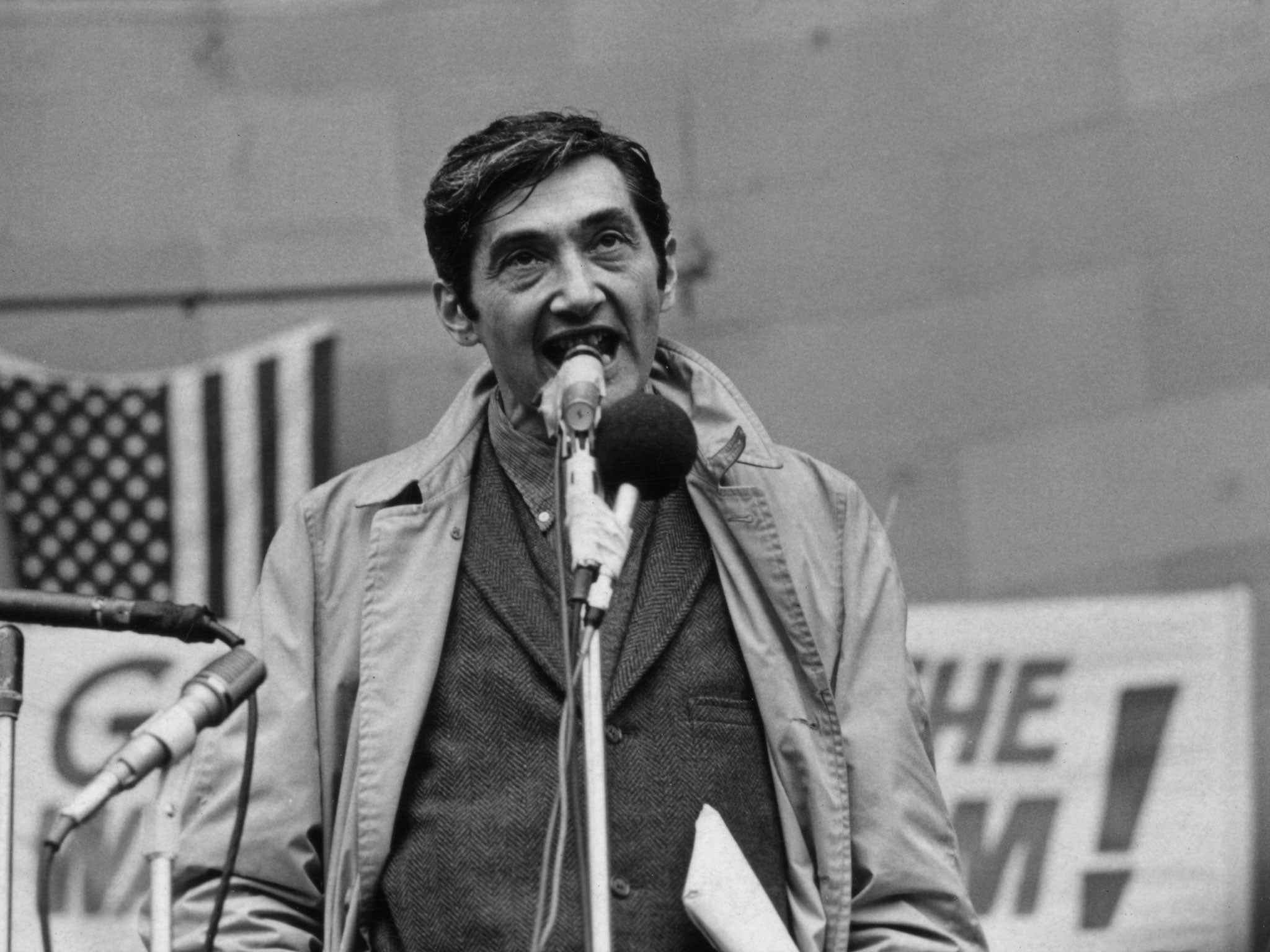

Pacifist priest who led protests against Vietnam war dies aged 94

Berrigan spent years at loggerheads with his government and the Roman Catholic Church

A longtime peace activist whose repeated acts of civil disobedience made him a major figure in the radical left of the 1960s and 70s, has died.

The Rev Daniel J Berrigan, a writer and teacher, who spent years at loggerheads with his government and the Roman Catholic Church, died on 30 April at a Jesuit residence at Fordham University in the Bronx, aged 94.

The cause was a cardiovascular ailment, said the Rev James Yannarell, a priest affiliated with the Fordham Jesuit community.

In May 1968, Father Berrigan, his brother and fellow priest Philip Berrigan, and seven other activists entered a Selective Service office in Catonsville, Maryland.

They gathered hundreds of draft files, lugged them outside and, with a recipe of kerosene and soap chips taken from a Green Berets handbook, burned them to ashes. “The Catonsville Nine”, as they became known, were arrested, and in a five-day trial in October 1968, they were found guilty of destruction of government property.

Father Berrigan wrote a play about the event, The Trial of the Catonsville Nine.

“Our apologies, good friends,” he wrote, “for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.”

The judge sentenced Father Berrigan, then 47, to three years in federal prison. Philip Berrigan, who had been charged in earlier protests, received a longer sentence.

In 1970, after the appeals ran out, Father Berrigan refused orders to report to federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut. He went underground, on the lam from safe house to safe house, and spent four months dodging an FBI manhunt. After many false leads, he was caught on Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island. Days before he was captured, he spoke at a church in Germantown, Philadelphia, saying, “We have chosen to be branded peace criminals by war criminals.” He ultimately served two years in prison.

Father Berrigan was a willing recidivist who was first arrested in 1967. His rap sheet would eventually be filled with arrests and convictions from protests at weapons laboratories and at the Pentagon.

Daniel Joseph Berrigan was born May 9, 1921, in Virginia, Minnesota, the fifth of six sons of a pro-union father and a mother who opened her home to the poor.

In 1939, Daniel Berrigan entered the former St. Andrew-on-the-Hudson Jesuit novitiate near Poughkeepsie, New York. During his years of theological training, he wrote poetry and taught at Catholic high schools, preparing for a career of teaching or pastoring. He was ordained in 1952.

In the mid-1950s, he taught at Brooklyn Preparatory High School in New York. From 1957 to 1962, he taught theology at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York.

Over the decades, Father Berrigan’s forays into the academy also included stints at Cornell University, the University of Detroit, Loyola University New Orleans, DePaul University and the University of California at Berkeley. During the Vietnam War years and after, he believed that universities had become tools of the government, military and corporate giants.

With no conventional ministry, Father Berrigan operated for more than 40 years out of a small commune known as the West Side Jesuit Community on West 98th Street in Manhattan. He aligned himself with Dorothy Day and the pacifist Catholic Worker movement and formed a friendship with Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk who was also moving away from conventional priestly piety by condemning US involvement in Vietnam.

In 1968, Father Berrigan traveled with Howard Zinn, the liberal political activist and historian, to North Vietnam in a successful effort to bring back three captured US pilots. Father Berrigan was affiliated with several Catholic antiwar groups and later ministered to AIDS patients.

In 1980, he and his brother Philip were instrumental in forming the Plowshares Movement, a loose coalition of pacifists who were often arrested for acts of civil disobedience at military bases and other sites, including a nuclear-missile facility in Pennsylvania.

Among those jailed was actor Martin Sheen, who once said, “Mother Teresa drove me back to Catholicism, but Daniel Berrigan keeps me there.”

In 1965, Cardinal Francis Spellman, a supporter of the Vietnam War, told Father Berrigan’s Jesuit superiors to get the agitator out of New York City. He was sent to South America, but seeing the conditions in the slums of Peru and Brazil made him more militant, not less. He believed that the Catholic Church too often sided with the rich, and he criticized a US foreign policy that included the sale of weapons to rightist military regimes.

Father Berrigan took aim at his fellow Jesuits when he wrote his Ten Commandments for the Long Haul (1981).

“The Jesuits are masters of invention,” he wrote in his provocative manifesto. “They come out of the culture, they know how to take its pulse, try its winds and trim their sails. Nothing extravagant, nothing ahead of its time, nothing too fast. Consensus! Consensus!”

Father Berrigan wrote more than 40 books, including a 1987 autobiography, To Dwell in Peace, He wrote numerous volumes of poetry, including Time Without Number (1957), which won the Lamont Poetry Award, and Prison Poems (1973).

His brother Philip died in 2002. Survivors include a sister.

In a 2008 interview in The Nation magazine, Father Berrigan echoed a line of Mother Teresa’s that spiritual people should be more concerned about being faithful than being successful.

“The good is to be done because it is good, not because it goes somewhere,” he said. “I believe if it is done in that spirit it will go somewhere, but I don’t know where. I have never been seriously interested in the outcome. I was interested in trying to do it humanely and carefully and nonviolently and let it go.”

The Washington Post ©

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks