Ebola outbreak: Billy Graham’s son declares righteous war on the virus

A Christian charity’s efforts to save missionaries trapped in Africa by the crisis have been justifiably praised. But doubts remain about its evangelical motives

Dent Thompson had never heard of Samaritan’s Purse when the Christian relief group called last month and asked for his help.

Samaritan’s Purse and another global ministry group, SIM, were scrambling to transport two Ebola-stricken US missionaries from Liberia to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, for treatment. They had learnt from government officials that Mr Thompson’s company, Phoenix Air Group, had a Gulfstream III jet with an isolation unit developed for emergency medical evacuations. They wanted to send the aircraft to West Africa right away.

“They were distraught that two of their people were stuck with no apparent way to get them out,” Mr Thompson recalled. “Samaritan’s Purse indicated to us that they would hire anybody with the ability to pull them out… We gave them a price and they agreed.”

The drastic measures to rescue the missionaries point to the global reach and deep pockets of Samaritan’s Purse, which last year raised hundreds of millions of dollars in contributions and received tens of millions in federal grants.

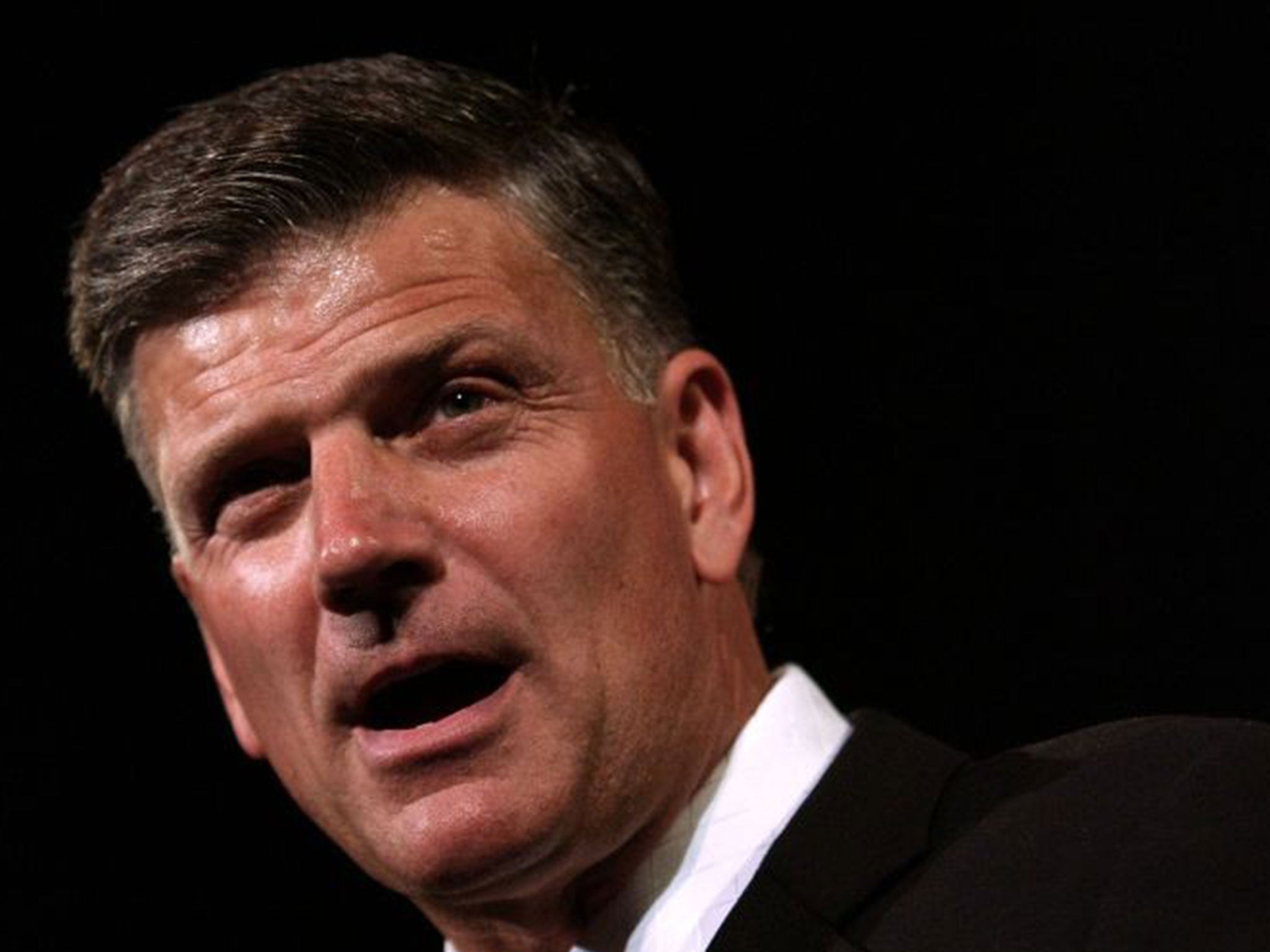

The Ebola outbreak has made it clear how much governments, especially those of poorer countries, rely on non-profit groups to deliver medical care and supplies and sound an early alert on health emergencies. That has brought attention to Samaritan’s Purse, a sometimes controversial group run by Franklin Graham, the son of the Rev Billy Graham.

Driven by a desire to spread the Christian message, it is a sophisticated international enterprise, able to navigate the logistical and regulatory challenges necessary to rescue stricken missionaries and gain access to a promising experimental treatment that was given to the workers.

Mr Thompson declined to disclose the price for evacuating the two missionaries – Kent Brantly, a doctor with Samaritan’s Purse, and Nancy Writebol, who along with her husband was working for SIM at a hospital in Liberia. But SIM president Bruce Johnson has said that the relief groups have spent more than $2m (£1.2m) on the transport and treatment of the missionaries. “This came straight out of their bank account,” he said of the two air ambulance flights his company provided, noting that the US government helped only with logistics. “You can’t do this unless you are very well financed.”

Ken Isaacs, a vice-president at Samaritan’s Purse and a former director of the foreign disaster assistance arm of the US Agency for International Development (Usaid), last month recounted how the group had secured ZMapp, an experimental Ebola treatment, to send to the two infected US missionaries.

The North Carolina-based Samaritan’s Purse and SIM are NGOs, operating internationally. In an informal partnership, Samaritan’s Purse helps staff hospitals run by SIM in Africa. Because of the Ebola outbreak, the two groups have evacuated dozens of “non-essential” personnel from Liberia. Samaritan’s Purse has 350 staff members, mostly African nationals, remaining in Liberia, providing support and working on public awareness campaigns, said a spokeswoman for the group.

With its headquarters in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Samaritan’s Purse has neither the big name nor the contacts of groups such as Médecins Sans Frontières and Care International, a global humanitarian agency. But its most recent financial disclosures detail what a well-funded, far-reaching organisation it has become in the 35 years since Mr Graham took the helm.

Last year, the group had roughly $460m in revenue, records show. It maintains offices in Canada, Australia and Britain, and has more than a dozen aircraft situated around the world to shuttle around staff and to help reach remote communities or those hard-hit by natural disaster.

The organisation, which is non-denominational, has rebuilt churches and provided humanitarian assistance to hundreds of thousands of people affected by the civil war in South Sudan. Its medical arm helped to staff dozens of hospitals in nearly 30 countries last year. But the growing worldwide ministry of Samaritan’s Purse has not been free of controversy.

During the 1990-1991 Gulf War, Franklin Graham drew a sharp rebuke from General Norman Schwarzkopf after the group tried to arrange for US troops stationed in Saudi Arabia to distribute Arabic-language Bibles – an undertaking that violated an agreement between the Saudi and American governments.

Mr Graham himself has proven a polarising figure over the years. He stirred widespread criticism after the 9/11 attacks when he referred to Islam as a “wicked” and “evil” religion.

Those controversies aside, the group maintains a reputation of being among the first to combat the worst public health crises around the world.

“Given the remote and hard-to-reach areas they work in, there’s been many instances in the past where we’ve first heard of specific suspected clusters of illnesses through them,” Rima Khabbaz, the US Centres for Disease Control’s deputy director for infectious diseases, said of NGOs such as Samaritan’s Purse.

Michael Osterholm, the director of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, said in many parts of the world, such groups “are the safety net for global health. They are the ones in the areas of war and civil unrest.”

“The Ebola crisis was not a surprise to us at Samaritan’s Purse. We saw it coming back in April,” said Mr Isaacs last month. He added: “The international response to the disease has been a failure. If there was any one thing that needed to demonstrate a lack of attention of the international community on this crisis... it was the fact the international community was comfortable in allowing two relief agencies to provide all of the clinical care for Ebola victims in three countries.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks