Gorbachev: the model for the Obama doctrine

In the first of a series of articles marking his first 100 days, Rupert Cornwell assesses his foreign policy

Some already talk of an 'Obama Doctrine'. Others, sensing that everything may end in tears, compare him to Mikhail Gorbachev, who set out to change the image of Communism and ended up by destroying Communism itself. One thing however is incontestable. Barack Obama has set a new imprint on his country's foreign policy – and far more quickly than the last Soviet leader ever did.

Mr Gorbachev had been in power for 18 months before the "new thinking" and "perestroika" got under way in earnest in 1986. By contrast, Mr Obama still has a week left of his first 100 days in office, by which a new American president is judged, and his approach is visible everywhere.

The changes have been breathtaking in their speed and scope. He has signalled readiness to talk to those two longstanding foes of the US, Iran and Cuba. He has announced a "reset" of relations with Russia, launching a new round of nuclear arms negotiations and even offering to quietly drop plans to install missile defence units in central Europe, a plan Moscow detests, in return for Russian help in getting Iran to halt its uranium enrichment programme.

He has held a civil conversation with Venezuela's Hugo Chavez, arch "Yanqui"-baiter and troublemaker of Latin America. He has admitted to the Europeans that, yes, a lack of regulation of US financial markets was largely responsible for the global credit crisis.

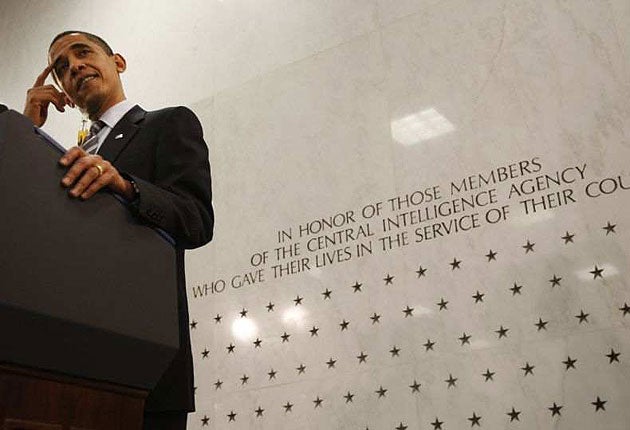

He has shut down the CIA's ghost camps and ordered the publication in their virtual entirety of memos that set out in minute detail the "enhanced interrogation techniques" – i.e. torture – authorised by the previous administration of George Bush.

He has pledged a new drive for peace in the Middle East, that by all indications would involve a two-state solution for the Israel/Palestine conflict, and a deal between Israel and Syria that would return to the latter the Golan Heights. He has taken action on greenhouse gases and climate change that would have been unthinkable under Mr Bush. The world is still rubbing its eyes.

Indeed, in terms of style there is already an Obama Doctrine: of coming across as being as different from his predecessor as can be imagined.

"I have come to listen," the 44th President said on his first trip to Europe last month, a trip that included both G20 and Nato summits, forums in which the US would have previously sought to lay down the law. Listening was never a quality attributed to Mr Bush.

To a large degree this more respectful approach reflects Mr Obama's unusual background. The first President from a racial minority, the first to have lived in another country (and Muslim Indonesia to boot), he can instinctively understand how other countries see the US in a way that his predecessors – even that super-quick study Bill Clinton – never could.

But it also reflects Mr Obama's personality. Pragmatism is his trademark, and the quality he is said to prize most highly in those around him. You see it in the cool and measured thoughtfulness with which he articulates policy. Mr Obama is a realist, who surely agrees wholeheartedly with that classic definition of madness: continuing to do the same thing and expecting a different result.

Thus, in particular, the change in strategy towards Cuba and the gra-dual abandonment of a policy that had stood unchanged for half a century. That policy, as any realist can see, is no nearer than it was in the early 1960s to delivering its objective of toppling the Castro regime. In other words, if it's broke, fix it.

Last weekend's Summit of the Americas provided another fine example of Obama realism, this time in response to the howls of outrage from the right back at home over his meeting with Mr Chavez. Venezuela, he noted when a reporter raised the issue, had a defence budget that was "probably one-600th of that of the US". It was therefore "unlikely that as a consequence of me shaking hands or having a polite conversation with Mr Chavez that we are endangering the strategic interests of the United States". The language was vintage Obama, dry and faintly mocking. Its subtext might have been, why can't we all grow up?

But growing up is not easy. Even many Republicans admit that Mr Bush's unilateralist, "either with us or against us" approach, which was especially visible in his first term, had been counterproductive and that the damage inflicted on America's moral standing by Abu Ghraib and the like had to be made good.

Go too far in the other direction however, and sweet reason can be seen as a sign of weakness. That was the error of Mr Gorbachev. For the first time, the Soviet Union had a leader who did not inspire fear. His own citizens despised him for it; those of its client states rejoiced and broke free.

America of course does not have an authoritarian system of government, built upon fear. Even so, admission of error clashes with a widespread assumption that America is somehow "better" than other countries. History's great powers have rarely been comfortable apologising for their behaviour. The US, where the doctrine of American exceptionalism still burns bright, is no exception. More important (and more pragmatically), the Obama approach may not work. On the streets of Europe, the crowds were cheering. But in the conference chambers, Europe's governments balked at the new President's demands for a global stimulus package and for more troops to fight the Taliban in Afghanistan.

The Russians quickly shot down the trial balloon of a trade-off between missile defence and Iran. And Iran responded to US signals of closer diplomatic engagement by hauling the Iranian-American journalist Roxana Saberi before a one-day kangaroo court and sentencing her to eight years in prison for being a spy.

As Lord Palmerston, among others, pointed out, countries do not have permanent friends, only permanent interests. Foreign powers may admire Mr Obama, but they will not let that affection blind them to their own interests – and the same is true in reverse. Better relations with friend and foe alike are desirable. But what will happens when the Obama doctrine of sweet reason collides with the American national interest?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks