Adolf Hitler really is dead: scientific study debunks conspiracy theories that he escaped to South America

Fuhrer’s appalling oral hygiene allows jawbone held in Moscow to be identified by its false teeth. French study also challenges US claims that skull fragment was from a woman

A peer-reviewed study in an academic journal has proved what you might have assumed you already knew: Adolf Hitler is dead and has been since he killed himself in his bunker in April 1945.

That scientists are devoting serious attention to proving this more than 70 years after the event may initially seem bizarre.

But almost from the moment the Führer died, a cottage industry of conspiracy theories sprang up to say he was still alive.

Hitler has been “spotted” emerging from a German U-boat in Argentina with Eva Braun in 1945, surrounded by adoring fugitive Nazis in 1950s Columbia, and approaching the end of his days in the 1980s as a happy nonagenarian with a younger Brazilian girlfriend.

Now, though, French scientists have been allowed to examine a jawbone that has been jealously guarded in the archives of the Russian secret service since the 1940s.

The analysis published in the peer-reviewed European Journal of Internal Medicine suggests that in this instance the Russians were telling the truth: Hitler killed himself, SS soldiers burnt his body, Soviet troops found the charred remains, and the jawbone ended up in Moscow.

The snappily entitled study – The remains of Adolf Hitler: A biomedical analysis and definitive identification – recounts how the French researchers were allowed access to the jawbone in the archives of Russia’s FSB – the successor to the KGB – in March and July 2017.

The lead author of the research, Professor Philippe Charlier, told a French documentary that it had been possible to compare the jawbone held by the Russians to Hitler’s dental records, thus allowing the Führer to be identified by his false teeth.

Prof Charlier said that despite being only 56 when he died, Hitler had just five of his own teeth left.

“We first identified him by his dentures, which were extremely unusual, in completely extraordinary shapes,” Prof Charlier told the documentary team. “There was a perfect anatomical and technological correspondence.”

The conclusion was further corroborated by electron microscope analysis of tiny samples from Hitler’s few remaining real teeth, which found no traces of meat – significant because despite his murderous intent towards humans, Hitler was a vegetarian.

The state of the dentures also seemed to tally with the traditionally accepted account that Hitler took cyanide before a bullet was fired into his skull.

The research team suggested that bluish deposits on the dentures might indicate a chemical reaction between the cyanide and the metal dentures.

The French researchers also went some way to contradicting a University of Connecticut study, which in 2009 caused a sensation by claiming that a skull fragment with a bullet hole – stored in a different location to the jawbone – was from a woman, not Hitler, and not Eva Braun, because she poisoned rather than shot herself.

The American academics had been able to examine and take DNA samples from the skull fragment that ended up in the Russian State Archive in Moscow.

They did not, however, examine the jawbone in the possession of the FSB.

For the French researchers the situation was almost reversed: they were allowed to take material from the jawbone, but were only able to look at the skull fragment without taking DNA samples from it.

This meant they were not able to fully replicate the American testing which found female DNA, but Prof Charlier insisted that anthropological examination of the skull fragment could not establish the dead person’s gender.

“From the anthropological perspective, that absolutely doesn’t hold,” he said. “When doing a diagnostic of the skull, you have a 55 per cent chance of getting the sex right. That’s not much better than chance.”

The University of Connecticut findings were used by a TV production team as the basis for a documentary that was broadcast on the History Channel with the sensational title Hitler’s Escape.

Suggesting such a conclusion from the skull fragment alone may have been risky, however.

The new French study seems to suggest that whatever the provenance of the skull fragment, the jawbone is from the Führer and therefore there was no miraculous escape for Hitler.

Moreover, the jawbone’s authenticity seems to be further corroborated by the publication last month of the English translation of the memoir of wartime Russian interpreter Elena Rzhevskaya.

Ms Rzhevskaya, who died last year but who published her account in Russian in 1965, told how in May 1945 she was part of a Smersh counterintelligence unit scouring the ruins of Berlin for Hitler’s body.

She described her commanding officer handing her a cheap jewellery box and telling her, when she asked what was inside: “Hitler’s teeth. And if you lose them, you’ll be answerable with your head.”

As she opened the box and stared in amazement at the partially flesh-covered remains, the colonel explained that he had no access to a safe, so he was entrusting the Führer’s teeth to her because “as a woman, you’re less likely than a man to get drunk and lose them”.

With two superior officers, she went looking for Hitler’s dentist, only to find he had fled to Bavaria. But they found the dentist’s assistant, Kathe Heusermann, and – once they had reassured her they had not come to rape her – she took them to the dentist’s surgery inside the ruins of the Reich Chancellery.

There, Ms Rzhevskaya recounted, they found Hitler’s dental records and teeth X-rays.

The following day, just to be sure, interrogators asked Frau Heusermann to describe Hitler’s teeth from memory.

Ms Rzhevskaya, who was translating, recalled that what the dentist’s assistant said matched what was on the X-rays. And then, when Ms Rzhevskaya opened the jewellery box, Frau Heusermann blurted out: “These are the teeth of Adolf Hitler.”

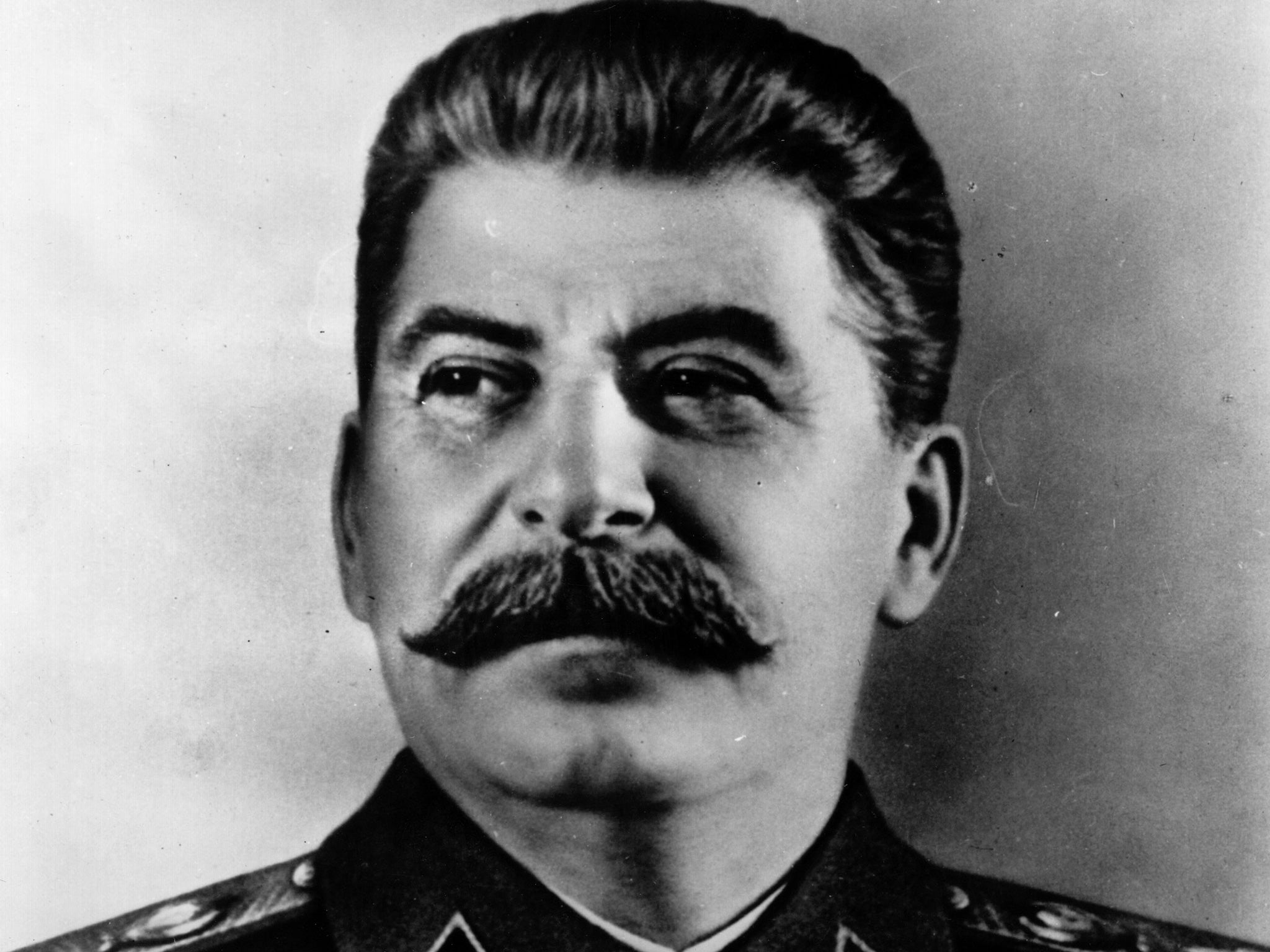

The blame for allowing this relatively straightforward identification of Hitler’s dead body to be obscured by tales of his continuing survival lies partly with his fellow dictator Joseph Stalin.

The historian Antony Beevor, author of Berlin: The Downfall, has written about how Stalin had been keen to reassure himself that Hitler was dead, but equally keen to hide this news from his supposed allies Britain and America.

Instead, the communist newspaper Pravda (Truth) said rumours that Hitler’s body had been found were a fascist provocation.

The Soviet authorities spread the “alternative fact” that Hitler was alive and well and being looked after by the treacherous Americans in their zone of occupation.

According to Beevor, writing in the New York Times in 2009, Stalin even went as far as misleading his commander-in-chief Marshal Georgi Zhukov by berating him over the supposed failure to find Hitler’s body.

This may help explain why, when a group of high-ranking RAF officers tried to visit Hitler’s bunker in 1946, they found it locked and guarded by an NCO from the NKVD secret police, who told the British delegation that Hitler had escaped and was now in hiding in Argentina.

The conspiracy theories had started, and over time they would multiply.

By 1955 the head of the American’s CIA base in Maracaibo, Venezuela, was writing a memo about a claim that Hitler was living in the Colombian Andes at the head of a community of fugitive German fascists who followed him “with stormtrooper adulation”.

But what actually happened to Hitler’s body seems to have been more mundane, though perhaps more comical.

After he and Eva Braun killed themselves on 30 April 1945, military aides carried their bodies out of the bunker into the garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they wrapped the Fuhrer’s body in a Nazi flag, doused it in petrol and set it alight.

They failed to completely burn the body, however, and ended up burying the charred remains in a shallow shell crater.

On the morning of 2 May, Soviet private Ivan Churakov spotted the freshly turned soil and started digging in the hope of finding hastily buried Nazi gold. Instead he found a leg bone.

Once Ms Rzhevskaya and her team had established who the remains belonged to, the all-important jawbone was sent to Moscow.

The Soviets buried the rest of the Führer on the outskirts of Berlin, moving the remains the following month to a forest near Rathenow.

Then in February 1946 they again disinterred the Führer and buried him in the grounds of the Russian army base in Magdeburg, in eastern Germany.

Meanwhile, in the same year, the ever-paranoid Stalin demanded extra reassurance that Hitler really was dead. So a second secret Soviet mission went to the shallow grave in the shellhole.

This mission recovered the skull fragment with the bullet hole, taking it back to Moscow where it ended up in the Russian State Archive.

Back in Germany the buried bits of Hitler lay undisturbed until March 1970.

But then the Russians decided to hand over the Magdeburg base to the East German government, presenting themselves with the problem of what to do with the body they had hidden beneath it.

The higher echelons of the Soviet leadership worried that if they didn’t take the body with them when they left the base, it might become a place of pilgrimage for neo-nazis.

Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB who would later become president, advised Russian leader Leonid Brezhnev that it would be “advisable to destroy the remains by incineration”.

This, it seems, was achieved by a trio of Russian soldiers being ordered to go on a bizarre “fishing trip”.

In 2001 Vladimir Gumenyuk, a then 64-year-old former Red Army soldier, told Russian media how on the night of 4 April 1970 he and two fellow soldiers were told to go and dig at a certain location.

Gumenyuk said they found some crates at a depth of 1.7m (5ft), loaded them onto a Jeep and at dawn drove off into the countryside, posing as off-duty soldiers with a set of fishing rods positioned to be immediately visible to any passer-by.

Then, beside a river, hidden by a screen of trees, the Russians allegedly poured petrol over the crates and burned Hitler’s body more thoroughly than his Nazi soldiers had been able to do in 1945.

Gumenyuk claimed he collected the ashes and scattered them from the top of a nearby hill.

“I opened up the rucksack, the wind caught the ashes up in a little brown cloud, and in a second they were gone,” he claimed.

He also swore to take the secret of where he had scattered the ashes to his grave.

Meanwhile, in 2000, the Russian State Archive displayed the skull fragment in an exhibition entitled The Agony of the Third Reich.

“It’s not just some bone we found in the street,” insisted archive boss Sergei Mironenko.

But if the intention had been to stop the conspiracy theories, the only result seems to have been renewed interest in the skull fragment, leading to the American claims nine years later.

Whether the French study has more luck in rebutting the conspiracy theories remains to be seen.

Given how the conspiracy theories about Hitler have survived for so long – even if the man himself hasn’t – it is anything but a foregone conclusion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks