The shocking truth about Guantanamo: they knew they had the wrong people

In the panic after 9/11, the US swept hundreds of men into Guantánamo – most not terrorists at all – and built a system that could not admit its own failure, writes human rights lawyer Eric Lewis in this extract from his new book

The long odyssey of the Guantanamo detainees was precipitated by the reaction of the United States to September 11, 2001. The Bush Administration launched an assault on Afghanistan beginning around four weeks later, on October 7. Osama bin Laden had maintained his headquarters in Afghanistan after his Saudi citizenship had been revoked; he had spent four to five years in Sudan before returning to Afghanistan in 1996. No one knew where he was, but to hunt down this one man and his few hundred fighters, the United States invaded a vast, mountainous land of 27 million people, known as the graveyard of empires after all those for centuries had tried and failed to subdue it. It would be another decade before Bin Laden was located and killed, not in Afghanistan but in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

The United States and its proxies grabbed anyone they could find on the Afghan-Pakistan frontier, generally men of Arab descent. The vast majority were not captured on an active battlefield but handed over by Afghans or Pakistanis for $5,000 or more in bounties, equivalent to two years’ average earnings in that impoverished border area. The United States Government dropped thousands of leaflets advertising the bounty program.

One flyer read: “Get wealth and power beyond your dreams. You can receive millions of dollars helping the anti-Taliban forces catch al-Qaida and Taliban murderers. This is enough to take care of your family, your village, your tribe for the rest of your life.”

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said that leaflets fell over Afghanistan “like snowflakes in December in Chicago.” Not surprisingly, Afghans eagerly rounded up foreigners and the United States eagerly accepted them without any real scrutiny.

The United States desperately needed to find terrorists in those panicked post-9/11 days. It had to show it was fighting back. It needed to demonstrate that it was making tangible progress in the “Global War on Terror.” It did not know who it had captured, and it seemed to not much care. The idea seemed to be to torture everybody and see what intelligence could be collected. There was much torture in those days, but very little actionable intelligence.

Within the first few weeks, the senior general in charge of the Joint Task Force admitted that “the major portion of his prisoners were not particularly dangerous or hardened terrorists” and a senior Marine intelligence officer concluded that the largest group “had nothing of substance to offer and should not have been there at all.” A senior Army intelligence officer formed the view by the spring of 2002 that “we’re not getting anything because there might not be anything to get.” Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, Chief of Staff to then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, filed a remarkable declaration in court stating his conclusion that:

“[A]s early as August 2002, and probably earlier to other State Department personnel who were focused on these issues, many of the prisoners detained at Guantánamo had been taken into custody without regard to whether they were truly enemy combatants, or in fact whether many of them were enemies at all. I soon realized from my conversations with military colleagues as well as foreign service officers in the field that many of the detainees were, in fact, victims of incompetent battlefield vetting. There was no meaningful way to determine whether they were terrorists, Taliban, or simply innocent civilians picked up on a very confused battlefield or in the territory of another state such as Pakistan.”

A confidential report prepared by the CIA as early as October 2002 concluded that most of the detainees did not belong there. Major General Jay Hood, a former Guantanamo commander, conceded, “Sometimes we just didn’t get the right folks,” and despite knowledge that the bulk of the detainees had no involvement in terrorism or intelligence to offer, Hood said that they were not released because “nobody wants to be the one who signs the papers.” The deputy commander, Brigadier General Marin Lucenti, stated that these men “weren’t fighting,” they “were running.”

Despite the open secret early on that the detention dragnet had yielded virtually nothing of value, bureaucratic fear and inertia and profound indifference to the lives of these men, whose culture, religion and language were alien to their captors, meant that they remained detained and abused. Secretary of State Rumsfeld wanted actionable intelligence, and the interrogations continued as the Pentagon ratcheted up the abusive tactics against men who had nothing to say.

The United States could not and would not accept what quickly became obvious: that it had brought to Guantanamo hundreds of men, many of whom were following a long-standing tradition in the Gulf of going to perform charitable work in poor Muslim lands. Afghanistan was a war-torn country with massive drought, population dislocation and lack of access to food, water and health care. It was subject of global aid programs on a massive scale. Many of these men would go for a few weeks each year, generally on annual vacation, and many had been doing so long before anyone had heard of Osama Bin Laden or Al Qaida. Islamic charities had established programs working in conjunction with American and international NGO’s. Others were traders or students. The United States would not believe that most of these men simply happened to be in Afghanistan or Pakistan after the United States began bombing in October 2001. Hundreds of these men, wanting no part in a war against a superpower, fled and tried to find safe haven in Pakistan and return home.

Torture in Afghanistan, in the dark prisons and at Guantanamo was endemic and approved at the highest levels, including by the Secretary of Defense, top generals, a future head of the Central Intelligence Agency, who supervised a dark prison in Thailand, and many others. The High Value Detainees — some of whom were likely architects of 9/11 — were elsewhere for at least four years after the hundreds of traders, teachers, preachers, project builders or low-level soldiers were first picked up on the Afghan-Pakistan border. The abuse was not only shameful; it was senseless and deeply counterproductive to US interests and moral authority. It still is.

None of the men who began arriving in early 2002 had anything to do with 9/11, but it did not matter. Donald Rumsfeld had declared the men at Guantanamo the “worst of the worst” and the guards there were indoctrinated with this view and generally treated detainees accordingly. Some of the guards had served at sites that were hit on 9/11, and they were sent to Guantanamo to confront the men they were being told were responsible for the death of their comrades.

Rumsfeld and the defense and intelligence agencies at the highest level knew surprisingly early on they were not holding the architects or implementers of 9/11, but that was not the message that the President, the Vice President or the people of the United States wanted to hear or that Rumsfeld was inclined to communicate. The truth took second place to the construction of the post-9/11 narrative. The President could not say, “Well, we have bought and paid billions of dollars for an assortment of Uighur merchants, teachers of Arabic, prayer leaders, mosque builders, well diggers and the occasional barely trained soldier who had been shown how to fire a Kalashnikov for an afternoon.” Perhaps there was a driver or a messenger or a cook for Al Qaida. But no one who mattered had been sent to Guantanamo during the first four years and the Bush Administration knew it. The United States had come up empty, but no one would admit it.

Guantanamo was chosen to be a “legal black hole,” a place controlled by the United States but not in the United States, where these men were to be interrogated and held without process. President Bush promptly declared that the Geneva Conventions did not apply at Guantanamo Bay, a first chink in the wall of the rule of law. This had never happened before. While violations of the Conventions had certainly occurred, no American leader had openly stated the United States had no obligation to follow them. In giving legal approval to the authorization to ignore the Geneva Conventions just as the detainees were arriving at Guantanamo, White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales said, “the war against terrorism is a new kind of war” and “this new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva’s strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners and renders quaint some of its provisions.”

Common Article Three of the Conventions, added after the horrors of the Second World War, prohibits “cruel treatment and torture [and] outrages to dignity.” Now, a half-century later, a moral consensus borne of the traumas of the twentieth century was viewed as somehow outmoded sentimentalism. The purported “new paradigm” of the Global War on Terror would be much like a very old paradigm; as Vice President Cheney stated, aided by the twisted logic of compliant lawyers, Al Qaida required the United States to “take off the gloves.”

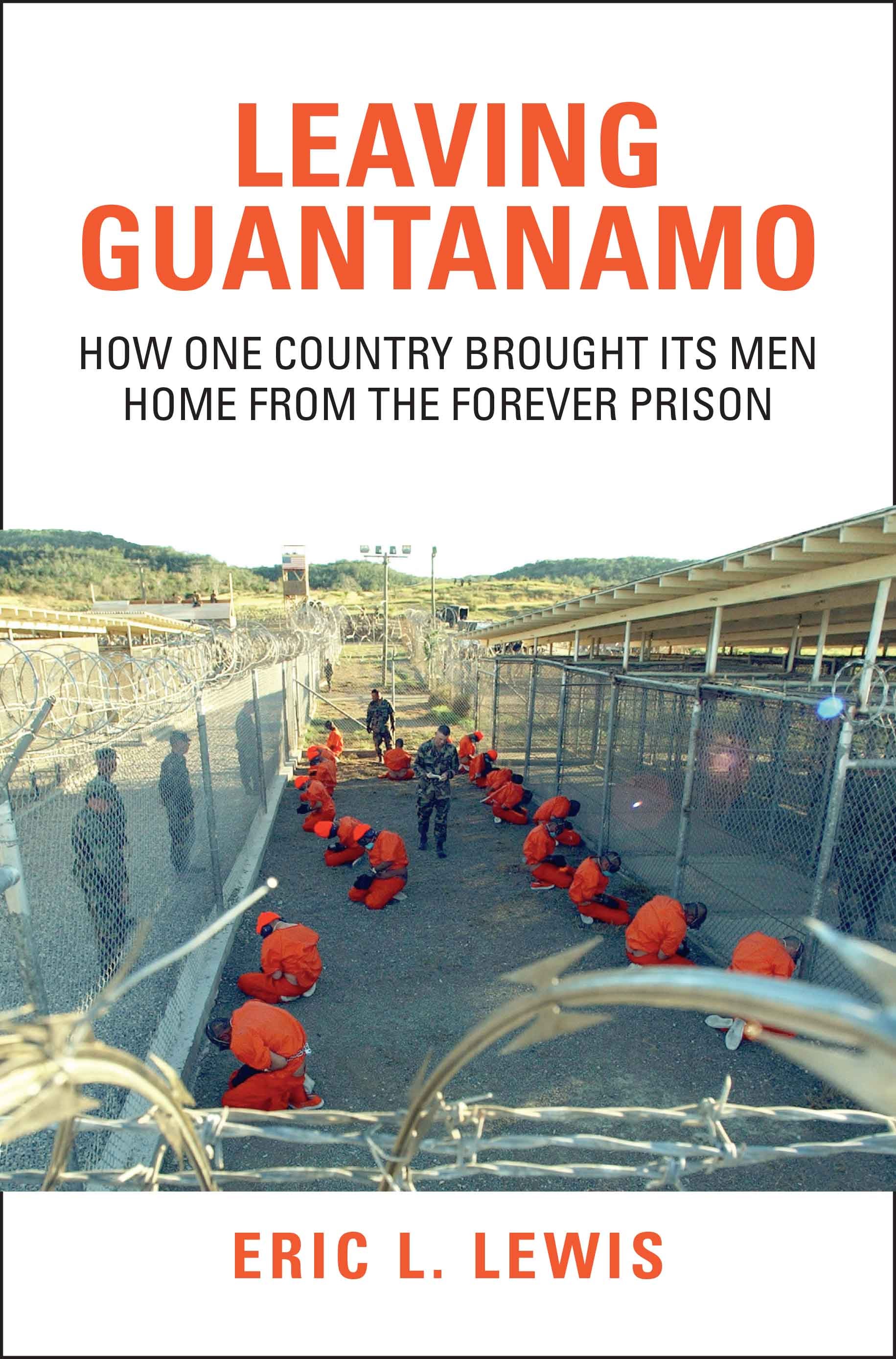

‘Leaving Guantanamo: How One Country Brought Home Its Men from the Forever Prison’ is published by Cambridge University Press. Eric Lewis is a human rights lawyer and also sits on the board of directors of The Independent

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks