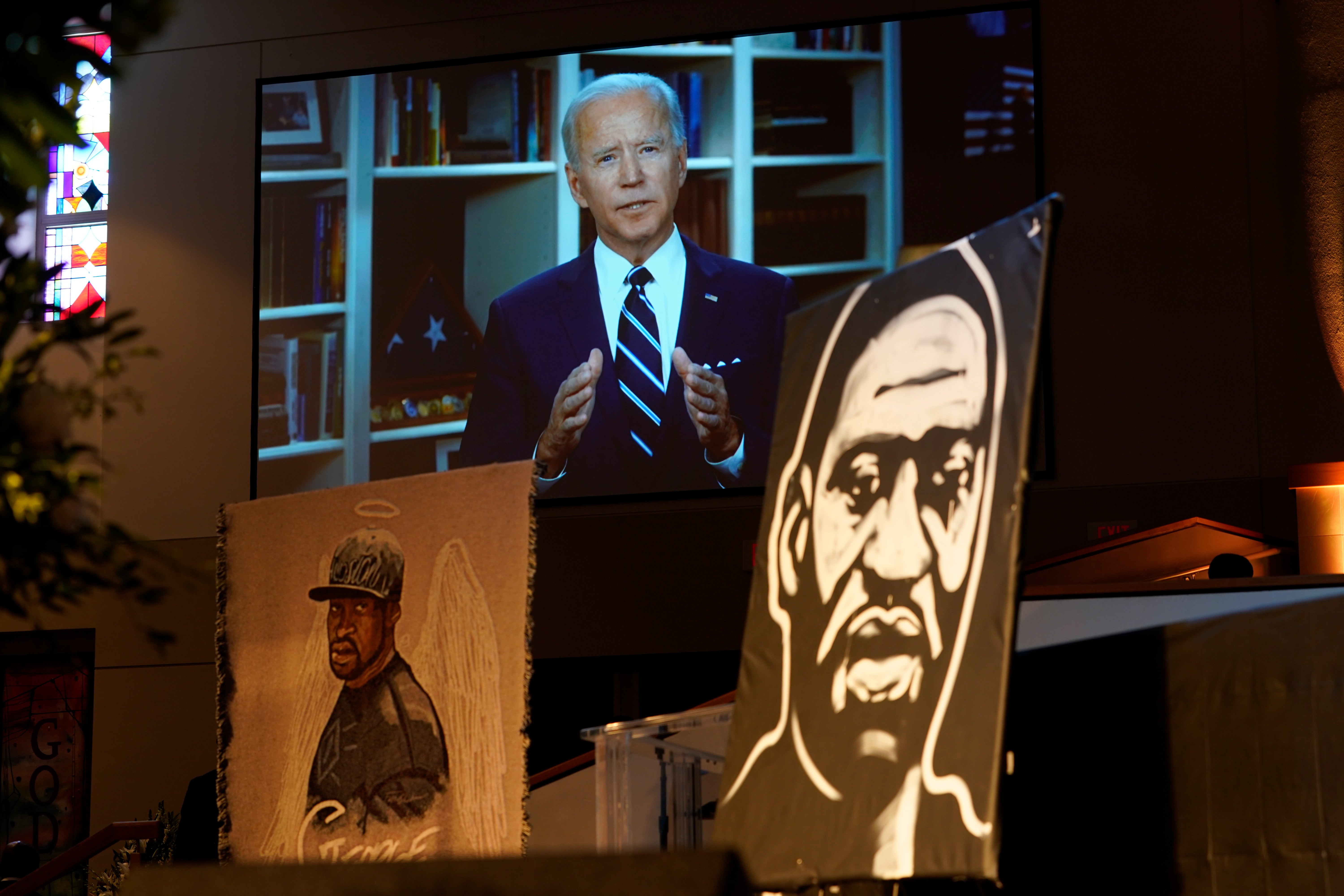

What about Joe Biden, who you helped elect in 2020? He made a number of striking criminal justice pledges on the campaign trail and in the White House—ending the death penalty, tackling police racism in the name of George Floyd. Has he followed through?

He has done nothing since being in office to address criminal justice reform. Has failed us all so far. The joke of it all is that he thinks this is going to win him an election, being tough on these things, when he forgets the people who support reform are the very people who helped him win these elections: massive Black populations in cities in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Georgia.

As vice-president, he often talked about compassion. I often think about a speech he gave at Yale in 2015, where he said, “It’s not all that difficult, folks, to be compassionate when you’ve been the beneficiary of compassion in your lowest moments.” Joe Biden and many other politicians around him don’t show that same compassion to people impacted by the criminal justice system in our criminal legal system.

He has the power to show humanity and compassion in this moment to so many people in prison. It took them nearly a year to certify the CARES Act after the beginning of the pandemic and begin releasing a whole bunch of people in prison. It took a year of lobbying to get him and his Justice Department, especially Attorney General Merrick Garland, to say yes to keeping them at home.

He promised to end the death penalty. He could do that right now by commuting people’s sentences. He can do all of that without Congress. He’s the author of the modern prison-industrial complex. Did he ever change?

Switching gears, what was it like being in Feltham as a teenager, and how did that impact your life going forward?

It was an out of body experience. All I saw were children. They’re all kids. We’re talking about 15, 16, 17 years old. People forget they are still developing.

There were beatings, guards berating people, racist taunts. They were trying to goad us into fighting them. I was put into solitary confinement for my safety. The environment was just made to make us suffer. The goal is to make us a prisoner even we’re out.

Once you got out, what sort of support and rehabilitation services did you get?

I got 46 pounds and told to jog on. There was no real support. There was no real re-entry programme. It was 2001, right at the end of the Tough on Crime era. You didn’t have that same momentum as we have now to transform that environment.

One day, Mr Prashar’s grandfather, who ran a corner shop, introduced him to a former editor of The Sun and News of the World during a book launch for author Donald James. The editor helped Mr Prashar find work in the newspaper industry. He used that platform to transition to doing communications for members of the Conservative Party.

Was it hard breaking into politics with your background?

[The editor] saw my life experience, all of it, as a positive. Most importantly, he saw me as a person. I felt like there was a degree of protection there. I can’t speak to what they actually thought under the surface. I know that I was lucky that I was acquiring privilege. How many people in politics came out in the time I came out and had a criminal record?

I’ll tell you what, even some of the companies I work with today wouldn’t have employed me. They’re all progressive now and say a lot of sh**. Even today, they struggle to hire formerly incarcerated people. Agencies, all these guys who have all these progressive values, wouldn’t hire me, a 19, 20-year-old with no life experience they feel is valuable.

You’ve advocated for strategies like second-chance hiring, and New York’s proposed Clean Slate bill to reduce the harms of mass incarceration. Why are these policies, which seek to make it easier for formerly incarcerated people to expunge old convictions, find work, and access government services, a priority for you?

Having a prior arrest or conviction can cause a half a million dollars of lost income over a lifetime. The loss of potential earnings has larger economic consequence for our society. This is a moral thing and a justice thing, but there’s an economic argument there too. It hurts communities. It hurts businesses.

It makes sense for our whole community, our country. We’re talking about a labour shortage right now. We’re talking about the economy not being able to bounce back. Are we really helping the economy, or proactively taking a knife to it? Clean slate is an anti-poverty bill, a jobs bill, a public safety bill all in one.

Has the tone changed in recent years, when it comes to businesses and others discussing justice reforms?

The pandemic helped. More people are connected to these issues and have taken time to learn about them.

70 million people in America, adults have a record. That’s a third of our working population. That is an indication that by chance or by association you probably know someone impacted. They might not have told you. These are things that we keep secret for so long.

More and more people want to do this work. Even if executives don’t want to do it, their people want to do it. It’s not just coming from customers. It’s coming from their own staff. They won’t work for you if you don’t care.

If we’re talking about Black lives mattering, there is no reason we shouldn’t be encouraging changes to that system that has impacted so many of our brothers and sisters. Business leaders know so many of their staff are connected to this, now more than ever.

Ashish Prashar is on the advisory council of the Responsible Business Initiative for Justice, the organiser of the American Workforce and Justice Summit 2022 , a two-day gathering of more than 150 business leaders, policy experts and campaign organizations focused on how corporations can meaningfully engage in justice issues and create change in the workplace and beyond. AWJ 2022 will take place in Atlanta, Georgia, on 4 and 5 May. The Independent will be reporting from AWJ 2022 as media partner.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks