Civil war battle rises from the ruins of Old Fredericksburg

Perhaps the Yankee boys from Company C had tumbled into the basement on Princess Anne Street to escape the rebel snipers hidden in the ruined buildings outside.

Maybe they had sought refuge after the suicidal slaughter on the nearby heights, where the Confederates packed behind a stone wall had mowed down rank upon rank of charging Union lads.

Or maybe they were among the Northern soldiers who pillaged Fredericksburg as the battle here unfolded in a federal defeat.

All the archaeologists have to go on are the things they left behind — bullets, charred clay pipe bowls, buckles, buttons and other refuse of war.

Last month, experts finished unearthing, in the basement of a long-vanished house, a trove of artifacts that appears to date from the Civil War's Battle of Fredericksburg — 150 years ago next month.

Thousands of items, dropped, discarded or forgotten, were dug from the site, which became sealed in time after the Union army retreated from the December 1862 battle, and the house on the site burned down.

They were tantalizing finds — bullets that had been unloaded from muskets; two brass letters, "C," likely from Union hats; two number "2" insignia, perhaps indicating the soldiers' regiment.

There were also knapsack hooks, the finial from a cartridge box, and the remains of ration tins, almost all of it the equipment of Yankee soldiers, archaeologists said.

For a century and a half, it stayed buried. After the war passed, modern buildings came and went on the site, and the soldiers who fought at Fredericksburg aged, died and faded into memory.

Then, in September, the Glen Allen, Va., firm Cultural Resources began an archaeological dig at the behest of the city of Fredericksburg, prior to the construction of a new court building.

As the archaeologists peeled back the layers of dirt and history, artifacts by the thousands began to emerge.

"I had never really sunk into a Civil War feature like that, so it was child-like for me," said Donald Sadler, a project archaeologist. "You'd take your trowel and go across the one layer and it was 'chink, chink, chink, chink, chink.' The bullets were that numerous."

The experts recovered "boxes of this stuff," Taft Kiser, another project archaeologist, said recently at the company's headquarters, where the items are being curated. The dig, which cost about $70,000, ended Oct. 19.

Ellen M. Brady, the firm's president, said the basement had become a time capsule, encased most recently beneath the concrete slab of a modern building, since torn down.

"We think that the house that was there during the Civil War was burned, either during the battle in 1862 or shortly thereafter," she said. "What the archaeology is telling is that sometime after this battle . . . this house was gone."

"There's no 20th-century trash," she said. "There's no co-mingling with later material.. . . It's very discrete, which is rare."

She said some of the items — glass ink wells, a comb, a watch chain — suggest that the Yankees' stay in the basement might have been for more than a few hours.

Also intriguing were a pile of bullets found in a corner of the basement that bore indications that they had been loaded in muskets but were extracted without being fired.

The basement occupants may have charged "up the hill as far as they could, and . . . kind of recoiled back looking for shelter," Kiser said.

The Union army fought over, and then occupied, Fredericksburg for several days during the battle. "We think they were basically just camped out," Brady said, "taking refuge in the houses of Fredericksburg before they were expelled or moved on."

The battle was one of the Union's most disastrous defeats.

A Northern army of about 120,000 men, under newly installed commander Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, sought to cross the Rappahannock River and attack 78,000 Confederates under Gen. Robert E. Lee, assembling at Fredericksburg.

Burnside crossed the river on pontoon bridges and seized the town. He then launched a series of futile assaults on Rebels dug in behind a stone wall at a place called Marye's Heights, on the western outskirts.

About 12,600 of Burnside's men were killed, wounded or missing, according to the National Park Service. Lee lost less than half that and remarked to a subordinate, "It is well that war is so terrible. We should grow too fond of it."

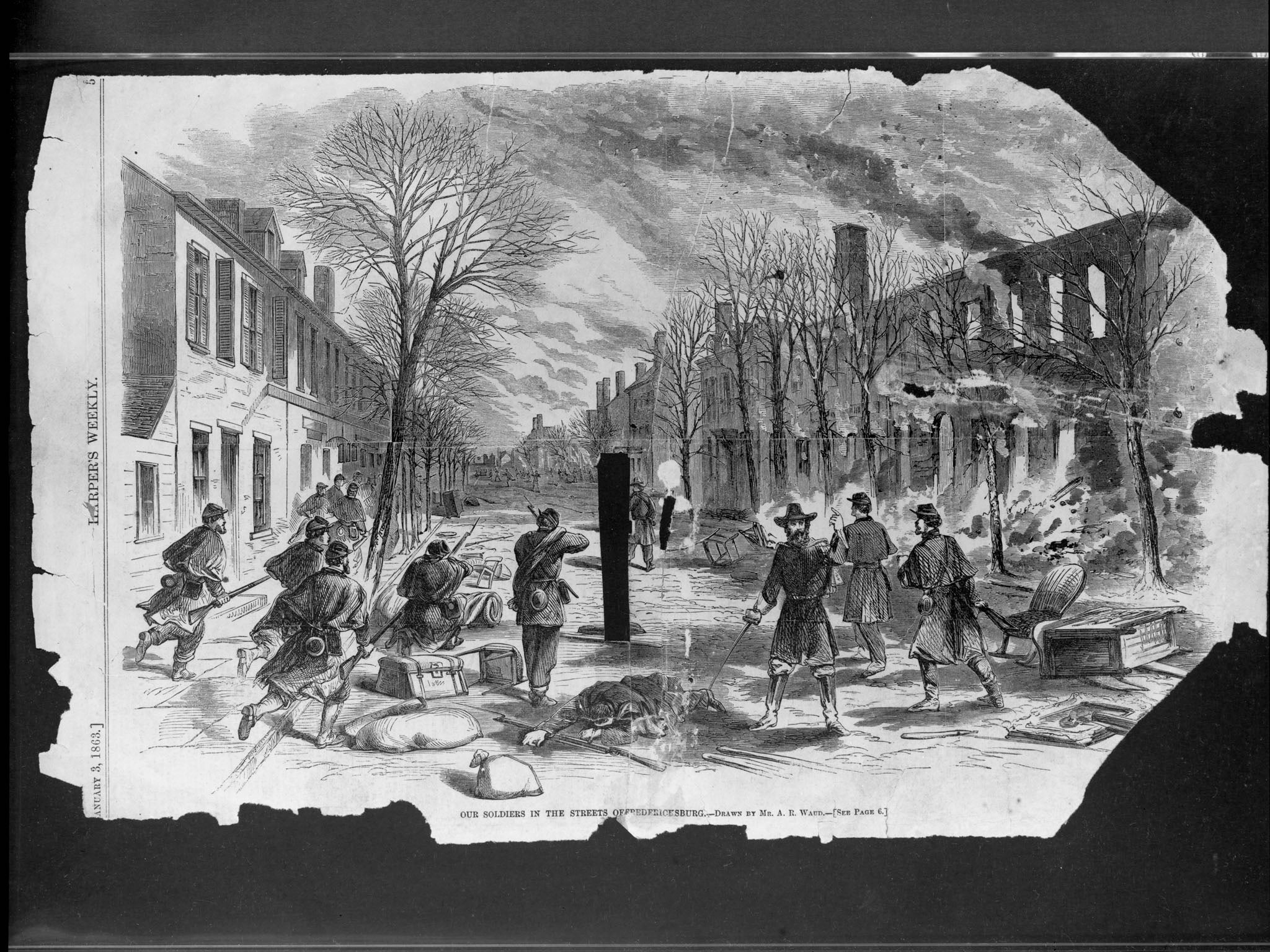

But less discussed aspects of the battle were its house-to-house street fighting — the first on the American continent, according to historian Francis Augustin O'Reilly — and the despoiling of the town by the Yankees before they left.

"The war was embittered here to a degree that really very few other battlefields can match," said John Hennessy, chief historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

"That was because of, at least for the South, this image of civilians under duress, civilians as refugees, civilians' homes being bombarded . . . and then, of course, soldiers entering homes and looting them," he said.

There are accounts of drunken Union soldiers plundering houses, slashing oil paintings, and cavorting through the streets in women's clothing. "The sacked and gutted town (had) the look of pandemonium," a Union soldier remembered later.

Hennessy said he believes it is most likely the artifacts from the basement are "associated with that moment . . . when Union troops committed what Southerners saw as a grave offense."

The city "had been reduced to ruins," O'Reilly wrote of the battle — setting the stage "for the way modern armies would fight from then on."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks