Donald Blankenship trial: Jury ponders fate of ex-coal-mining kingpin charged with safety failures resulting in 29 deaths

In a surprise move, defence attorneys for the former chief executive of Massey Energy rested its case without calling a single witness

Threatened by new rules to curb global warming, the American coal community has found a morbid distraction from its woes in the trial – now nearing its conclusion in West Virginia – of a former kingpin of the industry accused of cutting corners on safety before a deadly accident in one of his mines.

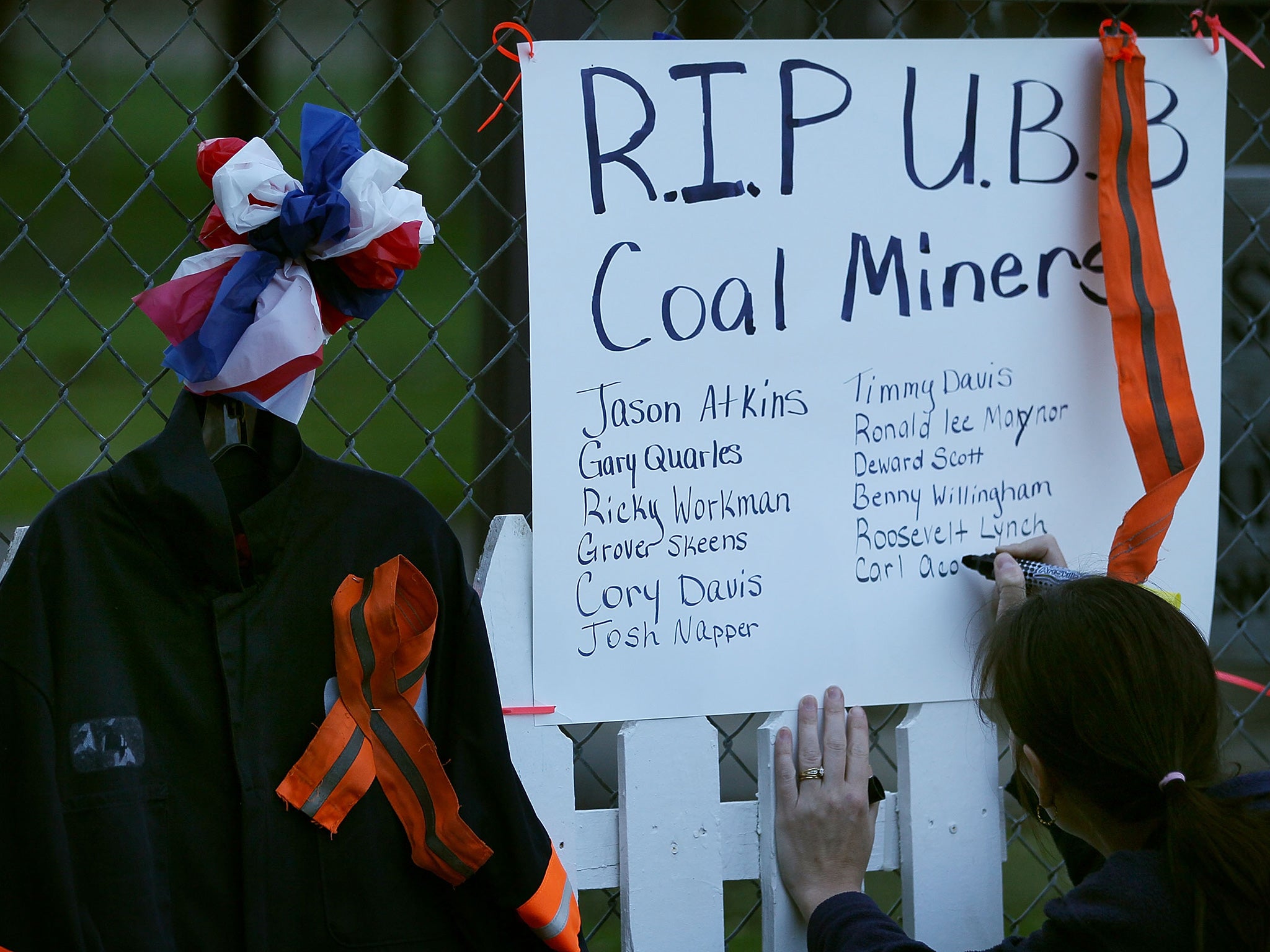

After weeks of testimony, jurors are shortly set to begin deliberating the fate of Donald Blankenship, the former chief executive of Massey Energy. The company was the owner of the Upper Big Branch mine at the time of a 2010 explosion that killed 29 miners, making it the deadliest mining accident in the US in decades.

This week, the defence startled the court in Charleston by declining to call a single witness, instead resting its case even before starting it. The decision was meant to convey confidence that the prosecution’s case had already been discredited during cross-examination of its witnesses. But the step also ensured that Mr Blankenship would not be called to the stand to testify, a move that would have carried big risks.

Once a towering figure in the state, Mr Blankenship, 65, saw his fortunes crash after the 2010 catastrophe. While he was not accused of direct culpability in the 29 deaths, a federal investigation into the accident led to charges that he conspired to break mine safety laws and misled both regulators and investors about the safety measures that had been put in place – or not – in Massey mines.

If convicted, Mr Blankenship, who denies the charges, could face up to 30 years in prison. But in any event, the closely-watched trial in Charleston, the state capital, has served as a poignant sub-plot to the greater narrative of the industry’s painful contraction in West Virginia and other states.

In closing arguments, prosecutor Booth Goodwin described Mr Blankenship as an “outlaw” who ran a massive criminal conspiracy at the Upper Big Branch mine. “The defendant dictated [the conspiracy] to all and operated Massey ... as a lawless enterprise,” he told jurors. “His method of operation was to violate nearly every law on mine safety in the book.”

Massey Energy itself was purchased by a competitor, Alpha Natural Resources, for $7.1bn in 2011. But in August, Alpha filed for bankruptcy protection as it has struggled to cope with a rapidly darkening outlook for coal, precipitated in part by fast-falling prices and competition from natural gas.

Still more threatening is a new plan to slash CO2 emissions issued by President Barack Obama, who is determined to show that the US is leading by example at the world global warming summit in Paris which opens in two weeks. The rules will force electricity-generating companies to accelerate converting power stations from coal to gas. Coal currently accounts for one-third of US power generation.

Dubbed a “War on Coal” by Republican detractors, there is unlikely to be any change of policy if Hillary Clinton, the likely Democratic nominee next year, succeeds Mr Obama in the White House. More importantly, pledges by other nations in Paris to cut emissions, notably by China, would surely depress prices further and narrow export opportunities for US producers.

The difficulties at Alpha Natural Resources, one of America’s largest producers, have been attributed partly to obligations it inherited to cover Mr Blankenship’s soaring legal costs. Among those who testified against him was a former Massey subsidiary president, Christopher Blanchard. His unit was in charge of operating the Upper Big Branch mine at the time of the accident.

Testifying under an immunity agreement, Mr Blanchard said safety violations at the mine could have been resolved by hiring more people and committing more money to safety. He also said on the stand that he thought at the time that the defendant had concluded it was more cost-effective to pay whatever fines were levied against Massey than to spend whatever would be needed to comply with safety rules.

As it built its case in a trial that began on 1 October, the prosecution was also able to take advantage of Mr Blankenship’s habit of secretly tape-recording telephone calls made in his office while he was chief executive. Jurors heard one tape in which Mr Blankenship comments that a secret company memo about its mining operations should be kept secret because it would be a “terrible document” if it were ever handed over in any legal proceedings arising from fatalities at any of its mines.

Jurors were also reminded that if there was a time when coal was king in West Virginia, then those who ran it expected to be treated like royalty also. On one tape, Mr Blankenship was heard grousing that the Massey board wanted to cap his salary at $12m, calling board members “so unappreciative”, and adding sarcastically that he “can’t go to the grocery store and buy groceries with [stock] options”.

Blankenship's method of operation was to violate every law on mine safety in the book

History shows that ex-CEOs on trial can hurt themselves if put on the stand. A notably example is Jeffrey Shilling, former head of Enron, the defunct energy trading giant. He was convicted after nearly a week on the stand defending his actions in the run-up to the energy giant’s implosion.

But Judge Irene Berger admonished jurors not to draw conclusions from the defence decision not to put Mr Blankenship on the stand. “The defendant has exercised his constitutional right not to testify ... and it cannot be used in your deliberations in any way,” she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks