Bush the father, by Bush the son, adds context but offers few real insights

Biography '41' reveals another side of George W, but has few surprises

If you thought the Milibands were a complex pair, that brief, brotherly battle for the Labour leadership pales beside the dynastic currents within the Bush family and the relationship between its two members who have actually held America's most powerful office.

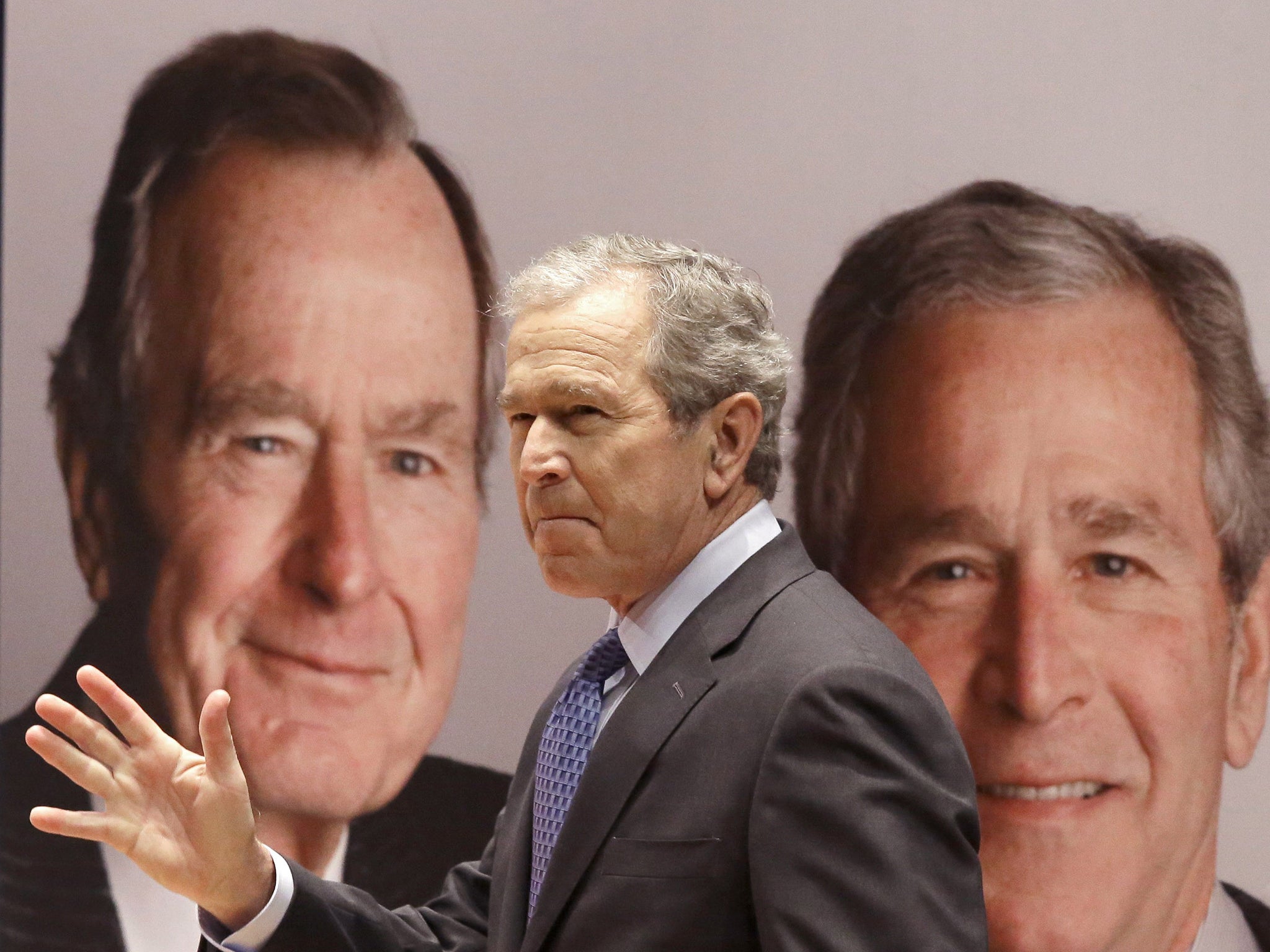

As a young man, George W Bush was a party boy, by his own admission the black sheep among his siblings. As president, he sometimes seemed deliberately to take an exactly opposite tack from his father George HW, as if to escape from his parent’s towering shadow and prove he was his own man.

Bush père wasn’t much for “the vision thing”. His son, by contrast, loved nothing more than bold, broad-brush action, spurred by ideals, right or wrong. The father didn’t invade Iraq, but W did. The father raised taxes. The son’s first major act was to push through the biggest tax cuts in US history.

All of which has led to a cottage industry of armchair psychology among the pundit class. Some likened the relationship to a Shakespearean drama; amateur Freuds even speculated about an Oedipus complex – that W was his mother’s boy who unconsciously detested his father.

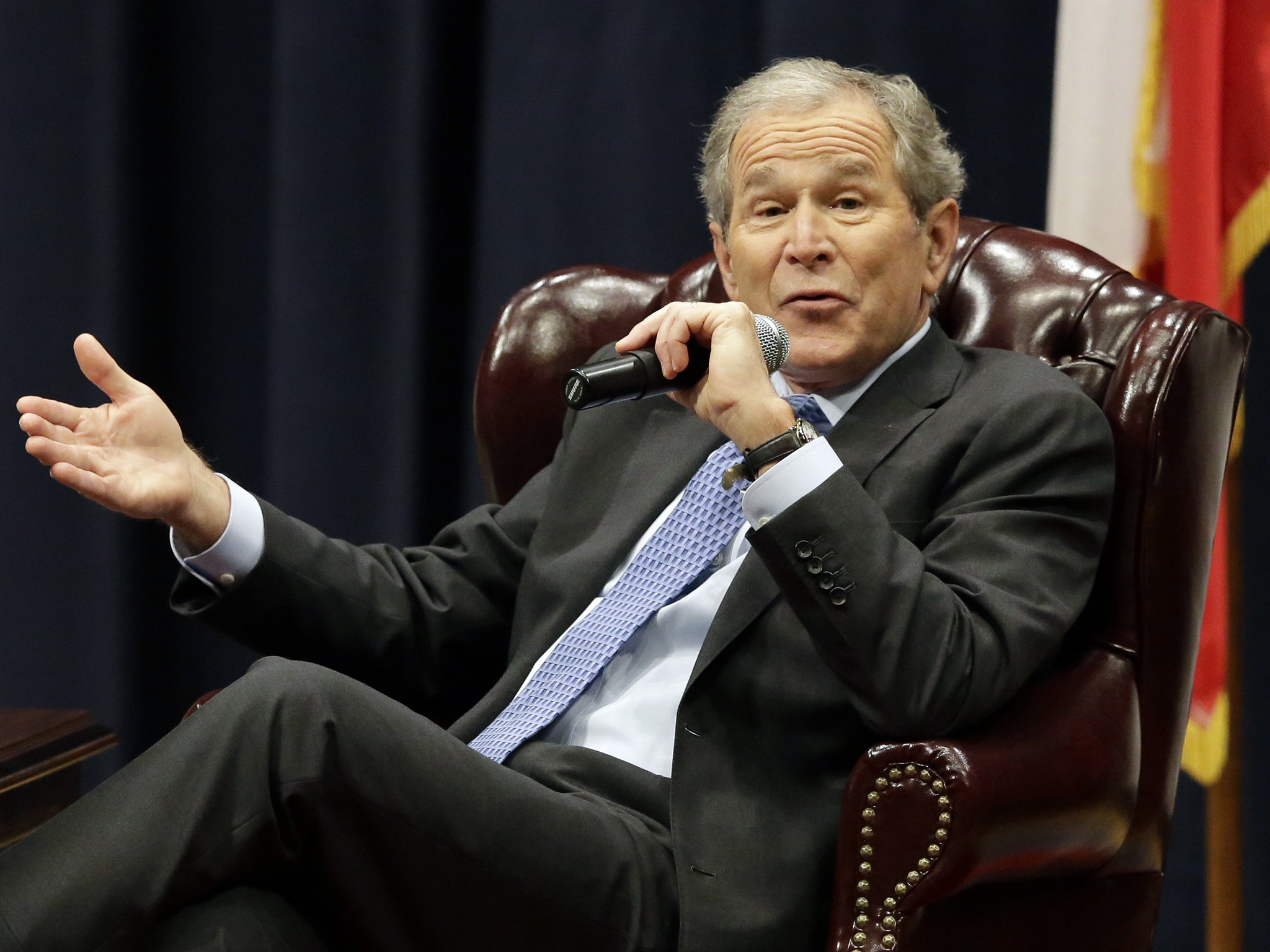

How mistaken we have been. The black sheep has now produced a book, 41: A Portrait of my Father. It’s by turn affecting, cloying, folksy and funny (amid the vitriol heaped upon him by detractors, it’s easy to forget that Bush junior – “43” in the presidential numerology used by the family – had a pretty sharp sense of humour.) But essentially, he says in his preface, it’s a “love letter” running to 294 pages, “a personal portrait of the extraordinary man who I am blessed to call my dad”.

The germ, intriguingly, was planted by the daughter of the historian David McCullough, who wrote the definitive biography of John Adams, America’s second president. As with the Bushes, Adams’s son John Quincy became president in his own right (“6” in Bush parlance). But, Dorie McCullough Lawson told George junior, her father’s regret was that John Quincy never wrote about his father. “For history’s sake,” she said, “I think you should write about your father.” So 43 did – and quickly, to make sure his 90-year-old dad was still around to read it.

In fact 41 the book doesn’t contribute much to history, or even throw great new light on its subject. The Bush senior that emerges is the conventional image of the man: decent, slightly uncomfortable with family intimacy, a patrician in his ways.

Bush junior is different. Retirement seems to have brought out the inner artist in him. The father, in keeping with a late-life birthday habit, went skydiving when he turned 90 last 12 June. The son has already produced a self-justifying political memoir, Decision Points, and has emerged as a surprisingly competent painter.

The book contains few revelations, the most interesting of them that his father contemplated not running for re-election in 1992, in part out of weariness, in part because his son Neil, George W’s younger sibling, was under investigation in a banking scandal.

Most moving is 43’s account of the death of Robin, his sister, of leukemia at the age of four, in 1953. “In one of her final moments with my father,” he writes, “Robin looked up at him with her beautiful blue eyes and said, ‘I love you more than tongue can tell.’ Dad would repeat those words for the rest of his life.”

In fact, 41 doesn’t need this kind of paean. In retrospect, his presidency is looking better by the day, especially in foreign affairs where Barack Obama hasn’t exactly excelled, and where his son, by invading Iraq in 2003, committed arguably the biggest foreign policy blunder in American history.

The elder Bush wasn’t just as decent a man as you’ll find in politics, with a remarkable gift for personal relations, but was the diplomatic master who in 1991 knew not to go all the way to Baghdad, and whose tact and refusal to gloat contributed much to the fact that the Soviet Union expired peacefully, rather than in a bloodbath. But if there was a rift – Oedipal or otherwise – between father and son, the book is proof that it has long since healed.

Bush junior dismisses such theorising as “psychobabble” – alas, though, this may not be the end of it. Quite possibly, his younger brother Jeb will run for the presidency in 2016; according to George W, both he and his father are urging Jeb to do so; in which case a “45” might be added to the Bushes’ White House shorthand.

But here too there is a twist. If 43 was once the black sheep of the family, Jeb was the one who Bush senior felt had real political promise. The pivotal year was 1994. George junior ran for governor in Texas and won, but Jeb lost his bid for the governorship of Florida. Had he won, he might have been the Republican nominee in 2000. Or maybe America would have experienced its version of Miliband fraternal warfare.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks