What Brazil's billionaires show about the extent and reach of wealth in a troubled country

This year, Brazil should be celebrating its world-power status. Instead its Olympics are in jeopardy, and the country is mired in corruption and endemic inequality – Alex Cuadros, the world’s first-ever ‘billionaire correspondent’ (for Bloomberg News), arrived in 2010 and spent five years there

Miami is popular with ultra-rich Brazilians, a major private banking hub. And while private bankers tend to avoid press, having Bloomberg on my business card opened doors. Some considered me a fellow traveller in the world of wealth, I sensed. Others probably just wanted intel. On my first trip to Miami, I met Santiago Ulloa, a Spaniard who works for several rich families from Latin America. Santiago spoke in heavily accented English and listened with a smile that conveyed goodwill and calm. He dressed immaculately, in a well-tailored navy blue suit, crisp tie, and fashionable rimmed glasses. We drank espresso at a table overlooking shining new office buildings, vacant for years in the wake of the crash but now filling up again. Santiago runs a “multifamily office.” His job is to help families of UHNW – I had to learn acronyms like this: ultra-high-net-worth – maintain their money from generation to generation.

“The biggest thing that upsets these people is if money is going to be good or bad for their kids,” Santiago told me. He gives his clients a deck of cards entitled “Keeps Me Up at Night”, which works as a brainstorming exercise for family patriarchs who need help giving voice to their concerns. Each card carries a theme like “Trust” or “Second Home” and questions like “How will the age difference between me and my spouse affect my wealth planning?” or “How can I make sure that my values live on after I’m gone?” He also arranges kidnapping insurance and prenup lawyers, and hooks his clients up with the best investment people, too.

Calculating someone’s net worth, I learned, involves a mixture of reporting, maths, intuition, and unwritten tradition. It means digging through securities filings, learning to read a balance sheet, and interviewing analysts who know how to put a dollar value on opaque assets. For the rich, the problem becomes taking care of your stuff. With $100m (£68m), you might have bodyguards, assistants and a permanent staff to care for your homes. With $1bn , you need someone like Santiago. With a few billion, you need a family office of your own, a whole company to manage your assets and affairs – and sometimes that’s not even enough. I met a woman called Natasha Pearl who tends to the trickier aspects of their lives. She knows who to call if you want to buy a racehorse or sell a diamond necklace. She knows discreet psychiatrists for troubled heirs and heiresses. She can ensure that every one of a billionaire’s homes stocks the exact same outfits, so he never has to pack much when travelling.

Exploring this world, every time I thought I’d seen the peak of luxury, I discovered a higher level. I used to feel special because I flew around in business class. One day I got bumped up to first class, and business struck me as almost proletarian. Then in São Paulo I visited an “executive aviation” fair, where large-bellied executives sipped champagne and smoked cigars among helicopters, jets and scantily clad promo girls. I walked into a 100ft Bombardier Global 6000, which cost $50m and could fly from São Paulo to Paris without refuelling. The interior was spacious in a way airplanes aren’t supposed to be. Wide cushiony seats lined one side; toward the back was a double bed. The bathroom had a shower and a leather-covered toilet, wide and throne-like.

Once I took a date to D.O.M., the best restaurant in São Paulo, or at least the priciest. We both ordered the tasting menu and the “wine harmonisation”. Over three and a half hours, we consumed ten small dishes, each of whose artfully clashing ingredients was explained to us in minute detail. One course was just two ants plucked from the deepest Amazonian jungle. Served raw, they tasted like citrusy flowers; I needed a gulp of wine to wash down their prickly legs. Inevitably the bill had to arrive. Even though I told myself this was research, I was spending my own money and I felt kind of dirty dropping 1,889.52 reais – nearly $1000 then – on dinner for two. That was three times Brazil’s monthly minimum wage. I looked around the dim, hushed room, and if anyone else had a heavy conscience, their faces didn’t show it. At one table all six guests played with their iPhones, as if to broadcast that eating at D.O.M. was banal to them by now. And they were probably just millionaires. (It wasn’t long before I heard myself using the word “just” like this.)

On a trip to Rio, I asked a luxury estate agent to show me his finest property. We met in front of a nondescript six-storey building on Ipanema beach and took the elevator to the penthouse, a 6500sq ft duplex. The owner was away, but the butler, let us in. (A beach butler, he wore shorts.) From low-slung modernist chairs in the high-ceilinged living room, we beheld the panoramic sea. In the master bedroom, the butler pressed a panic button, and metal shutters lowered over the doors and bulletproof windows. The butler led us into a sitting room with wavy bands of bright colour emblazoned on the walls, which struck me as tacky and garish after the understated elegance of everything else. But he told me to look closer. Leaning in, I could see that each stripe was made from the wings of thousands of exotic butterflies.

I was coming to grasp what it means to be a billionaire, at least in material terms. It’s a lot different from having a 100 million. With that, you can’t buy a $50m jet, a $40m penthouse and a $20m yacht – you have to choose one. With a billion, not only can you have all these things but they’re sensible investments. When the waiting list for new jets grows, used ones can rise in value. And as the population of billionaires expands, so the price of super-luxury apartments climbs, regardless of what’s happening in the economy of the masses.

Again, between a 10-digit and 11-digit billionaire there is an order of magnitude. At those reaches, it’s impossible to spend all your money on beachfront villas and super-yachts and such toys. That’s when you get into vanity projects – though you can burn through far more with philanthropy. And in the ladder of luxuries, art occupies a rung up near philanthropy.

Purchasing art confers a patina of status and culture for money made in un-sexy sectors like cement or packaged foods. Anyone with a little bit of money can buy a Louis Vuitton handbag. Very few can buy the new Jeff Koons, even if they do have the tens of millions required. But art is an investment too, a must in any billionaire’s portfolio.

The art industry noticed the rise of the Latin rich early on. In 2002 the people behind Art Basel in Switzerland started an offshoot in Miami. For a week each December, Miami Basel fills the half-million-square-foot Miami Beach Convention Center with a few billion dollars’ worth of paintings, photos and found objects cleverly arranged. The fair is open to the public, but serious buyers attend the day before the general opening. Even among the VIPs, though, there are gradations of very importance. The lowest level of VIPs can attend the vernissage from 6pm to 9pm on the eve of the general launch. There’s a more exclusive showing from 3pm to 6pm, and before that you have something called First Choice.

To call your VIP lounge by its name would be crass, so the fair had a Collectors’ Lounge. Crates of Miami Basel’s official champagne were arrayed in an arc at one side. Past the bar I could see a booth for NetJets, the private-plane time-share company. Toward the back of the lounge was another, smaller lounge administered by UBS, the Swiss bank. You could only enter with some higher-level credential I hadn’t heard of. The fair was organised like Russian nesting dolls of exclusivity.

Miami was a little utopia for the new rich of Brazil, but some of the richest Brazilians wouldn’t be caught dead there. The country’s top art buyer, Bernardo Paz, never attends Miami Basel; he sends an emissary. He built the world’s largest open-air art museum, Inhotim, on a 240-acre estate he owns in south-eastern Brazil, but he feels no affinity with his fellow billionaires. He once called them bundas-moles – soft-arses – who don’t get Inhotim like its working-class visitors do.

Though his money was new, Paz’s discretion placed him in an older tradition of wealth. He made his fortune quietly, over the course of many years, mining iron ore. Few had heard of him until Inhotim opened its doors in 2006. He poured $70m into the place each year but was still nowhere to be found on the Forbes 100. The number of Brazilians on the list had jumped from six in 2002 to 36 a decade later, and yet there were plenty of billionaires Forbes hadn’t found.

My editors gave these people the fancy name “hidden billionaires” and told me to dig them up. Unlike most of the Brazilians on the list, they usually ran private companies that didn’t release any financial information. They gave few interviews. They might own half of Miami, but they didn’t publicise it. I felt at first like I was looking for leprechauns.

One of my editors gave me a tip. Visiting São Paulo, he took me to dinner at the rooftop restaurant of Hotel Unique, which looks like a giant watermelon slice of polished stone. “Who owns this building, anyway?” he asked me. I had no idea. So I dug a bit. Turns out a guy named Jonas Siaulys owns it. Jonas’s late father helped found Brazil’s largest pharmaceuticals maker, Aché. I’d bought Aché’s ibuprofen tons of times without absorbing the brand name or wondering who might be behind it. And Aché products filled the shelves of the Pague Menos pharmacy near my house. Pague Menos, I learned, is Brazil’s largest pharmacy chain. It belongs to a guy named Francisco Deusmar de Queirós. Jonas might be a billionaire; Deusmar definitely was.

Suddenly, billionaires seemed to be everywhere. I couldn’t believe how many ultra-rich people lurked all around. For someone hunting billionaires as if they were rare animals, it brought a kind of gold-rush feeling. At times it was exhausting. Arriving at my apartment one day, I paused before shutting the door. On the lock’s strike plate, I could read the name La Fonte – another company owned by the Jereissati. Even at the bar I couldn’t get away from them. I drank

Brahma beer made by Anheuser-Busch InBev, a company controlled by three well-known Forbes listers, Jorge Paulo Lemann, Marcel Telles, and Carlos Alberto Sicupira. But what about beers like Itaipava and Devassa? The first brand belonged to Walter Faria, the second to the Schincariol brothers – some of the first hidden billionaires I uncovered. It wasn’t long before billionaires started showing up in my dreams.

Eventually I looked beyond consumer brands. In a downtown subway station, a plaque announced the contractor who had laid the line: Camargo Corrêa. In Rio I’d seen a building that resembles Rubik’s cubes arranged in Jenga stacks mid-play. It’s the headquarters of Petrobras, the state oil company, but was built by the private company Odebrecht. Camargo and Odebrecht both were family-owned – and huge, raking in many billions in revenues each year. I realised I was looking at two of Brazil’s richest families. They were nowhere on the Forbes list. And that’s how they liked it. They didn’t want to draw attention to themselves. And soon I would realise this wasn’t just press-shyness. Behind their fortunes lay a dark history...

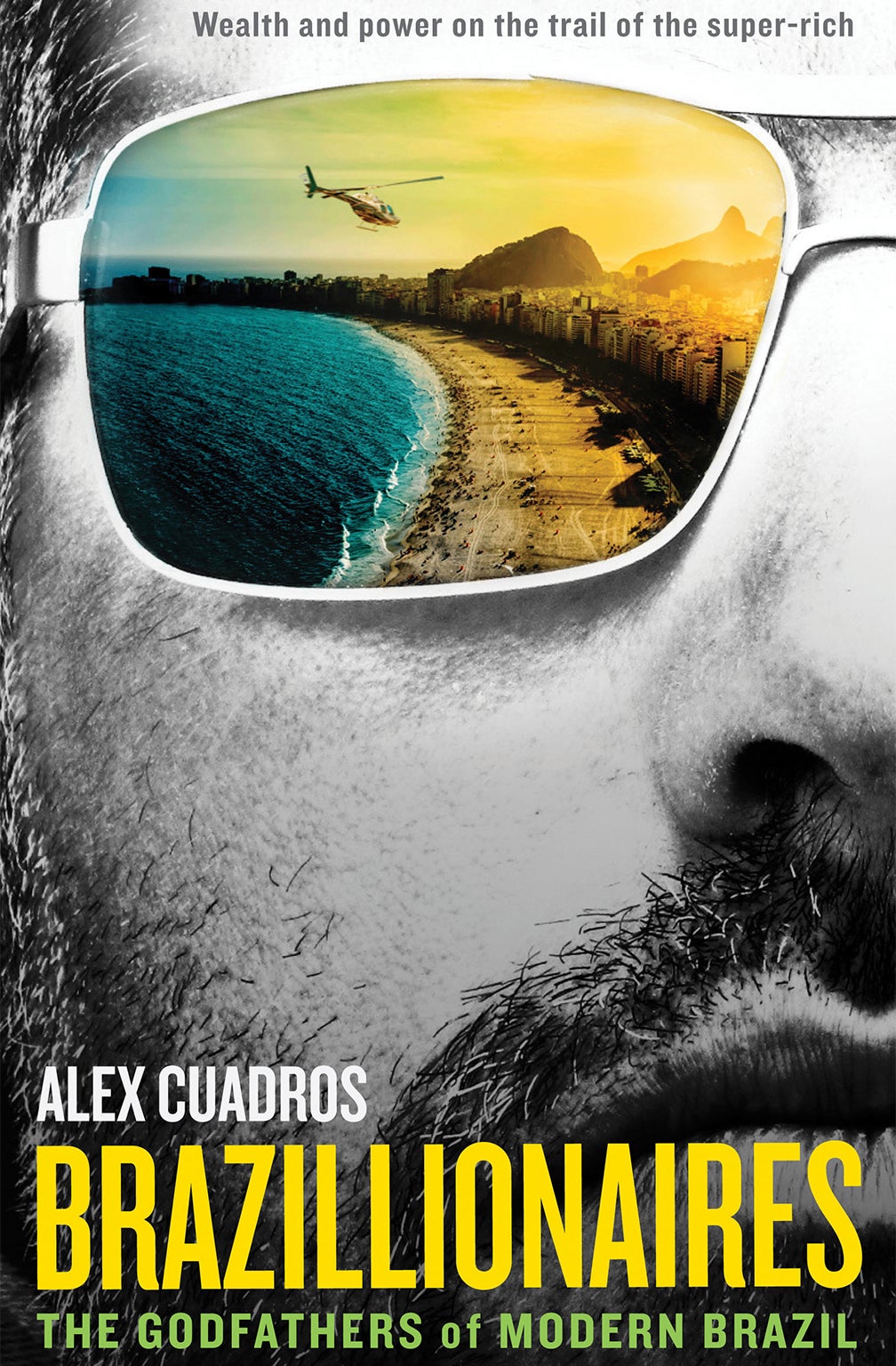

This is an edited extract from 'Brazillionaires: The Godfathers of Modern Brazil' by Alex Cuadros (Profile, £10.99), published tomorrow

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments