The saffron censorship that governs India: Why national pride and religious sentiment trump freedom of expression

When India banned a BBC documentary about rape, it was motivated by more than misplaced national pride. Like other examples of state censorship that bode ill for the supposedly secular democracy, this was a sop to hardline Hindu factions, says Zareer Masani

It sounds like an oxymoron: the world's "largest democracy" routinely curtails freedom of expression. But it's the truth. Earlier this month, the Indian government's ban on Leslee Udwin's India's Daughter, a BBC documentary about rape – combined with a demand that it also be banned in the wider world – focused international attention not only on the country's appalling record of violence against women, but on its sweeping censorship laws. The film was suppressed under an old colonial catch-all provision for threats to public order and decency. All that was required was for the Delhi police to tell a magistrates' court that the film "may lead to widespread public outcry and serious law and order problems".

India has no blasphemy law; its constitution proclaims the country a secular republic with freedom of expression as a fundamental right. But the constitution also prohibits anything that might offend religious sensitivities. The result has been a minefield for any Indian artist, author or performer who wants to push the boundaries, especially in areas of sexual or religious morality. (Foreign journalists face even more hyper-sensitive responses if they dare to offend national pride.) And every day it gets more dangerous, as attempts grow to draw together the diverse strands and sects of traditional Hinduism into an organised religion, with a centralised hierarchy of priests and a unified worldwide congregation, modelled in some respects on Christian churches.

India's draconian censorship laws date back to 1927, during the British Raj, when a book about the alleged sexual promiscuity of the prophet Mohamed provoked major riots by outraged Muslims in the Punjab. The Hindu publisher of the book was murdered by a Muslim assassin, who promptly became a hero of his community. Faced with serious Hindu-Muslim conflict, the British authorities, with the support of all Indian political parties, quickly enacted what became the bedrock of Indian censorship – Section 295 (A) of the Indian Penal Code. This states that anyone who outrages religious feelings or insults religious beliefs "with deliberate and malicious intention" may be imprisoned for up to three years, and it has been used extensively over the past 80 years to ban theatre performances and art exhibitions, to confiscate books and to bully authors and publishers into withdrawing their works.

The most celebrated case was the ban on Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses in 1988, under pressure from militants in India's 150 million-strong Muslim minority. But the Rushdie ban had important precedents. In the 1930s, the colonial authorities used their newly acquired censorship powers to pander to Hindu outrage by banning The Face of Mother India, an American feminist's diatribe against the sexual exploitation of Hindu women. The author, Katherine Mayo, had documented horrific case histories of child marriage and rape, including sexual injuries to young girls whom she had interviewed in Indian hospitals. (There are parallels here with British reporter Leslee Udwin's current portrayal of one of India's most horrific gang rapes.) But Mayo's findings were undermined by the racism of many of her beliefs, including her assumption that "Hinduism" glorified male lust.

While some Indian liberals and feminists opposed the ban on Mayo's book, nationalists were unanimous in their condemnation. Mahatma Gandhi famously likened her to a drain inspector – she had come to India in search of filth and dredged up whatever sewage she could find – and since then, national pride and religious sentiment have always trumped freedom of expression in defining the limits of state consent.

Growing up in the 1950s, in what was then called Bombay, I remember the excitement of reading a forbidden book my parents had smuggled in from a trip abroad – Rama Retold, a satirical retelling of the Hindu epic Ramayana. In this version, the legendary hero Rama – deified today, by Hindu revivalists – is depicted as a male chauvinist dolt whose wife Sita understandably succumbs to the charms of the very suave and scholarly Sri Lankan king Ravana (usually depicted as a demon and burnt in effigy by Hindus at the festival of Dussehra every year).

The author of this iconoclastic work was Aubrey Menen, who – being gay, anglicised and half-British – was therefore easily dismissed as a deracinated sexual pervert who had no business mocking Hindu orthodoxy. The government of the day was Jawaharlal Nehru's secular, socialist regime; even so, it crumbled in the face of Hindu anger. A shamefaced Nehru later apologised to Menen, admitting that it would have been politically too damaging to refuse a ban. But his daughter, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, had no such compunctions in 1970, when she expelled the BBC from India for two years after it ignored her government's ban on a film series by Louis Malle and broadcast the programmes in the UK. Like India's Daughter today, the Malle documentaries, which depicted terrible poverty and corruption in the sub-continent, were deemed "anti-Indian".

These are far from isolated examples. Though designed to protect religious sensitivities, Section 295 (A) has often been invoked to protect the reputation of secular heroes such as the 17th-century, Western-Indian Maratha king Shivaji, who fought alleged Muslim oppressors; his 20th-century successor, Bal Thackeray, who led Maratha regional chauvinism in Mumbai; and even Mahatma Gandhi, when an American biographer hinted at his latent homosexuality. And where Section 295 cannot be stretched to fit the offence, the Indian Penal Code obligingly offers the even wider remit of Section 153(A).

This edict proclaims: "Whoever (a) by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise, promotes or attempts to promote, on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any other ground whatsoever, disharmony or feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different religious, racial, language or regional groups or castes or communities, or (b) commits any act which is prejudicial to the maintenance of harmony between different religious, racial, language or regional groups or castes or communities, and which disturbs or is likely to disturb the public tranquility... shall be punished with imprisonment which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both."

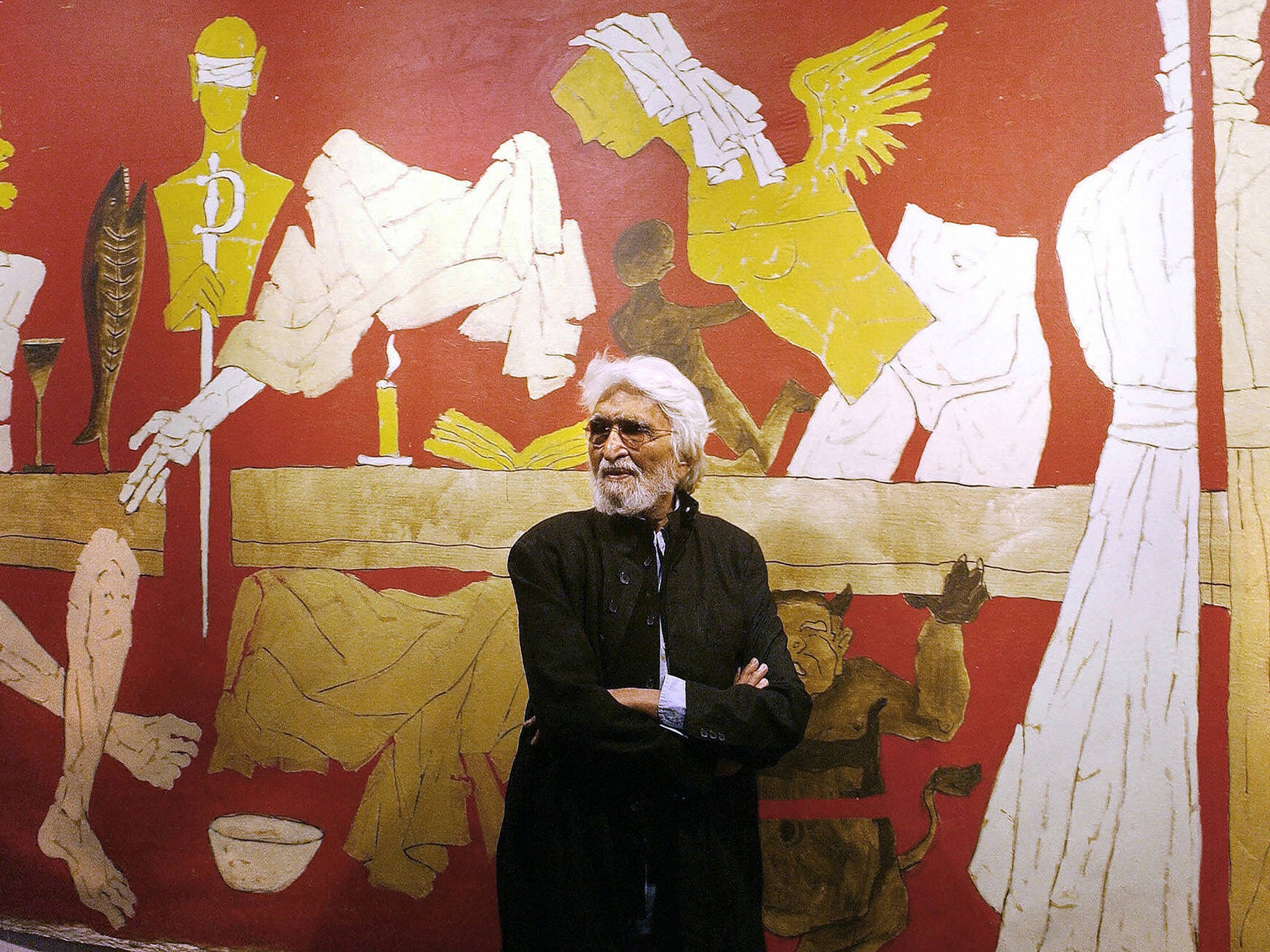

It's hard to imagine a wider censors' charter, and groups of all sorts have made the most of it. However flimsy the allegations, the notoriously slow and expensive workings of the Indian courts are usually enough to scare off authors and publishers, and the result has been a high degree of self-censorship. The danger of a hostile demonstration can also be used as a self-fulfilling threat to public order, and on that basis local police may refuse permission for a public event. Recent targets have ranged from visiting Pakistani cricket teams to a jazz ensemble with Pakistani musicians, both threatened by Hindu regional chauvinists of the Mumbai-based Shiv Sena party. But the most tragic victim of Indian religious intolerance was M F Husain, India's greatest modern painter, who was driven, in his nineties, to end his days in exile.

As an Indian Muslim, Husain epitomised the country's multicultural dream, with his hugely colourful, Picasso-esque paintings and murals, drawing liberally on Hindu mythology. But when Hindu extremist groups got wind of his paintings depicting Hindu goddesses nude, as they are in ancient temple sculptures, they filed a series of criminal prosecutions against him for profaning their faith. In 2006, faced with threats of physical violence, Husain left India, never to return. The chair of India's National Gallery of Modern Art, Pheroza Godrej, met him in Abu Dhabi some years later and begged him to return. "Can you guarantee the safety of my hands?" he asked her sadly, "Because if they break my hands, I am nothing." She had no reply.

Has such religious censorship grown tighter since last year's landslide election victory for Narendra Modi's BJP? The ruling party, whose initials stand for Bharatiya Janata (that is, "Indian People's") Party, claims to respect all religions, but its election machine relies heavily on paramilitary cadres of Hindu revivalist groups. These extremists expect their pound of flesh in return – and the ideas that they want to promote are every bit as worrying as their desire to ban alternative views.

One example is a campaign to rewrite school textbooks from a Hindu perspective, portraying the previous eight centuries of Muslim and British rule as an oppressive period of forced religious conversions and the destruction of India's authentic Hindu civilisation. But their born-again Hinduism, now called Hindutva, is very different from the tolerant polytheism of the past, which welcomed virtually any form of worship including Buddhism and Christianity.

"I would describe this new Hindutva as a kind of syndicated Hinduism," says Professor Romila Thapar, India's leading medieval historian. "It's borrowing from Western models to create an organised, ecclesiastically run religion which might be used politically in a fascistic way to deny India's traditional plurality."

Hindutva is also deeply puritanical. It has inspired the recriminalisation of homosexuality in India, and recently launched an assault on another Western study of Hinduism, that focused on its sexual tolerance and eroticism. In an ironical counterpoint to the banning of Mayo's The Face of Mother India, which condemned Hinduism for its sexual indulgences, Professor Wendy Doniger, of Chicago University, found herself under fire for taking the opposite view and celebrating Hindu sexuality. Her book, The Hindus: An Alternative History, was dragged through the courts by Hindu groups who eventually got her publisher to withdraw it last year.

"Some elderly Hindu gentlemen went to court and said I had offended them, which I clearly had," says Wendy Doniger with a laugh, pointing to the very loose wording of the dreaded Section 295 (A). I tracked down the leader of this league of Hindu gentlemen, a retired schoolteacher called Dinanath Batra, in a Delhi suburb. He was fanatical about his vision of an idealised Hindu past which led the world in everything from nuclear science to plastic surgery. Professors Doniger and Thapar, he maintained, were "demeaning" Hinduism by suggesting that its epics were works of fiction, rather than historical fact.

Such obscurantist thinking, no longer confined to a few elderly Hindu gentlemen, finds expression in the speeches of Narendra Modi himself, even while he strives to appear as a modernising, business-friendly, 21st-century Prime Minister. Opening a new hospital, he asserted in all seriousness that the elephant-headed god Ganesh was an example of ancient Indian skill at plastic surgery, and that the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, contains evidence of stem-cell research and IVF pregnancies. A BJP supporter recently regaled the Indian Science Congress with equally absurd claims that Rama flying about on a divine eagle in the Ramayana was evidence of ancient Hindus using sophisticated spacecraft.

Fantasies like these may sound harmless enough, but they coincide with the growing spate of violence against Hindutva's perceived enemies. India's Christian minority is under attack. Homophobia and misogyny are on the rise. "The modern Indian woman is seen as Public Enemy No 1," says Sagarika Ghose, a well-known television presenter who was eased out of her job after a pro-BJP takeover at her station. "There's a sort of cultural anxiety caused by globalisation, and it's allied to right-wing politics. Anything Western is attacked. Women who wear jeans or even carry cell phones are being targeted on university campuses." The most horrific example of such misogyny was the gang rape and murder of the young Delhi career woman who was the subject of India's Daughter.

In an unusual show of unity, politicians of both the ruling and opposition parties joined together to condemn the film for denigrating India's image. But encouragingly, they were met by an equally vociferous chorus of protest against the ban from almost the entire Indian media, including the Editors' Guild, and from most anti-rape, human rights and women's organisations. (This represents a widening gulf over censorship between India's political class and its urban intellectual and cultural elite.) Meanwhile, a positive outcome of the ban was that it proved so counter-productive – driving thousands of Indians who might otherwise have ignored the film to watch it online or in improvised screenings.

Along with the continuing debate across the Indian and global media, might this persuade the censors of the futility of their actions in the age of social media and the internet? The truth is, India remains too complex, diverse and open a society to be confined within a narrow cultural straitjacket – and the paradoxes aren't just evident in Prime Minister Modi's split personality (the modern liberal economist who believes that Ganesh had a head-transplant). They are also apparent in his party – in the tension between its chauvinist religious revivalists and those who represent business interests and are keen to attract Western investment.

In the long run, though, money may speak louder than words. It's significant that Prime Minister Modi, unlike Mrs Gandhi in the 1970s, has taken no punitive action against the BBC for defying his government's ban.

Dr Zareer Masani is a historian and broadcaster. His documentary, 'Saffron Censorship: India's Culture Wars', is on BBC Radio 4 on Monday at 4 pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks