Harmony Montgomery was murdered by her father. These are all the systems that failed her

A five-year-old girl slipped through the cracks, was killed by a parent, and then was left undiscovered for two years. Kelly Rissman and Andrea Blanco report on everything that led to the little girl’s death

The storm of unfortunate events that led to a Massachusetts court awarding custody of Harmony Montgomery to her father would eventually prove fatal.

For the first four years of her life, Harmony’s childhood had been a lot like her little brother Jamison’s. They were born two years apart to a mother who was actively struggling with substance abuse issues and constantly found themselves in and out of foster homes.

“The trauma that they had been through at a very young age ... All they really had was each other. Harmony was Jamison’s only constant,” Blair Miller, who adopted Jamison along with his husband Jonathon Bobbitt-Miller, tells The Independent.

Jamison officially became a Miller in November 2019 and a week later, the family gathered to celebrate the little boy’s birthday at their Boston home. That same weekend, just over 50 miles away in Manchester, New Hampshire, Harmony was killed. She was five years old.

“All I can think of is, ‘Gosh, we were celebrating Jamison’s birthday when Harmony was being beaten in the back of a car,” Mr Miller said.

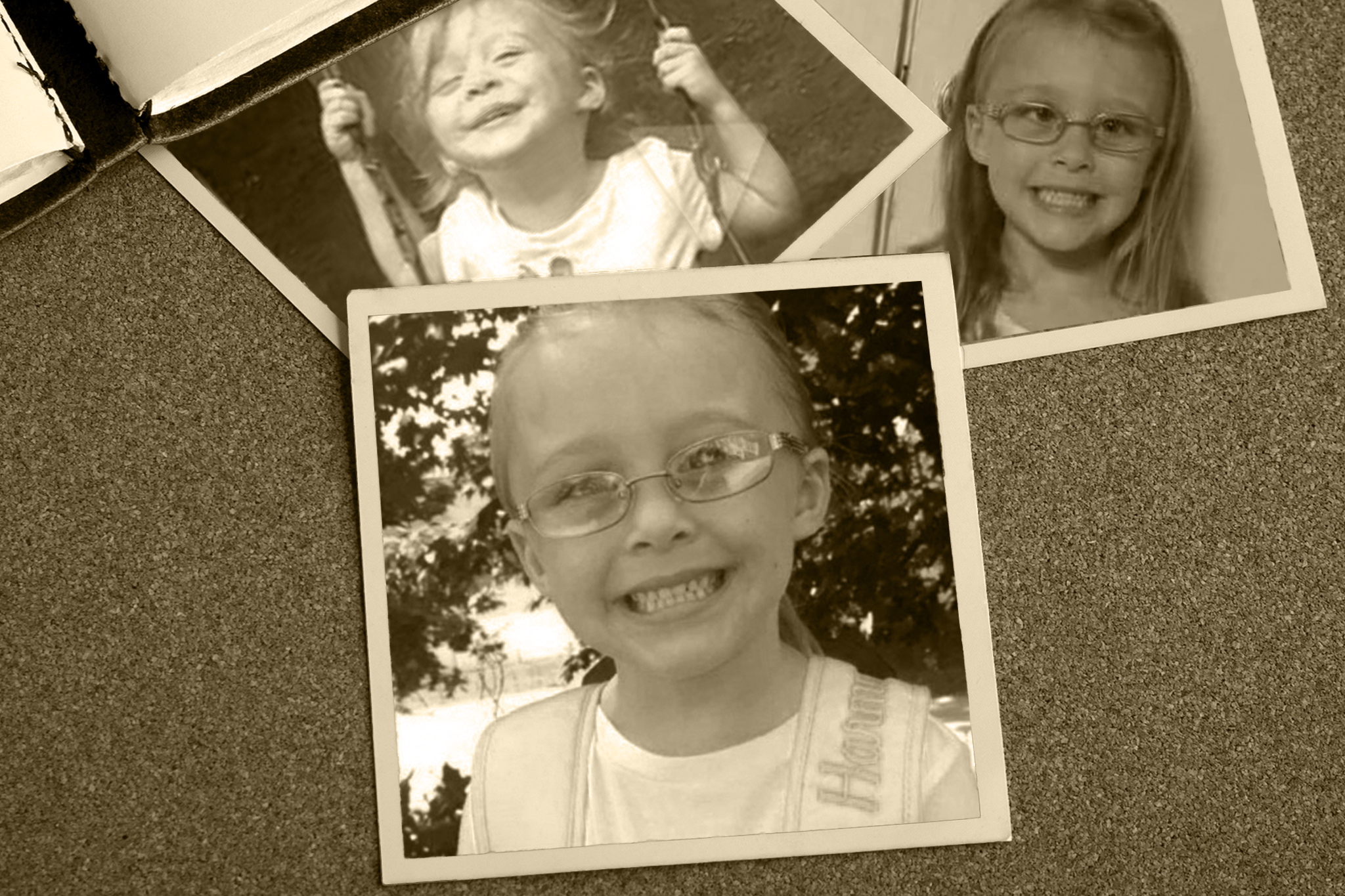

The Millers had inquired about adopting Harmony, a rambunctious little girl with an infectious grin who was blind in her right eye, but were told that would not be possible. The Massachusetts Department of Children and Families (DCF) informed the family that Harmony had been reunited with her biological father, Adam Montgomery.

Montgomery was found guilty by a jury in late February of beating Harmony to death after she had a bathroom accident.

A constellation of missed warning signs, systemic failures, inconsistent laws across two states, and vague policies resulted in Harmony being placed in the hands of her father, who had a violent criminal history and was in jail at the time she was born.

“It was one decision after another that put her on a path of lethality with her father,” Carol Erskine, a Massachusetts child advocate, juvenile court judge, and author of an upcoming book about Harmonytold The Independent.

From June 2014, when DCF opened the case, to February 2019, when her father was awarded custody of Harmony, the DCF case management team never completed an assessment of him, the Massachusetts Office of the Child Advocate (OCA) noted.

Just 40 hours of visitation and an extensive criminal history

Perhaps if a proper assessment of Adam Montgomery had been conducted, agencies would have noticed his lengthy criminal history, which includes everything from robbery to armed assault.

“There was just a list of dangerous crimes that made him a clear risk, in my opinion, to being able to parent their child,” Ms Erskine said.

The former judge explained that when determining the placement of a child, a judge will only consider a criminal past if the crimes are “relevant”. For example, “when there’s a record of ongoing unabated violence, with weapons and crimes against individuals, then it becomes more relevant in terms of parenting.”

Another red flag appears to have been ignored when deciding to award Harmony’s father custody: the lack of time he had spent with her during her life.

“Mr Montgomery was in and out of Harmony’s life since birth, not consistently visiting with her for more than four to six months at a time, with long periods of no contact,” the Massachusetts OCA’s 2022 report states. One gap between Montgomery’s visits to Harmony spanned 11 months.

The OCA estimated that the child had spent 40 hours across 20 supervised visits with her father from the time she was born to age four and a half. The report also noted that there is no evidence that her father tried to “understand or accommodate” her visual impairment or the emotional trauma she had already endured in her young life.

Ms Erskine laid out a series of issues in court when Montgomery was awarded custody. The DCF attorney, while opposed to the father being awarded custody of Harmony, did not pursue important lines of inquiry – such as his parental capacity, job stability, housing situation, or understanding of her visual impairment – according to the Massachusetts report. Because DCF’s case was “extremely weak”, the judge didn’t hear substantial relevant evidence, Ms Erskine said.

On top of this, Harmony didn’t have a court-appointed child advocate. “If there had been an independent voice for Harmony, things might have been very different because the judge might have heard information that was not conveyed to the court by the lawyers,” Ms Erskine added.

Regardless of the dearth of information, the judge awarded Adam Montgomery full custody.

“This was a case that was open with the court for four years and eight months and the trial lasted somewhere between six and eight hours,” Ms Erskine said. At the same time, Harmony’s mother Crystal Sorey had a scheduling conflict in a different court regarding the care and protection of Jamison, Harmony’s half-brother. Harmony’s hearing therefore proceeded without her mother.

Harmony was then sent to live with her father in New Hampshire.

Interstate issues played big role in lack of safety checks

Moving to another state opened the floodgates for more missed warning signs.

Ms Erskine said that “the major problem” in the case is that there are different interpretations by Massachusetts and New Hampshire of the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children (ICPC) – which is a law enacted across all 50 states that requires check-ins about the child’s welfare.

The ICPC requires an investigation, including a criminal background check and a home study.

The Massachusetts juvenile court judge requested an expedited ICPC to analyse what placing Harmony in Adam Montgomery’s care – in another state – would look like. However, the Massachusetts report said that the New Hampshire ICPC Compact Administrator had not acted on the ICPC request by the date of the February 2019 hearing.

So “Harmony was placed in the custody of Mr Montgomery without a completed ICPC,” the Massachusetts report states.

Cassandra Sanchez, a child advocate at the New Hampshire OCA, explained that Massachusetts had sent an ICPC request to be completed by New Hampshire but some documents had been missing.

“The sending state is the one that needs to follow up,” she said. Ms Sanchez also worked at the Massachusetts OCA during the Montgomery case. She said it was “surprising” that the judge “moved forward with placement of the child to a parent before that was completed”. There was never a home study at Adam Montgomery’s house.

Ultimately, the judge determined that the ICPC did not apply, and the DCF attorney – the only attorney to argue that the ICPC applied to Harmony’s case – did not appeal that decision, the Massachusetts report states.

When the ICPC didn’t happen, it “left Harmony alone in a home with a man who had a dangerous, violent criminal past”, said Ms Erskine.

The beginning of the end for Harmony Montgomery

It took just months after Harmony moved in with her father for abuse allegations to surface.

In July 2019, Kevin Montgomery, Adam Montgomery’s uncle, reported that Harmony had been abused after seeing a black eye on the little girl – and said that her father had admitted causing it.

“I bashed her around this house,” Kevin Montgomery said Adam Montgomery had told him. The uncle said he contacted DCYF and had also noticed that Adam had subjected his daughter to other forms of “abusive discipline”, such as scrubbing a toilet with her toothbrush and being “spanked hard on the butt”.

Michael Montgomery, Adam Montgomery’s brother, also told investigators he “had concerns that Adam was physically abusive” to the child and was “super short” with her.

New Hampshire DCYF visited the home the same day as the call and decided the claim was unfounded. However, as the New Hampshire report notes, the DCYF worker only saw the child for a fleeting moment. It said: “This assessment was conducted as Adam Montgomery and Harmony were entering their vehicle and departing.”

A few weeks later, in August, when the worker conducted a second, “more detailed assessment”, they noticed a red mark in her eye and faded bruising under her eyelid, the report says. Harmony, her father and his wife, Kayla Montgomery, all told the worker that the child had been accidentally hit with a toy lightsaber while playing with a sibling.

After yet another assessment in October 2019, the worker rated the situation as “high risk” for future child welfare involvement.

No one saw or heard from Harmony again.

A murder left unreported for two years

Police have narrowed down the window when Harmony Montgomery died to between late November and early December 2019.

At the trial, the court heard graphic details of the little girl’s death. According to the testimony of her stepmother, Harmony was beaten to death after she soiled herself but Montgomery and his estranged wife Kayla did not realise for some hours that she was dead. Kayla Montgomery was the key witness at Montgomery’s trial after reaching a plea deal on unrelated charges of perjury. She is currently serving an 18-month prison sentence and has not been charged with any offence against Harmony.

According to the stepmother, the little girl made “weird moaning noises” as she lay in the back of the car after the beating. Her severely bruised, tiny body was covered by a blanket and her face was dirty with blood from beatings in the days before.

The Montgomerys drove to a Burger King and then to a friend’s apartment complex to buy drugs before they realised Harmony was not breathing, Kayla Montgomery said. For the next two months, Adam Montgomery went to horrific lengths to reduce Harmony’s remains, before he disposed of what was left of her in March 2020.

Still, two years on from her death, no authorities were even looking for Harmony.

In January 2020, the New Hampshire DCYF received yet another report about the Montgomery household; Adam Montgomery informed the agency that Harmony was not there, and instead was living with her mother in Massachusetts.

DCYF proceeded to try to get in touch with Crystal Sorey, to no avail. Both state reports say that she did not return their one call and voicemail attempting to contact her.

“There was not a strict guideline in place at the time for [DCYF] to have to connect with the parents; they made attempts,” Ms Sanchez explained.

The Montgomery household received numerous child welfare reports from January through March 2021 – none of these complaints pertained to Harmony. When agents asked about Harmony’s whereabouts, Adam Montgomery said that she was with her mother and he hadn’t seen his daughter in a year, state reports say.

Strangely, both state reports make no mention of the little girl from March 2020 – when agents tried, unsuccessfully, to contact Ms Sorey – until a year and a half later, in September 2021. The gap underscores that seemingly no one had been trying to keep tabs on the little girl in the interim, despite neither agency being able to confirm where she was staying.

It wasn’t until September 2021, when someone close to Ms Sorey asked the New Hampshire child welfare agency about Harmony, that anything was done. That person said that the child’s mother hadn’t seen her daughter since Easter 2019 and hadn’t been able to get in contact with Adam Montgomery in order to visit her daughter.

Only then did New Hampshire’s child welfare agency confirm that Harmony had never been registered for school in the state. At that point, she would have been seven years old.

So, in December 2021, the search for the girl began, with agencies believing they were looking for a missing seven-year-old. On 31 December, the same day that police publicised Harmony’s disappearance, New Hampshire officers found the little girl’s father living in his car. When asked where his daughter was, he provided “contradictory” explanations, reports say.

Days later, he was arrested and charged with second-degree assault, interference with custody and endangering the welfare of a child.

In October 2022, Adam Montgomery was charged with murder. More than four years later, Harmony’s body has yet to be found.

A jury found Montgomery guilty of second degree murder in February. His sentencing is scheduled to take place on 9 May.

A loving family who would have adopted her

Blair Miller and his husband watched Montgomery’s trial with “an eye open” and the other closed, he told The Independent before the jury reached its verdict in February. Naturally, a child murder case would have its share of grim details, but the information that emerged during the two and a half weeks of proceedings proved disturbing beyond comprehension.

During closing arguments, prosecutor Ben Agati’s voice cracked with anger and outrage.

“The only parts of Harmony that are left will be with you in that deliberation room, on that pink toothbrush, and on that part of [bloodied] ceiling wall,” Mr Agati told jurors before deliberations began on Wednesday, of the last objects known to contain Harmony’s DNA. “And the other parts of her body, her torso, her face, her eyes, that smile ... only the defendant, as we sit and stand here today, knows where they are. He can’t afford to say where they are, because the evidence contained on them will show that he caused her death, so she won’t get the burial that she deserves.”

Although Harmony’s body was abused in unimaginable ways, her legacy lives on in her little brother. After he was adopted by the Millers, Jamison looked for Harmony in every blonde little girl he saw while out with his parents and siblings.

“We were talking to his mom about trying to figure out where exactly Harmony was because Jamison was so determined to want to keep that relationship. He would ask about her a lot. We’d be at a park and he’d say that’s Harmony, off in the distance,” Mr Miller said. “As a dad, you want to help fix that situation.”

The Millers would have gladly adopted Harmony. When they were told Jamison had a sister, they reached out to Montgomery via Facebook messages about her living with her biological father, but they never heard back.

“We had always said, ‘If anything changes, we would want to keep them together’,” Mr Miller said. “We feel a lot of guilt from that because we wish we could have done more. We wish we would have pushed harder. We were trying to keep a relationship between Jamison and his sister.”

Jamison is not yet aware of the horrifying abuse his sister endured but understands that Harmony is no longer alive. His fathers welcome conversations about Harmony and have tried to fill in the gaps with age-appropriate information.

On Jamison’s bedroom door, the Millers have placed a picture of him and Harmony. In the photo, they’re both smiling. Harmony is wearing her round glasses and a shirt featuring Minnie Mouse, her favourite cartoon character. Jamison is holding a stuffed animal tight in his hands. It’s a frozen moment in time of the special bond they once shared, before Harmony’s life was taken and Jamison’s was irreparably changed.

“He still very much talks about his relationship with Harmony and what she means to him,” said Mr Miller. “Just the other night, he was saying during his evening prayers, ‘I pray to God that he could just do one thing and that’s to bring Harmony back to life’.”

‘What has been done so there’s not another Harmony?’

There have been some changes implemented to address the wide range of missteps that occurred in Harmony’s case.

A spokesperson for the Massachusetts OCA told The Independent that its child welfare agency had decreased the caseloads of its staff attorneys. Similarly, the New Hampshire OCA said its child welfare agency workers now have a more manageable case-load that is “closer to the [proposed] national standards,” Ms Sanchez said.

Since this case, New Hampshire has also put in place new policies for how children are evaluated after the child welfare agency receives a report. New Hampshire child welfare agents are now required to see children within a certain time frame and ensure they are “directly laying eyes on the child and not seeing a child in passing”, Ms Sanchez said. Hopefully, this will avoid another fleeting moment where an agent spotted Harmony from afar while she got in a car. The agents are also required “to sit down and meet with the child separate from the parent and potential perpetrator”, she added.

There are also tighter definitions pertaining to the child-parent relationship.

On top of this, seemingly in order to address Adam Montgomery being awarded custody after seeing his daughter for just 40 hours, Massachusetts and New Hampshire have signed a memorandum of understanding requiring parents to prove that they have a pre-existing relationship with a child.

If the parent and child don’t have a pre-existing relationship or it can’t be proven, then the two states have agreed that the parent will undergo a home study process, Ms Sanchez explained.

After Adam Montgomery told the New Hampshire child welfare agency that Harmony was living with her mother, the agency tried contacting Ms Sorey once – without follow-up. Now, the agency is required to continue to try to get in touch with the parent until they connect and are able to validate the whereabouts of the child. If that parent says they don’t have the child, the agents must then “take steps to seek out where else that child may be”, Ms Sanchez said.

While some state policies have been addressed, Ms Erskine has her sights set on changing federal legislation. She hopes to alter the language of the 1997 Adoption and Safe Families Act to make a home study and follow-up mandatory in the cases in which a child is to be with a parent in another state.

The New Hampshire legislature announced in February that it had started the “Harmony Commission”. The house speaker said that a “committee on the Division for Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) is charged with considering all matters on due process and practices concerning DCYF” and can “make recommendations for future legislation”. Ms Sanchez said the commission seems like it will explore “parents’ rights and their due process. And for us, that’s the opposite of what we need to be looking at right now”. She added, “Children’s needs need to be at the forefront.”

“It comes back to … what’s going to happen? After this verdict, what are we going to do?” Mr Miller told The Independent. “I know people are outraged but how do we harness that into creating change so there’s not another Harmony?”

At the Miller household, Harmony is a central focus. The couple have met lawmakers in Massachusetts and DC to discuss potential ways to avoid history repeating itself.

Every year, the Millers celebrate Harmony’s 8 June birthday. It’s a tradition that dates back to when she was reported missing.

Last year, they held the celebration at the Potomac River in DC.

“Jamison said, ‘Let’s get some flowers and go put them in the river’,” Mr Miller recounted. “He said, ‘All rivers eventually lead to heaven’. He wanted the flowers to reach her.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks