The awards ceremony that lays bare American healthcare’s worst abuses

Named for infamous ‘pharma bro’ Martin Shkreli, a former hedge fund manager who acquired a pharmaceuticals company and then raised the price of a generic drug by 5,000 per cent overnight, the awards reveal a system rife with moral compromise. Holly Baxter reports

Every December, The Lown Institute, a nonpartisan healthcare think tank, holds an awards ceremony. The recipients are unlikely to attend. Their work is more likely to inspire shock and horror than applause and adulation. And the namesake of the ceremony is one of the most publicly reviled figures of the past decade.

The Shkreli Awards — named for the infamous “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli, a former hedge fund manager who acquired a pharmaceuticals company and then raised the price of a generic drug used to treat malaria and in AIDS protocols by 5,000 per cent overnight — don’t showcase health innovation, or medical breakthroughs.

Instead, they showcase the worst abuses of the American healthcare system: a hospital that told a comatose patient’s family they’d ship her out of the country if they didn’t start paying them $500 per day; surgeons who encouraged experimental, risky surgery on low-income patients of color in order to earn compensation from a medical device company; hospitals that wheeled homeless patients outside and dumped them onto the sidewalk, still dressed in their medical gowns; an OB-GYN who sexually assaulted patients for over 20 years while the university he worked at ignored escalating complaints against him; the controversial business of encouraging babies to have “tongue ties” cut unnecessarily; an infant who went into severe respiratory distress not long after open-heart surgery but whose insurance refused to cover the emergency air ambulance to hospital, saddling the parents with a $100,000 debt.

The cases that have “won” these awards detail almost everything that can go wrong in the U.S. healthcare system. From predatory practices at the insurance level to CEOs who decimated community hospitals in the pursuit of profit, to doctors incentivized to over-diagnose or over-prescribe, to healthcare centers refusing to provide life-saving treatment to poorer patients.

And it’s a situation, says Dr. Vikas Saini, that is getting “worse and worse”. Saini is the president of the Lown Institute and a clinical cardiologist trained at Harvard by the institute’s namesake, Bernard Lown, a Nobel Peace Prize winner and life-long social justice advocate. Of his many jobs, judging the Shkreli Awards is the one that Saini finds the most emotionally taxing.

“As a physician, the behavior of the physicians strikes a deep, deep chord,” Saini says. Although there are some more objectively shocking stories, one where a heart doctor placed coronary stents in people’s arteries for no good reason has stayed with him.

“I find that very, very upsetting personally because I’m a cardiologist,” he adds. “I’m not sure it’s necessarily the most striking or shocking ever [example], but that’s the one that speaks to me the most.”

In Saini’s view, medicine is as much an art as it is a science — and it is this intimacy, this reliance on trust, that makes its abuse so morally corrosive. “I don't think the public understands the number of things we do that are discretionary, where the evidence could go either way — maybe it works, maybe it doesn't,” he says. “There's a lot more of that than I think the public understands… That's why in general, there's such leeway and such discretion, and I think you need some moral underpinnings to help you.” Without a firm ethical framework, medicine risks becoming a money game, with the patient reduced to a pawn. In a profession defined by discretion, the opportunities for corruption are everywhere.

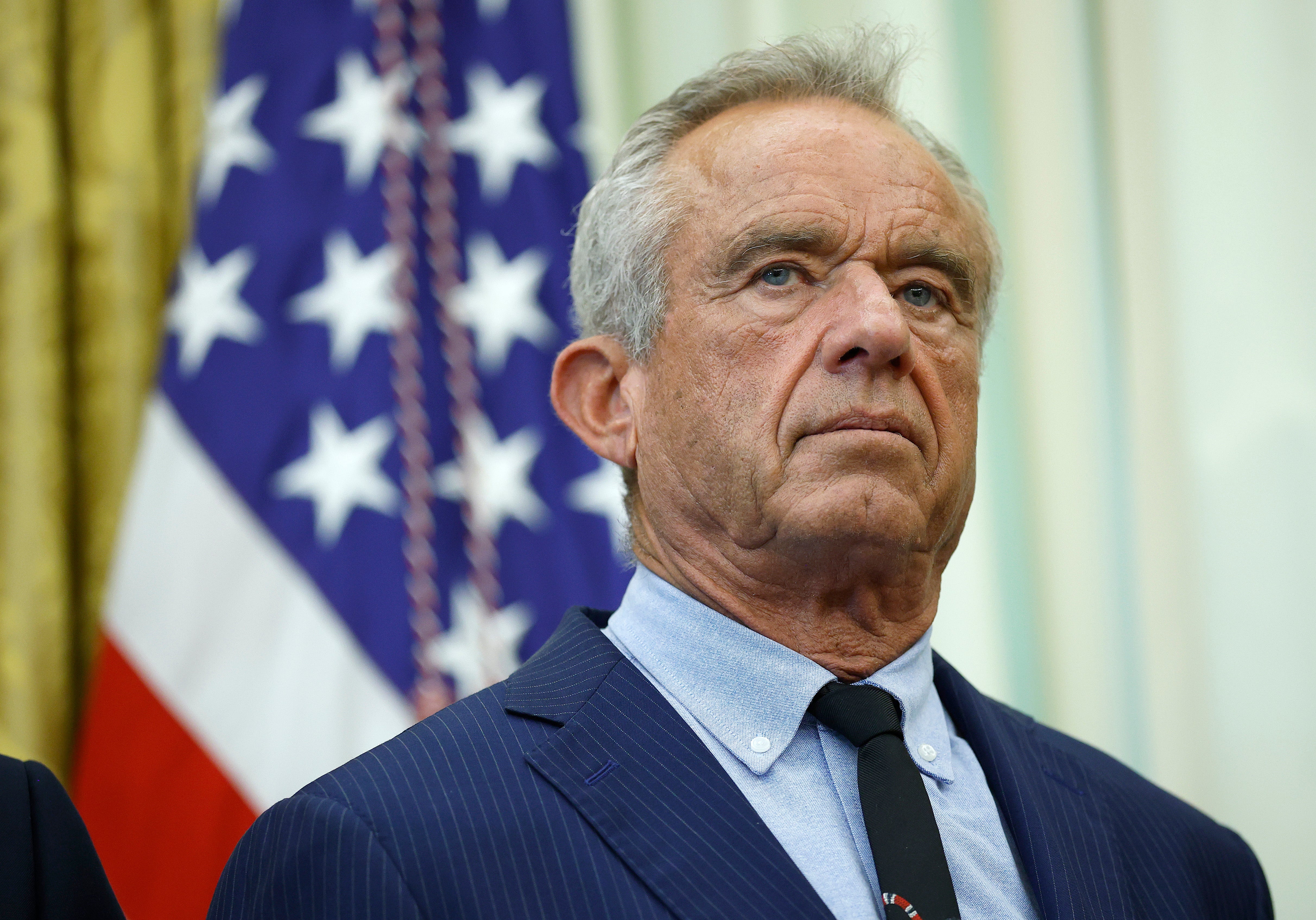

And therein lies an uncomfortable truth: RFK Jr., anti-vaxxer conspiracies, and an anti-science movement disguised as “wellness” didn’t come from nowhere. Few healthcare systems have been as volatile or as politically fraught as in America. Within the space of a single year, a health insurance CEO was shot dead by a disgruntled patient, while a Health and Human Services Secretary with no medical training fired the CDC’s entire vaccine advisory board shortly after taking office. If nothing else, these events testify to a system under deep strain.

Skepticism toward long-established public health measures such as vaccination has been deeply damaging. It has helped usher in the return of polio, three decades after its eradication in the US, and led to the first death of a child from measles in a decade. But distrust toward doctors and pharmaceutical companies has been building for almost a century.

Black Americans, for example, are more likely than white Americans to express vaccine hesitancy — a disparity that was especially visible during the pandemic rollout. Research suggests this reflects lived experience as much as ideology: Black patients are more likely to report negative interactions with doctors, while Black women are more likely than any other group to have their pain and health concerns dismissed, and they are three times more likely to die in childbirth than their white counterparts. Layered onto this is a legacy of medical abuse and dismissal, including the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Add to this the fact that women of all races worldwide wait years longer for diagnosis of a range of health conditions, from cancer to heart disease, and it’s clear that suspicion toward mainstream healthcare institutions has had reason to exist long before Facebook conspiracies and the notorious “crunchy-to-alt-right pipeline”.

“What we see in the [Shkreli] Awards is that the chasing of money is kind of endemic and ubiquitous in the American healthcare system,” says Saini. “...Now, there's always a tendency to have a fantasy of a golden age, and I don't expect or believe that there was ever a real golden age. But it is true, I think, that the degree of aggressiveness with which people are chasing the money has accentuated in the last decade or two.”

Saini believes that people who think healthcare runs best as a privatized, competitive marketplace are making a “fundamental error in logic”.

“I think almost anybody, when they take off all their different social masks and they're just quiet with themselves as a human being, I think everyone understands that… healthcare is very different,” he says. He’s spoken to a lot of people during his career who think that the solution to the healthcare situation in America is more privatization; that a Reagan-style “magic of the marketplace” will happen if red tape is slashed, and high prices will come down while care would get better.

“As much as I understand that logic, I would just submit that I think it's incorrect,” he says. “Because just as there are no atheists in foxholes, similarly, I don't think there are a whole lot of capitalists when they or their family are seriously sick. I think people just want to be taken care of, and they want to be able to afford it, and they want to not have to think about it. They certainly don't want to go around shopping as if they were buying a car.”

How to change a broken system

Can the system be changed — and if so, how? Saini argues that change is inevitable, because the current system not only permits corruption but actively incentivizes it. Certainly, there are genuinely malicious cases of malpractice, the kind lampooned by the Shkreli Awards. But, as he puts it, “the vast majority are not as explicitly bad as that.” More often, he says, “the vast majority are tales they tell themselves and data that they skew to justify it.”

People are corruptible; doctors are no exception. And in a system that exerts pressure from every direction — from TV ads for cancer drugs and promotions in medical trade magazines, to pharmaceutical-funded conferences, financial incentives, and a culture that rewards unnecessary tests or even surgeries if patients demand them — it is hardly surprising that bad actors emerge. More unsettling still is how often the system produces something worse: well-intentioned professionals who have convinced themselves that their bad actions are justified, and beyond reproach.

“It will take a movement of people” to change the system for good, Saini says. “It will take organized effort. And I'm sorry to say, it'll probably require pressure from outside of the healthcare industry because the status quo is serving too many people. There's still enough people who are really doing very well and are not going to want to rock the boat that it is going to take some kind of… externality, I think.”

He doesn’t think it will be Bernie Sanders-style Medicare for All, nor will it look like the Canadian universal healthcare system or Britain’s National Health Service. And he also doesn’t think the stars will align in the next few years, because politics has become so divisive that politicians are unlikely to work together to get something through. Most Republicans are fundamentally opposed to raising taxes and committed to the idea of allowing people a market-style “choice” about where they go and who they see (although, Saini notes, there is a certain irony in the right talking so incessantly about the importance of choice in healthcare while simultaneously legislating against a woman’s right to choose.)

Democrats are divided throughout the party, with the furthest left insistent about a single-payer system (“behavioral psychology tells us” that this probably won’t work, says Saini, because an electorate will never get on board with having something taken away) and the furthest right fully supportive of the status quo. Obamacare was the middle ground, but it hardly solved every issue — and Republicans have talked loudly about replacing it for decades.

Not that that talk has translated into anything. A little less than a decade ago, John Boehner, having recently stepped down as Republican Speaker of the House, reflected on why his party had failed to create an alternative to Obamacare, despite so many claims that they would.

"In the 25 years I served in the United States Congress, Republicans never, ever, one time, agreed on what a healthcare proposal should look like,” he said. “Not once."

Ideally, Saini says, a movement that changes healthcare in America will unite patients, community leaders and business leaders. All of them will need to be honest about the fact “that healthcare — how we pay for it, how we make serious decisions about it — is much too important to be left either to the industry itself or even to politicians.” The solution will have to involve entirely new structures, new formats and new overseers, as well as much improved affordability.

“It may sound utopian,” he says, “but I will say I’ve been thinking about this for a long, long time. I don’t see any other way.”

The Shkreli Awards are announced on December 11th

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks