Rohingya refugees 'terrified' at prospect of being forced to return to Myanmar

‘If they forcefully deport us, we will be in the same situation that was there before. The violence, the killing, and the persecution [will start] again’

Plans to begin the repatriation of Rohingya Muslims from Bangladesh back to Myanmar next week are premature and have left the community in the world’s largest refugee camp “terrified”, according to aid groups.

Despite previous commitments that the return of Rohingya refugees would be on a safe, dignified and voluntary basis, the governments of Myanmar and Bangladesh announced a deal to begin with more than 2,000 repatriations from the Cox’s Bazar camps on 15 November.

The UN has said conditions in Rakhine state, from which some 700,000 Rohingya fled in a mass exodus starting last year, “are not yet conducive for returns”.

And there are now serious concerns over how the list of initial returnees has been drawn up, with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees confirming that it has not been included in the process by the Bangladesh government.

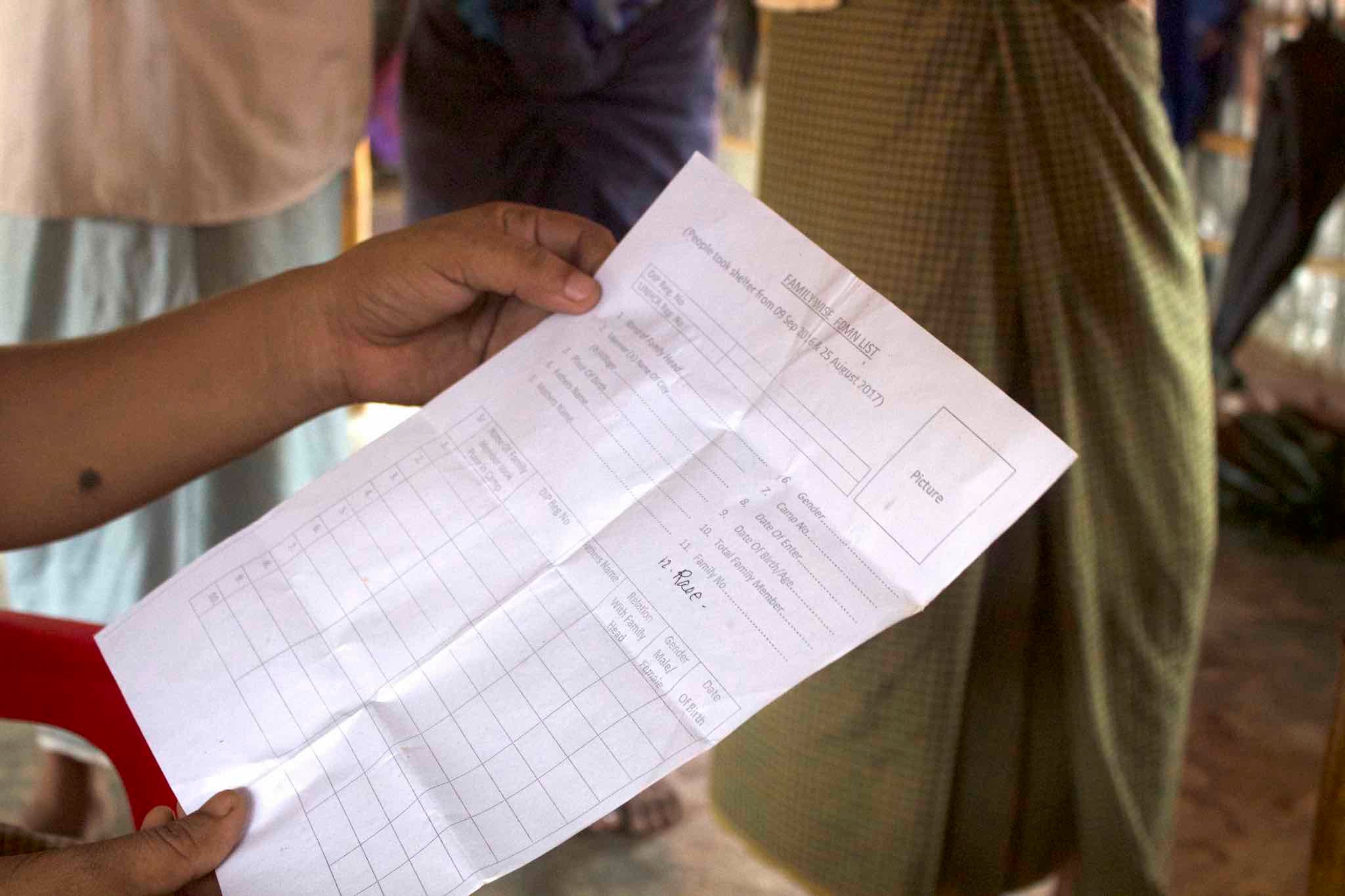

Official forms for counting Rohingya families have been given to refugees over the past few weeks. Refugees told The Independent that they feared the forms related to repatriation, but were ordered to fill them out anyway. No one The Independent spoke to was willing to volunteer to return to Myanmar under current conditions.

Now 42 international aid agencies have signed a joint letter urging Bangladesh and Myanmar to reconsider the repatriation plan.

It says the involuntary return of refugees would be a “violation of the fundamental principle of non-refoulement” – the internationally agreed principle that refugees cannot be returned to countries where they justifiably fear persecution.

“They are terrified about what will happen to them if they are returned to Myanmar now, and distressed by the lack of information they have received,” the letter reads.

Bangladesh has not released the list of names of the first 2,300 returnees, making it impossible to verify whether they are indeed being sent back on a voluntary basis.

The lack of official information has led to the widespread fear among many in the sprawling Cox’s Bazar camps that they could be “on the list”.

One 60-year-old man named Dil Mohammad tried to kill himself this week after the false rumour spread that he was being sent back, his wife told The Telegraph.

And multiple refugees told The Independent last month that if they were included on any list for repatriation to Myanmar, they would do all they could do avoid going.

Nurul Amin, a 37-year-old father of seven, said: “I saw the violence myself in Myanmar, I have seen people with their throats slit, and my house was partially destroyed by a grenade launcher [fired by the Myanmar army].

“We are thankful to this country’s people, the Bangladeshi people, to give us the shelter, we are grateful to them.

“But I am worried that they [the camp authorities] have taken all this information, that it might be a preparation for deportation.

“We are fearful of that if we are forced to go back there, then the violence and oppression will happen against us again.”

“We won’t go there,” said Muhammad Ali, 30. “We won’t go back. We will refuse to go.

“If they forcefully deport us, we will be in the same situation that was there before. The violence, the killing, and the persecution [will start] again.”

Sayeeda Kathoum, a 32-year-old mother, said “it makes [her] so happy” to see her daughters learning in the camp’s schools, and that back in Myanmar, Burmese teachers had refused to provide lessons to her children.

“We are worried, because many people are talking about deportations now, whether it is rumour or not. We are worried because we have seen the violence – that the men are killed, the women are abused and raped. We don’t want this to happen all over again,” she said.

The announcement of the start of repatriations appears to have coincided late this week with dozens of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar and Bangladesh boarding boats to try to reach Malaysia.

One boat was prevented from setting sail from the southern coast of Bangladesh on Wednesday, the coast guard said, while 33 Rohingya and six Bangladeshis were detained aboard a fishing boat bound for Malaysia, an official told Reuters.

A spokesperson for the UN refugee agency in Myanmar said the organisation had heard “similar reports” of boats leaving the country but could not confirm their location.

The spike in activity has raised fears of a repeat of the deadly situation in 2015, when a sudden government crackdown on Rohingya using boats to flee to Malaysia and Thailand left thousands abandoned at sea.

For years, people smugglers on both sides of the Bangladesh-Myanmar border have profited from the persecution of the Rohingya minority, most commonly in the dry months between November and March when the sea is calm.

But Chris Lewa, director of the Arakan Project, a monitoring group which has a network of sources across Rohingya communities, suggested the repatriation deal may have forced refugees into the hands of smugglers in greater numbers.

“The Rohingya are trapped,” she said. “They have nowhere to go. No one wants them, and now they face on top of that the threat of repatriation.”

Myanmar’s government denies allegations of crimes against humanity towards the Rohingya during its crackdown on militant activity in Rakhine in August 2017.

It says it wants the Rohingya to return, but only to internment camps like the one in central Rakhine that has housed some 120,000 Rohingya in cramped conditions, and with no freedom of movement or path to citizenship, for many years.

Yanghee Lee, the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, warned in a statement this week against “rushed” attempts to return the Rohingya, saying they still face “a high risk of persecution”.

Ms Lee said she had not seen any evidence of the government of Myanmar creating an environment where the Rohingya can return to their place of origin and live in safety with their rights guaranteed.

Myanmar has “failed to provide guarantees they would not suffer the same persecution and horrific violence all over again”, Ms Lee said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments