America’s long, long history of dirty presidential campaigns

Analysis: Slips by Trump and Biden are providing ammunition for latest round of attacks, ads and smears. And this is nothing new, says

Joe Biden must be senile. Did you see that video? Couldn’t even remember the place or the date or the year he was talking about. Donald Trump, too. He kept inventing words and then seemed to freeze. And what about Nancy Pelosi? Sounded like she was drunk. Wish a family member would step in and have a word. Sad, really.

This, at least, is the impression that may have been formed by anyone who had spent much time on social media in recent months, as the 2020 election cycle gathers heat and intensity.

A succession of videos, some more crude and obviously fake than others, have done the rounds, bringing whispers and accusations into the mainstream, and further raising legitimate questions about America’s three most significant politicians, all in their seventies. How they perform over the next 14 months will greatly determine the course of the nation.

If this toxic campaign of attack ads appears shocking, what is even more staggering is that there is little new about it. Dirty politics has been a constant presence in presidential campaigns, and one that has frequently determined the course of an election.

At a time when political discourse and media coverage is dominated by the falsehoods and brash attacks repeatedly fired off by Trump, it may come as a surprise to recall that in 2000, supporters of George W Bush, now championed by some as a “respectable” example of a Republican president, spread false rumours that his primary opponent, John McCain, had fathered an “illegitimate” child with an African American woman.

The smears were all the more painful because they were given fuel by the fact McCain and his wife, Cindy, had adopted a little girl, Bridget, from Bangladesh. A phone poll, seemingly designed to spread the rumour rather than obtain actual opinions, asked voters: “Would you be more or less likely to vote for John McCain, if you knew he had fathered an illegitimate black child?”

McCain, whose “Maverick” campaign had come to South Carolina having just won a surprise primary victory in New Hampshire, said it amounted to libel. “There wasn’t a damn thing I could do about the subterranean assaults on my reputation except to act in a way that contradicted their libel,” he wrote in his memoir Worth the Fighting For: The Education of an American Maverick. The Bush campaign denied any involvement, but he won South Carolina, captured the Republican nomination, defeated Democrat Al Gore by the narrowest of margins – 537 votes in Florida – and entered the White House.

The standard operating procedure of a campaign is to start positively, but also to go negative when they believe it will not boomerang backwards

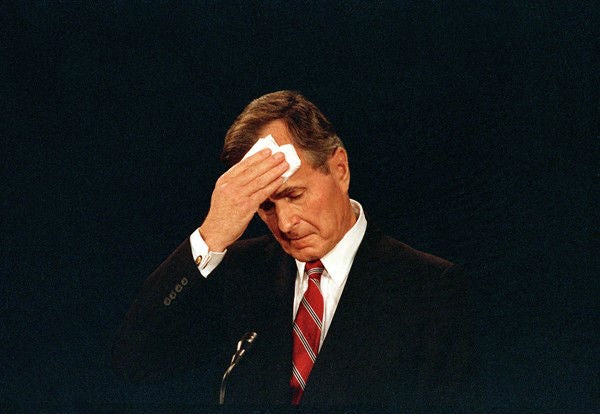

Bush’s father also had a hand in dirty politics. In his 1988 contest against Michael Dukakis, the Bush campaign used the now notorious Willie Horton advert to link the Democrat to an African American prisoner let out under a furlough programme in Massachusetts, where Dukakis was governor, and who then killed a woman. Dukakis had been leading in the polls, but the racially charged campaign badly damaged him, and Republicans were able to pull off the rare feat of holding the presidency for three for successive terms.

This sort of thing has been going on since America’s very first elections. Historian Rick Shenkman, author of Presidential Ambition: Gaining Power at Any Cost, has detailed how dirty tricks date back to the beginning of the republic.

“Our first two elections were pretty clean, but after that they became dirty,” he tells The Independent. “Even [America’s first president] George Washington complained he had to endure more attacks than Emperor Nero did.”

At a time, when the media was even more partisan than it was now, the nation’s third president, Thomas Jefferson, fought off accusations he had fathered children with one of his slaves. Jefferson was able to defeat incumbent John Adams, and 200 years later, his long relationship with Sally Hemings, a member of the staff at his Monticello plantation, was finally acknowledged by historians. The couple had six children.

Experts say the practice of dirty politics has continued, all the way down through Nixon 1972’s campaign against George McGovern and into our era, because it frequently works.

“They have very often been effective,” says Elaine Kamarck, director of the centre for effective public management at the Brookings Institution and a scholar at Harvard University. “The standard operating procedure of a campaign is to start positively, but also to go negative when they believe it will not boomerang backwards.”

Kamarck says the internet has increased the amount of messaging and disinformation that can be spread, and the way it can be targeted at certain groups. And while a 2002 “Stand by your Ad” law, also known as the McCain-Feingold Act, requires any adverts from a campaign or party on television or radio to be identified as such, usually by the candidate saying “I approve this message”, there is no such demand for the online world, which has emerged as an increasingly important battleground.

This means voters have less information as to whether an advert claiming a certain candidate hates Muslims is an official message, the work of one of the many massively funded political action committees (PACs), or disinformation spread by Russia.

At the same time, social media giants are struggling to determine how best to monitor and regulate such content. The most notorious of the doctored videos of Pelosi was taken down by YouTube, which said it violated its standards, but continued to be hosted by Twitter and Facebook, even though the latter tech firm deemed it false. In the end, millions watched the Democratic speaker of the House of Representatives apparently slurring her words in a speech.

Caroline Orr, a behavioural scientist at Virginia Commonwealth University, says negative campaigning and dirty tricks play to the emotions.

“It’s intended to arouse emotions so people don’t evaluate the information as critically as they might, and just internalise it,” she says.

“It’s successful a lot of the time because it feeds into people’s pre-existing beliefs. If somebody is sceptical about immigration and they see an inflammatory ad on that subject, they are more likely to believe it without measuring it. Time and time again, emotional appeal has proven to be the most effective.”

It’s pretty hard to shock people these days, whether it is politics or anything else. You’ve got to come up with something really good to make it stick

She said as more people relied on social media for their news, they became increasingly isolated from other view points “because the algorithms learn what you want to read”.

One of the many ways Trump has broken conventions as president is to spearhead attack adverts himself. Several times, Trump, 73, has claimed that 76-year-old Biden has lost it.

“Look, Joe is not playing with a full deck,” Trump told reporters this summer, after the former vice president made one of a succession of gaffes while campaigning, telling a crowd “poor kids are just as bright, just as talented, as white kids”.

Trump, along with his lawyer and surrogate Rudy Giuliani, also retweeted one of the several doctored clips of Pelosi, and the president annotated his post with the words “PELOSI STAMMERS THROUGH NEWS CONFERENCE”.

Even though there is large eco-system on the left that creates attack adverts about Trump, even if it is not as big as the one on the right, Biden has yet to resort to personal insults towards the president.

He and his campaign insist he remains as sharp as he ever was, despite doubts about his age among some supporters. He remains the Democrats’ frontrunner by some measure, leading his rivals by between four to eight points depending on which poll you examine.

David Mark, a senior journalist with the Washington Examiner and author of Going Dirty: The Art of Negative Campaigning, says another thing Trump has done is to raise the bar of what is shocking.

Among the early advisers to the Trump campaign was veteran operative Roger Stone who has long relished his reputation as a “political ratf***er”. In January, Stone pleaded not guilty to charges of witness tampering brought by Robert Mueller as part of his probe into Russia’s alleged interference in the 2016 election and possible collusion with the Trump campaign.

“Oh absolutely, it’s going to get more intense,” says Mark, looking to the coming months. If Biden becomes the Democrats’ nominee, he says, we should expect plenty of attacks about his hair, given that he appears to have more now than he did in the 1980s when he was a nearly-bald senator.

“Even though it’s going to be nastier than ever, I am not sure it’s going to have as as much impact because people are used to this stuff,” he says.

“It’s pretty hard to shock people these days, whether it is politics or anything else. You’ve got to come up with something really good to make it stick, and that is becoming increasingly difficult.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments