Mark Zuckerberg's Facebook censors images of the Prophet Mohamed in Turkey – two weeks after he declared 'Je Suis Charlie'

Facebook CEO said: 'We never let one country or group of people dictate what people can share across the world'

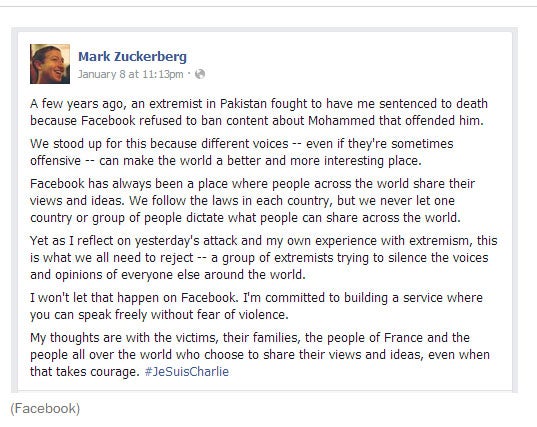

Only two weeks after Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg released a strongly worded #JeSuisCharlie statement on the importance of free speech, Facebook has agreed to censor images of the Prophet Mohamed in Turkey — including the very type of image that precipitated the Charlie Hebdo attack.

It’s an illustration, perhaps, of how extremely complicated and nuanced issues of online speech really are. It’s also conclusive proof of what many tech critics said of Zuckerberg’s free-speech declaration at the time: Sweeping promises are all well and good, but Facebook’s record doesn’t entirely back it up.

Just this December, Facebook agreed to censor the page of Russia’s leading Putin critic, Alexei Navalny, at the request of Russian Internet regulators. (It is a sign, the Post’s Michael Birnbaum wrote from Moscow, of “new limits on Facebook’s ability to serve as a platform for political opposition movements.”) Critics have previously accused the site of taking down pages tied to dissidents in Syria and China; the International Campaign for Tibet is currently circulating a petition against alleged Facebook censorship, which has been signed more than 20,000 times.

While Facebook doesn’t technically operate in China, it has made several recent overtures to Chinese politicians and Internet regulators — overtures that signal, if tacitly, an interest in bringing a (highly censored) Facebook to China’s 648 million Internet-users.

Now, the BBC has reported, Facebook has blocked an unspecified number of pages that “offended the Prophet Mohamed” after receiving a court order from a local court in Ankara. A person familiar with the matter but not authorized to speak publicly confirmed to the Washington Post that Facebook had acted to “block content so that it’s no longer visible in Turkey following a valid legal request.” In the past, social media companies that failed to comply with such requests — including Twitter and YouTube — have been blocked in the country, entirely.

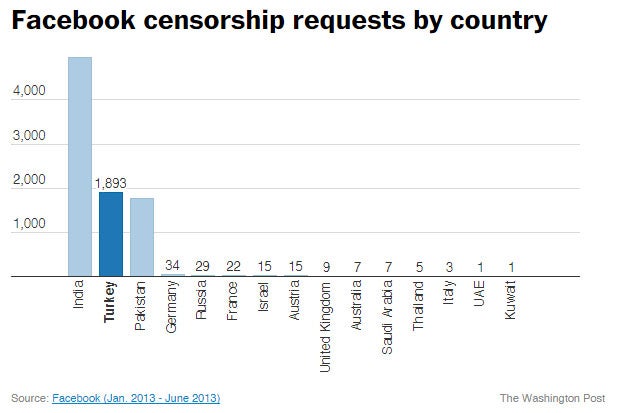

Turkey is, in fact, one of Facebook’s more vexing territories, at least where censorship is concerned. The country represents a huge potential audience for U.S. tech companies, with its growing population of young digital natives and its rapidly transforming economy.

But according to Facebook’s latest transparency report, which covered the first six months of 2014, Turkey asked Facebook to censor 1,893 pieces of content in that timespan — the second-most of any country. Many of the requests sprang from local laws that prohibit criticism of Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, or the president or the Turkish state. (Turkey takes this stuff seriously, too: You may have heard about the teenager who was arrested in December simply for reading a statement that criticized President Tayyip Erdogan.)

Facebook is a global company, of course, and must obey the laws of each country it operates in; the site can’t exactly pick and choose which regulations it finds agreeable, and it’s the site’s long-standing policy to comply with subpoenas, warrants and other government requests, provided they meet what Facebook calls a “very high legal bar.” (The company declined to comment on this particular case.)

Still, there’s something a bit grating about the decision, coming so very soon after Zuckerberg’s rosy-eyed epistle on free speech. It would be unfair to fault Facebook for complying with a legitimate foreign government request, regardless of how repressive it may seem. But for Facebook to do that while simultaneously styling itself as the patron saint of political speech? It seems a little disingenuous, to say the least.

“I’m committed to building a service where you can speak freely without fear of violence,” Zuckerberg said in his Hebdo statement.

He forgot that little asterisk: “… as long as what you say follows the censorship laws in your country, and as long as said country doesn’t ask us to take it down.”

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments