Yale scientists invent wearable Covid detector that can tell you how infectious your workplace is

The Fresh Air Clip can be pinned on a lapel or collar and requires no power source to pick up traces of coronavirus in the air around you

Keys and wallet? Check. Face mask and hand sanitiser? Check. Wearable Covid monitor? Not yet – but maybe soon.

The coronavirus pandemic has only increased the list of essential items we mustn't forget whenever we leave the house. Now scientists hope to add a tiny clip-on device that detects coronavirus in the air around its wearer.

A team of researchers at the Yale School of Public Health in Connecticut, US have developed a lightweight virus detector called the Fresh Air Clip that requires no power source and is easy to 3D print.

Originally invented to study other airborne substances such as pollutants and pesticides, the device could allow employers to cheaply track Covid exposure in high-risk workplaces such as hospitals and restaurants and give individuals one more tool to manage their own risk.

Yet it also faces a barrier to widespread adoption in the form of PCR tests, which are necessary to analyse each sample but sorely oversubscribed in the US, the UK, and elsewhere.

"This is really a complementary tool to all the other infectious control measures that are available," the team's leader Krystal Pollitt told The Independent. "We know that masking is an incredibly effective means for protection; we know that decreased occupancy and ventilation is effective.

"This is just another tool that can be used to alert people of potential exposure, and to highlight spaces that need more of these other controls to make sure that exposure is minimised."

She continues: "It's traditionally been very hard to measure airborne exposures, because of all the sampling equipment that's needed – it's typically very noisy, [with] pumps and cords.

"This type of style of monitoring lets you go into a space and take snapshots of what airborne levels are."

Each clip costs only $5-10 to make

The basic version of the Fresh Air Clip was already being worn across the world before the pandemic. Prof Pollitt's team had distributed it as a clip-on or a wristband for studies of environmental pollution, including to children with asthma.

The team were looking at various gases, pesticides and particles thought to contribute to disease, such as those given off by fossil fuels, cooking stoves, and home furnishings, in the hope of understanding the causes of conditions such as asthma and Crohn's disease.

“As soon as Covid started we appreciated the potential for it to be airborne,” says Prof Pollitt. “That's when we realised we should be using this device to also sample airbone virus.”

Over the next two years, Prof Pollitt's colleague Dr Dong Gao tested the clips in a rotating drum full of particles of a virus with similar properties to SARS-Cov-2, which causes Covid-19, designed to simulate the way airborne viruses move through spaces.

The team then distributed the clips to 62 volunteers who wore them to five days each. Five of the clips later showed traces of SARS-Cov-2; four of them were worn by restaurant staff, while the other's wearer worked at a homeless shelter.

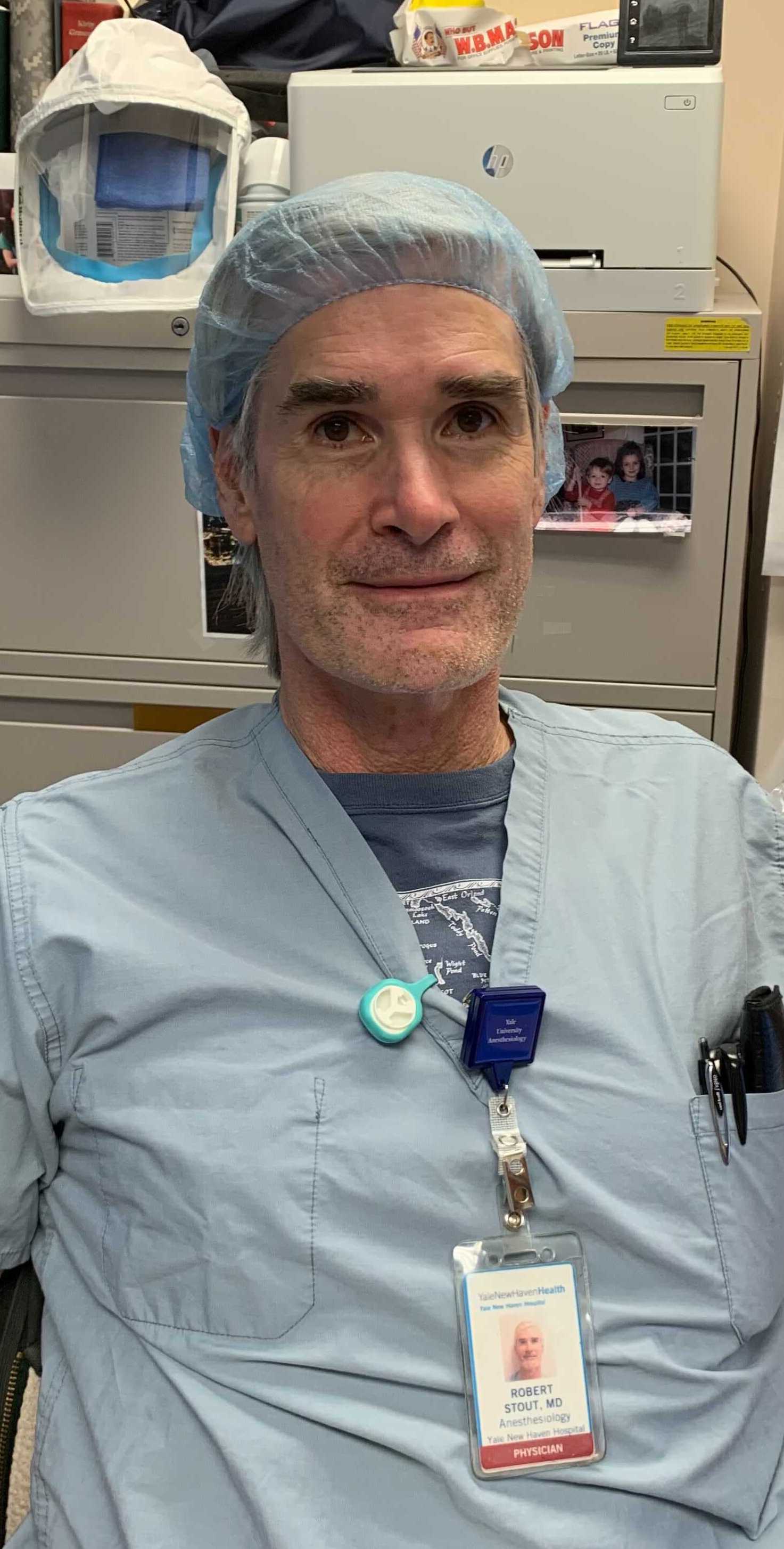

The clips themselves are simple, consisting of a plastic housing with a magnetic fastener so that it can be attached to a lapel or pocket. Inside is a slip of film made of a substance called polydimethylsilixane, or PDMS, which catches the particles.

Each device was then returned to a lab where its film was analysed via a PCR test – far more sensitive than the antigen or lateral flow tests used in home testing kits and capable of detecting the small amounts of virus that might be picked up through passing exposure.

Darryl Angel, a PhD student who conducted the testing, says the clips are a world away from “active” air samplers that require a power source and are rarely portable. She estimates the cost of each test at $14 (£10.38), with the device itself costing only about $5 to $10.

And, since the clips don't test any bodily samples or fluids, they don't require clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), meaning it would not be difficult to begin mass production.

'Testing is the major challenge'

The big bottleneck for the Fresh Air Clip is testing. While Ms Angel is testing ways to streamline the process, those methods require sophisticated automation equipment that is not yet widely available.

In the meantime, both the US and the UK suffered from severe testing shortages over the Christmas holidays, with the British Government's central testing website at one point showing no PCR tests available anywhere in England.

The clips are also unlikely to be much help tracking individual exposures, compared to a close contact with someone known to be infected even a notification from a contact tracing app.

If you wear a Fresh Air clip for five days and then get a positive result, you won't know where and when it picked up the virus. Nor are you likely to know how close or long-lasting the exposure was. The Yale team are still researching ways to assess whether an individual clip has registered the amount of virus necessary to infect someone.

Still, Prof Pollitt says it could help individuals assess how much risk they are taking on in certain spaces. "It's giving people the choice to be able to understand what they're exposed to, especially if they do feel like they they are in high risk environments," she says.

The biggest benefit is likely to be to institutions, which could issue the badges to staff or customers to get a systematic picture of how much they are being exposed to the virus on a daily basis.

Higher than expected results might indicate that more ventilation equipment or new safety rules are necessary, or even that existing ones are not working and need to be beefed up.

For now Prof Pollitt's team are trying to figure out how to deploy the devices on a larger scale, as well as use them to test for a wider range of viruses. It is already being tested by health care providers at various facilities in Connecticut.

“It's not decades away,” says Prof Pollitt. “It comes down to being able to do the analysis in a timely manner. Before we start offering that service, this is the challenge that we have to overcome.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks