European elections 2014: Marine Le Pen’s Front National victory in France is based on anguish, rage and denial

France’s lurch to the far right was more about finding scapegoats and yearning for the past, writes John Lichfield

If there was an epicentre to the “political earthquake” which struck France on Sunday, it was the tiny village of Brachay in the empty, eastern quarter of the country.

The village cast 28 votes, including 22 for the far right anti-EU Front National (FN). It also cast three votes for the far left, anti-EU Front de Gauche.

Not a single vote was cast in Brachay (population 59) for either of the “parties of government”: President François Hollande’s Socialists or ex-President Nicolas Sarkozy’s centre-right Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP).

Brachay is a quiet place in the Haute Marne in north-eastern France, with no crime, no immigrants, no unemployment to speak of and half a century of direct – or indirect – support from the EU farm budget. Why on earth should such a place reject the national establishment and vote mostly for two parties which want to destroy the EU?

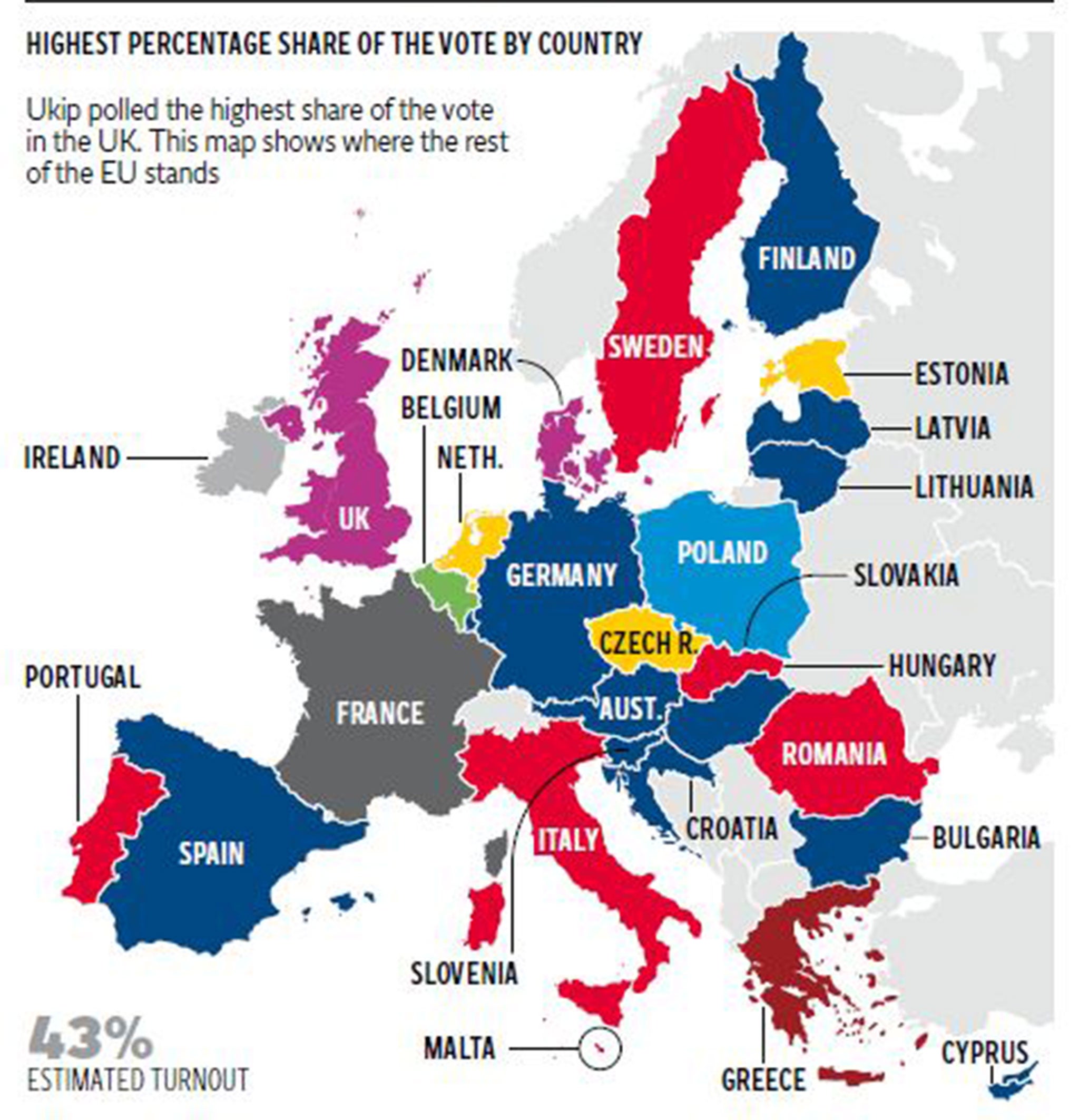

The same earthquake was felt right across France in Sunday’s elections. For the first time in French history a party of the far right, Marine le Pen’s FN, topped the poll in a nationwide election, with 25 per cent of the vote. Ms Le Pen will send 24 MEPs to Strasbourg – she will also go herself – an eight-fold gain on the last parliament.

President Hollande’s Socialists registered scarcely 14 per cent, their worst score in a nationwide election since the party was founded in the 1970s. The “main” opposition party, the UMP – heir to the Gaullists – scored only 20 per cent. This was a disastrous result for a party which expects to produce the next President of the Republic in 2017 (and probably will).

Several political health warnings need to be attached to the result. The turnout was only 43 per cent, compared to 70 per cent or more in national elections. Only one in four of those people who voted for Marine le Pen said that they thought that the FN’s policies – protectionism, scrapping the euro, halting immigration – would rescue the French way of life. Only one in five FN voters said that they opposed the EU.

Two-thirds of French voters have a visceral distaste for Ms Le Pen and the FN. She will play an important role in the next presidential elections. She might even, like her father in 2002, reach the second-round, two candidate run-off. She cannot be France’s first woman president.

Just a protest vote, then? No, far more than that: a vote of rage and a vote of anguish, but also a vote of denial. French voters insist at every election they want “change”. They don’t.

President Sarkozy was repudiated by the electorate after trying to make modest reforms to prepare France to compete in the 21st century. Two years later, his conqueror, Mr Hollande, is the least popular President in history after stumbling to the tax-raising left and then the tax-cutting right.

Neither left nor right has found a way to persuade the electorate to accept the sacrifices needed to rescue the French social and economic model in a threatening, globalised world.

Both left and right have offended by demanding sacrifice while indulging in selfish, or in some cases corrupt, behaviour. Most voters recognise that Marine le Pen offers no solution. She does offer a chance to express inchoate rage against politicians, against Europe, against immigrants, against the markets. She asks for no sacrifices. She offers scapegoats.

Brachay, like many similar villages, votes FN not because it is directly threatened by crime or by immigrants, but because it is scared by the world that it sees on the television. Equally, the wider French vote for the FN is an ostrich vote for the past; a vote against the present and a vote against an uncertain future.

Against this background, the similarities between the FN “victory” in France and the Ukip “victory” in Britain are striking – but misleading. In both cases, the party in power was pushed into third place. In both cases, the far right/populist vote was fuelled by a mixture of anti-Europeanism, anti-immigrationism and anti-“elitism”.

But Nigel Farage and Tory Eurosceptics believe that Britain would thrive in a globalised world without the alleged interference of the EU. Ms Le Pen is a protectionist who says that the EU is an Anglo-Saxon, market-fundamentalist conspiracy. She wants to build an economic Maginot Line around France.

The real danger of “Le Penism” is that it always reflects the French mainstream that it purports to reject.

The centre right UMP is already splitting between free marketeers and protectionists. Even the moderate French left is tempted by an anti-European statism and protectionism.

Similar tendencies are visible in Spain and Italy.

British Eurosceptics like to speak glibly of a post-EU continent as a “simple open market” in which the UK economy would thrive.

The high FN vote in France presages something else: a possible non-EU future of ruinous, beggar-my-neighbour devaluations, trade barriers and national antagonisms.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments