Presidents’ Day 2020: What Donald Trump and George Washington could learn from each other

National holiday honours Revolutionary War hero turned first leader of the republic

Presidents’ Day is an American national holiday held on the third Monday of February every year.

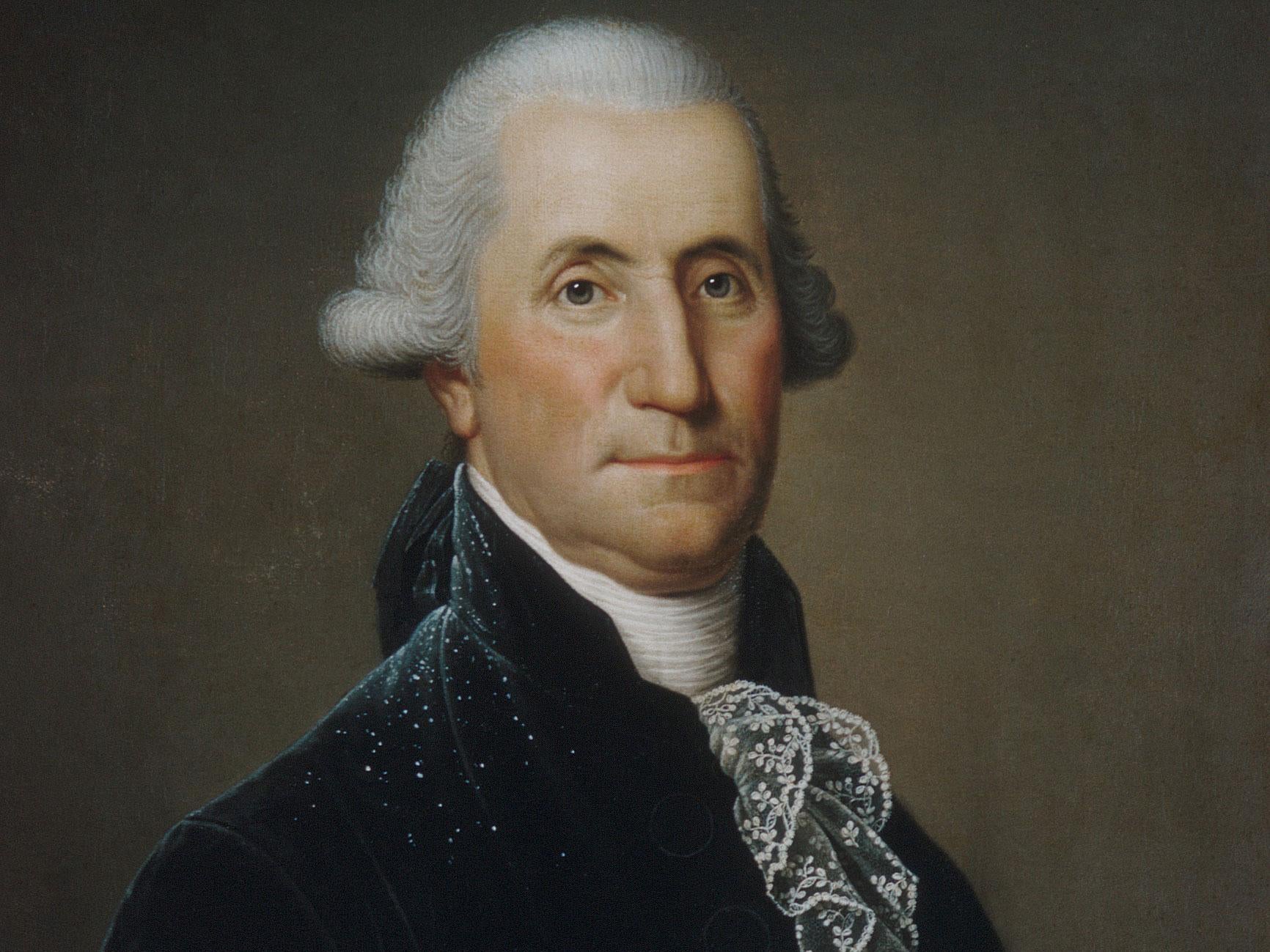

The date is set aside to honour the first president of the republic George Washington, born on 22 February, 1732 in Virginia.

Abraham Lincoln, the country’s 16th president, was also born in the same month and the three-day weekend has likewise cheered his memory every year since Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act under Lyndon Johnson in 1968.

But the day is popularly thought of as “Washington’s Birthday” and it is the Founding Father who casts the longest shadow over the nation’s history.

What lessons might America’s first president have for the 45th?

Washington’s Farewell Address to the nation towards the end of his second term in 1796 is one of his most famous contributions to the nation’s heritage and bears revisiting in the age of Trump.

The 7,641-word document had originally been drafted for the former Revolutionary War general by James Madison four years earlier when he feared dying in office, beset by rheumatism and dental pain.

It was never used, as events returned the president’s thoughts to the problems of the fledgling nation, but he eventually came to revisit it as he dreamed of retiring to his plantation home, Mount Vernon, handing Madison’s draft on to Alexander Hamilton, architect of the Constitution and his former Treasury secretary, to make revisions and amendments.

Washington and Hamilton drastically reworked it and their finished version would take the form of an open letter to the American people, first published in the Philadelphia newspaper The Daily American Advertiser on 19 September, 1796.

In it, the president stressed the importance of national unity, urging his fellow citizens to put aside their personal differences and grievances for the greater good.

“You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together,” he wrote. “The Independence and Liberty you possess are the work of joint counsels, and joint efforts, of common dangers, sufferings, and successes.”

“Your Union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty and... the love of the one ought to endear you to the preservation of the other.”

The letter also declared that the worst enemy of government was petty factionalism: loyalty to party over country.

Allowing a “spirit of revenge” to motivate representatives of the people would only lead to the ascension of “cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men”, who would “usurp for themselves the reins of government; destroying afterwards the very engines, which have lifted them to unjust dominion.”

Finally, Washington – writing in the immediate wake of the French Revolution – warned against the threat posed by “foreign influence and corruption.”

While fully supportive of friendly diplomatic and commercial ties with other nations, the president cautioned that “inveterate antipathies against particular Nations, and passionate attachments for others, should be excluded”.

The 44th man to succeed Washington – Donald J Trump – was recently acquitted by a Republican-majority Senate after being impeached for attempting to pressure Ukraine into launching a bogus anti-corruption investigation into his own domestic political rival, Joe Biden.

In exchange for the release of $391m (£302m) in congressionally-approved military aid he had withheld, Trump hoped to secure an advantage ahead of the 2020 presidential election by smearing his opponent’s reputation.

But the intervention of a patriotic CIA whistleblower who overheard his “perfect” call with Volodymyr Zelensky saw the House commence an investigation that resulted in the president being charged with twin articles of impeachment: abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.

Donald Trump had ignored all three of Washington’s strictures – encouraging partisan division, urging his party to support him at all costs and flagrantly inviting foreign interference in American affairs – and was frankly and appropriately admonished by the chamber for his actions.

What lessons might Trump have for Washington?

You might think the current president, a blustering Manhattan property mogul with a taste for hamburgers and gold signage, might have had little to say to his forefather, an eighteenth century planter’s son turned freedom fighter.

Trump did compare himself to Washington in a cabinet meeting in October last year, claiming that the Founding Father had sought to profit from his presidency just as he has and kept both “a presidential desk and a business desk”. This was, unsurprisingly, completely untrue.

A Monmouth University poll in December picked up the idea and asked voters who was the superior leader: among general voters, Washington won with 71 per cent of the vote with Trump on 15 per cent. Among Republicans, it was much closer: 44 per cent to 37 per cent.

It’s certainly clear that Trump himself has little reverence for history, so much so that he was entirely ignorant of what took place at Pearl Harbor until his then-chief of staff John Kelly explained it to him during a tour of the USS Arizona Memorial in Hawaii in 2017, according to Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig's recent book A Very Stable Genius.

But that has not stopped the luxury property magnate presuming to give his revered predecessor advice once before.

As Politico reported last year, the president and first lady took their French counterparts Emmanuel Macron and Brigitte Macron to visit Mount Vernon in April 2018.

The quartet toured the historic compound in Virginia guided through its house and grounds by the facility’s chief executive, Doug Bradburn, who gave them a 45-minute lecture on the Founding Father’s life and achievements but struggled to hold Trump’s interest on any subject other than the extent of Washington’s wealth for any length of time.

“If he was smart, he would’ve put his name on it,” Trump reportedly reflected of the property afterwards.

“You’ve got to put your name on stuff or no one remembers you.”

When Bradburn pointed out that Washington had succeeded in having a state and the nation’s capital named in his honoured, Trump laughed and said: “Good point”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks