European colonialists 'carried deadly dysentery bug with them to the tropics rather than bringing it back to Europe'

Study finds Europeans took dysentery microbe to their colonies where it became established as a deadly infection

European colonialists carried a deadly tummy bug with them to the tropics where it spread rapidly among the locals, rather than being infected overseas before coming back home with it, a scientific study into the origins of dysentery has found.

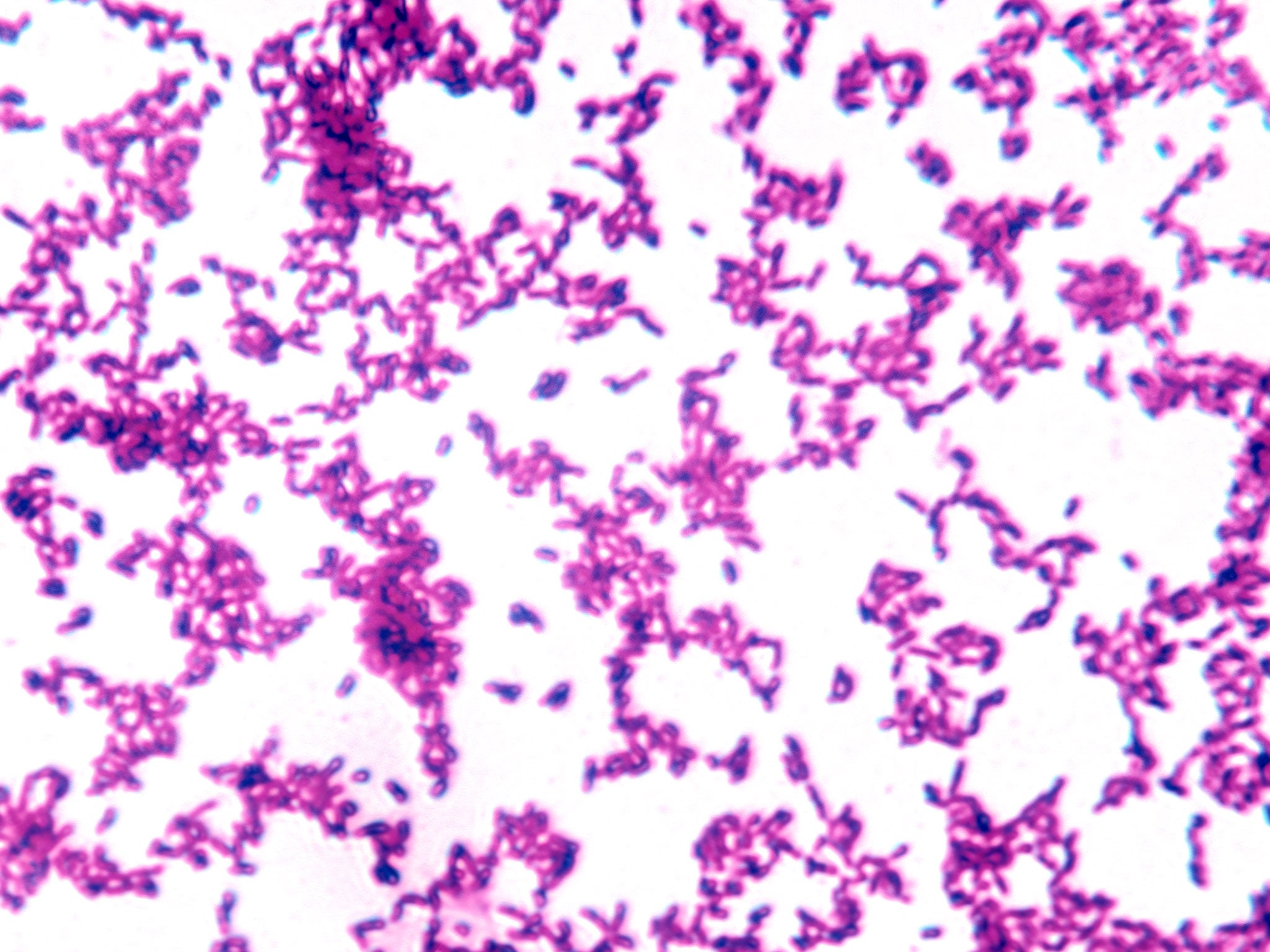

A genetic analysis of more than 300 strains of the Shigella bacterium, which causes life-threatening bloody diarrhoea, has found that it probably originated in Europe and was repeatedly carried to Asia, Africa and South America rather than the other way round, as some historians had previously suggested.

The study found that Europeans took the dysentery microbe with them to their colonies during the 19th and 20th Century where it became established as a deadly infection. Meanwhile, endemic dysentery in Europe quietly died out making it appear as if it was a gastro-intestinal disease had originated in the tropics.

The microbe, Shigella dysenteria, produces a powerful toxin known as Shiga, named after a Japanese doctor Kiyoshi Shiga who first identified it after an outbreak in Japan in 1897 which killed 20,000 people in six months. Large outbreaks have since occurred in the developing world, such as in Central America where half a million people were infected, killing 20,000, between 1969 and 1973. Tens of thousands more have since died of Shigella dysentery in Africa and South-East Asia.

Scientists from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge analysed the genomes of 330 strains of S. dysenteria isolated between 1915 and 2011 in 66 countries. They found that the main, type-1 strain has existed at least since the 18th Century and probably spread across the world from Europe, and has now become endemic in Africa and Asia.

Shigella dysentery, which thrives in unhygienic conditions with poor sanitation and water quality, famously first emerged among Europeans during the First World War when more than 120,000 casualties in the Gallipoli Peninsula had to be withdraw from the Dardanelles, most of whom were suffering from the disease.

The DNA from the type-1 strain that caused the 1915 outbreak, however, showed that it was much older, going back at least a century or two with an origin likely to be centred on Europe, the scientists found.

“Analysing the full genomes of all this Shigella dysenteriae strains collected over a huge timeframe and from such an array of different countries provided us with an unprecedented insight into the historical spread of this pathogen,” said Professor Nicholas Thomson of the Sanger Institute.

“This was needed because there are still many unanswered questions relating to this infamous and important bacterial pathogen. It was achieved by combining high resolution genome research data with the detailed information recording the provenance of each sample from a large number of dedicated groups,” Professor Thomson said.

By identifying the different genetic lineages of Shigella, the scientists were able to trace the movements of the bacterium across the world over time, clearly showing that European colonialism and migration helped to spread it among locals elsewhere in the world.

It appeared in America, Africa and Asia between 1889 and 1903, for instance, aided by the European emigration to America and the colonisation of territories in Africa and Asia. Although dysentery re-appeared in Europe during the First World War, is then died out, but it continued to cause violent outbreaks across Asia, Africa and Central America.

“This bacterium is still in circulation, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favourable, such as large gatherings of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste,” said Francoise-Xavier Weill of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, who led the study published in the journal Nature Microbiology.

“This study highlights the need for an effective vaccine, which will be crucial for controlling this disease in the future I view of the reduced efficacy of antibiotics,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments