‘I believe in redemption’: Inside the fight for religious rights in the execution room

Priests and pastors have been comforting the condemned for centuries — so why are states increasingly restricting access to the execution room? Josh Marcus writes

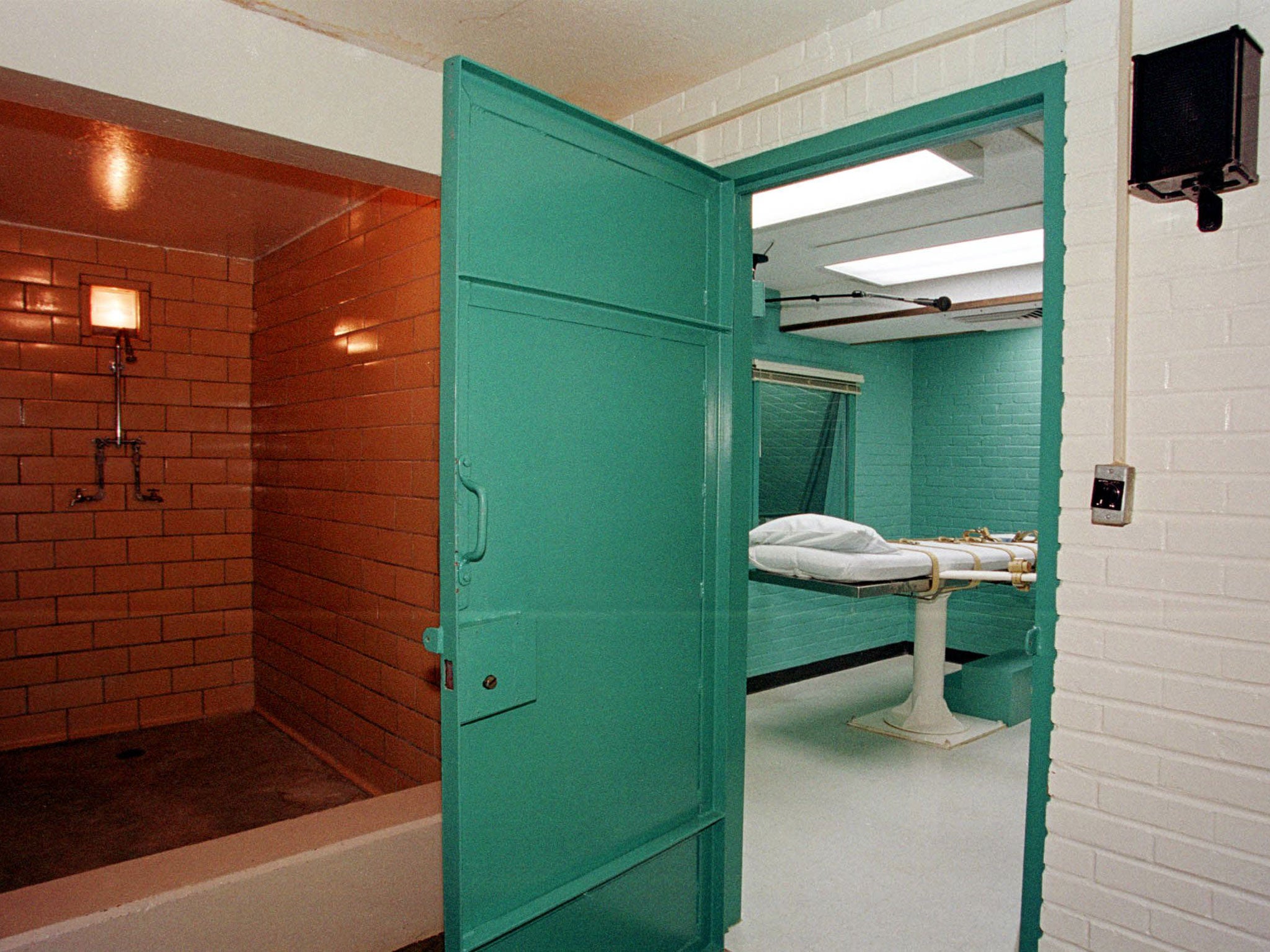

This fall, Alabama death row inmate Willie B Smith was strapped down onto a gurney, moments before receiving the lethal injection drugs that would be used to execute him, when he turned towards his pastor, Robert Wiley, with some unexpected words of encouragement.

“It was very interesting: here’s a man about to be executed, and he looks at me and asks if I’m alright,” Mr Wiley told The Independent. “I said, ‘I’m good, brother,’ and he was like, ‘Just stay up, keep your head up.’”

The comfort usually flowed in the other direction. The two had been speaking for about two years, often about God and the Bible, but sometimes about more earthly matters: how Smith longed to see the beach or the mountains before he died. How he missed the taste of a real cheeseburger.

Smith, who was intellectually disabled and had been in the middle of an ongoing disability rights lawsuit against the state, was executed on 21 October, but those words on the day of his death have stuck with Wiley, a Birmingham-based pastor. Wiley was well aware that the man he was ministering to had been convicted of horrible things: robbing, abducting, then shooting a woman named Sharma Ruth Johnson in the head, before putting her body in the trunk of a car and setting it on fire. And some people questioned why Wiley would spend his time working with a brutal killer.

"There’s no excuse for what he did. He never made any excuses about it,” Wiley said. “The details of the crime and everything, it’s atrocious.”

Still, he says the moment in the execution room is a reminder of just how important religious exercise is behind bars, and the kind of comfort it can grant people the state chooses to execute in their final moments.

“It also gives strength to just how far God had brought him in the end,” Wiley said. “I believe in redemption. Everyone has the right to repentance. In brother Willie’s case, he had been there almost 30 years. I could truly say that he wasn’t the same person when he was executed as when he was first convicted. He was a totally changed individual. It was the genuine article. He’s one of the most spiritual individuals that I’ve come to know.”

For Smith to even have a spiritual adviser in the execution room required a hard-fought legal battle that went all the way up to the Supreme Court. And the issues that were raised there in February, when the court sided with Smith and temporarily delayed his execution, aren’t going anywhere.

Beginning next week, the high court will explore this question in even finer detail in a case out of Texas: if prisoners have a right to religious counsel in their final moments, is it enough these advisers pray silently, or do the condemned deserve to hear prayers out loud and receive physical touch before they meet their maker.

On 9 November, the Supreme Court will take up the case of John Henry Ramirez. The Texas man was convicted of a gruesome 2004 murder, stabbing convenience store worker Pablo Castro 29 times while drunk and high, robbing him of a meagre $1.25. Unlike other high-profile death row inmates, Ramirez doesn’t claim he’s innocent. Rather, he argues that Texas prison policy, which doesn’t allow spiritual advisers in the execution chamber to vocally pray over inmates or touch them, is infringing on his statutorily and constitutionally protected religious rights.

“It would just be comforting,” he told The New York Times earlier this year, wondering what it is state officials fear would occur if he was given death rites in a normal manner.

“What will happen? I’ll have a true spiritual moment at the point of death and you don’t want me to have that?” he said. “You want to keep that from me, too?” State officials argue that the current policy still allows inmates to receive spiritual comfort, but that further intrusions of religion into the death room would disrupt the secure and orderly process.

The policy, found in the country’s single most prolific death penalty state, as well as one where faith is a regular and powerful force in politics, has inspired widespread condemnation.

“Touch is spiritually important. There’s something there,” Ramirez’s pastor Dana Moore told Christianity Today. “Jesus healed by touching. Jesus gathered the children in his arms; that’s touching. James talks about anointing people with oil; that’s going to involve a touch. So I said I wanted to touch him too.”

The two men have never shared physical contact. When they pray, a layer of glass separates their hands.

Full-throated prayer with an inmate before their execution is “one of the oldest religious freedom rights known to history and the Christian tradition,” The Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops and US Conference of Catholic Bishops argued in an amicus brief submitted ahead of oral arguments, one that both requires and has always featured touch and speech. The groups, representing the state and national leaders in the Catholic church, argue against capital punishment as a whole, but say if a state must go forward with executions, they should do so allowing the full practice of these rights.

“It represents a judgment by fallible human beings that a person is beyond redemption,” the organisations wrote. “That is a judgment the Catholic Church rejects. The state should act with justice by sparing Ramirez’s life. If it will not, it should allow him to seek the mercy of God at the moment of his death.”

A number of spiritual advisers who have counselled inmates during their state and federal executions, including noted death penalty activist Sister Helen Prejean, wrote a brief of their own in the case, saying their role “is not simply to stand by mutely, but to minister to the prisoner as he meets death, providing spiritual comfort and a final opportunity for the individual to engage with his faith at the most critical time.”

The state of Texas, which had allowed state-employed chaplains in the execution room until 2019, meanwhile argues that doing so now presents a security risk, and that Ramirez is merely trying to stall his killing. They also claim Ramirez’s suit relies on an overly broad interpretation of the religious protections embedded in the First Amendment and Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act. States don’t have to do everything an inmate wants, Texas attorney general Ken Paxton wrote in court documents; they just can’t force inmates into doing things that violate their religion. Plus, limits are inherent on death row. Texas wouldn’t bus an inmate to their church of choice, even if that was more in line with their faith wishes at their time of death.

“That a state may not impose policies coercing an inmate to do what his religious tenants forbid does not mean that it must accede to his every religious demand. By design, prisons impede inmates’ freedom to behave as they might wish, which, necessarily limits some of their religious behavior,” he argued, adding, “As in incarceration, restrictions are inherent in execution.”

Though it deals with an ancient set of practices, this question is a relatively recent one, legally speaking. Those set to be executed have been joined by clergy since America’s founding, when men facing the hangman’s noose would be read an “execution sermon.” The first known federal execution in 1790 involved a religious ceremony during the killing. Since then, various states as well as the federal government have allowed faith leaders access to the execution site to pray out loud and touch those sentenced to death. In Texas, between 1982 and 2019, chaplains were present at nearly 600 executions. Even Nazi war criminals, executed at military tribunals overseen by the US Army, received prayers out loud before being dropped through a trap door and hanged.

Things began to shift in 2019. In February of that year, the Supreme Court heard the case of Domineque Ray, an Alabama death row inmate who argued his religious rights were being violated because his imam couldn’t join him in the execution room, even though state-employed Christian prison chaplains were allowed to pray directly over inmates.

“Alabama was allowing them [spiritual advisers] to be in the cell, the holding cell, before going to the execution chamber, a place where the lawyers were not allowed to go, but then they said, ‘Oh, it’s time for the execution, you have to go back to the visiting room,’” said John Palombi, Ray’s public defender. “They were taking away the spiritual adviser at the point where they were needed the most.”

The court allowed the execution to proceed, holding that Ray had challenged the execution conditions too late, but the decision came in for heavy criticism from the liberal Justices, as well as rights groups. Justice Elena Kagan called the decision “profoundly wrong,” and the state soon banned all spiritual advisers from being inside executions.

“That was their solution,” Mr Palombi said. “‘Oh, you say we’re discriminating against non-Christians? We’re just going to not do it for anybody.’ That was their solution.” (The state wouldn’t change course until Willie Smith sued to have his pastor by his side, and the court agreed.)

Just months after the 2019 Domineque Ray case, the Supreme Court heard a similar suit from Texas, concerning the fate of Patrick Murphy, a member of the infamous “Texas Seven,” who had escaped prison and been part of the murder of a police officer in 2000. The state had Christian and Muslim chaplains it allowed into executions, but Murphy is Buddhist, and the high court has stayed his execution until he could be allowed his own spiritual advisor.

Less than a week later, the state took a similar course to Alabama, and banned all prison chaplains from the execution room, until it changed course just this April to re-allow them in the chambers following the Willie Smith decision. Now it’s up to the high court to decide whether the new policy does enough to protect religious rights to avoid being struck down.

Palombi, the public defender, is a veteran of capital cases, and worked on both Domineque Ray and Willie Smith’s cases. He’s used to people questioning why death row inmates, convicted of the worst crimes imaginable, deserve such care and attention to their spiritual lives. But he says this dichotomy is the point.

“The system should be better than them. The system should be proving this,” he said. “If society is enacting the ultimate punishment on someone, having them at the moment of that death, having their religious beliefs affirmed and being allowed to exercise them is important for the society, not just for the individual.” In 2018, contemplating his eventual execution, Ramirez wrote a poem that included these lines:

Comfort me like a hug

while I await the final tug.

Of this noose around my collar

will you notice when I holler?

Whatever happens to Ramirez, he will have a spiritual adviser present at the execution as a whole, in one manner or another. The ultimate goal, of course, is for his pastor to pray over him as he leaves Earth for the next life, but perhaps just as crucial a moment will occur while he remains in this one: his presence as a human being will be witnessed. For a population of people for whom the feeling of wind, or the taste of a cheeseburger, are distant memories, being witnessed is a profundity all its own.

The Independent and the nonprofit Responsible Business Initiative for Justice (RBIJ) have launched a joint campaign calling for an end to the death penalty in the US. The RBIJ has attracted more than 150 well-known signatories to their Business Leaders Declaration Against the Death Penalty - with The Independent as the latest on the list. We join high-profile executives like Ariana Huffington, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, and Virgin Group founder Sir Richard Branson as part of this initiative and are making a pledge to highlight the injustices of the death penalty in our coverage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks