Germanwings crash Q&A: Is flying more dangerous?

The risk of harm from air travel remains extraordinarily low

One of the questions asked of the travel desk of The Independent after the loss of Germanwings flight 4U 9525 was: “Is flying getting more dangerous?”

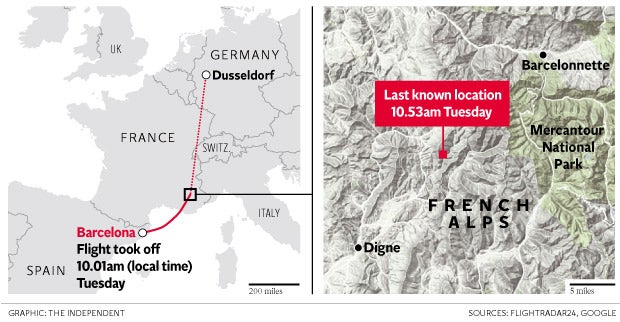

The crash in the French Alps is a tragedy, bring profound grief to the families, friends and colleagues of the victims. But it is also extremely rare - almost unimaginable - that a large European passenger jet, at cruising level on a routine flight across the safest skies in the world, should crash.

The question that investigators from Airbus in Toulouse and Germanwings’ parent airline, Lufthansa, urgently need to answer is: how did a tragedy like this happen in the 21st century? Meanwhile, airline passengers have their own questions.

Germanwings is a no-frills operator. Are low-cost airlines less safe than “full-service” carriers?

No. European airlines - both traditional carriers such as Lufthansa, Air France or British Airways, and no-frills operators such as easyJet or Ryanair - never skimp on safety. Rigorous safety standards are imposed equally across all airlines. Germanwings has exactly the same high standards as its parent, Lufthansa, whose safety record is formidable.

Lufthansa is Europe’s biggest airline. The last incident it suffered was on the runway at Warsaw airport in 1993, in which a crew member and a passenger died. Among the other very large European airlines, only British Airways, easyJet and Ryanair have better safety records than the German carrier. The last two have never suffered a fatal crash, while the last BA accident, at Manchester airport, was in 1986.

The aircraft was one of the oldest A320s still flying. Is that relevant?

No. A 24-year-old aircraft, as the doomed jet was, should not be regarded in the same way as a 24-year-old car might be. Every passenger plane goes through rigorous, regular checks. Everything, from the fabric of the aircraft to the avionics that control its flight, is kept in prime condition. No-frills airlines tend to have younger fleets than “legacy carriers”, but a well-maintained old plane is just as good and safe as a new one.

This is the second Airbus A320 crash in three months. Is the aircraft somehow “jinxed”?

Absolutely not. Since the A320 entered service in 1988, this aircraft has flown 80 million flights, carrying one billion passengers. The type has suffered 11 fatal accidents. That is an average of one calamity every two-and-a-half years. Six have happened in the past nine years, a rate of one every one-and-a-half years, but statistically that is to be expected because so many more of the jets are flying.

Could the two latest A320 crashes have a similar cause?

Unlikely. The circumstances of the loss of the AirAsia jet flying between Surabaya and Singapore in December have not yet been fully understood. But the most plausible current scenario involves an inappropriate reaction by the pilots to challenging weather in the shape of a fierce tropical storm. Today’s crash took place in calm weather.

Is Airbus more dangerous than Boeing?

No. Thankfully, crashes of passengers jets are so rare that meaningful statistical analysis is difficult. But looking at the computations of the leading aviation safety expert, Dr Todd Curtis of AirSafe.com, the two big airline manufacturers have broadly similar accident rates for their respective short-haul workhorses: the Airbus A320 and the Boeing 737.

The “full loss equivalent” rate of the A320 (and its sister aircraft, the A318, A319 and A321) is 7.65. The fair comparison to make is with later models of the Boeing 737, starting with the -300 series which launched in the mid-1980s; the earlier versions had much higher accident rates, a reflection of the much greater danger of passenger aviation at that time. The accident rates relative to the number of planes flying are very similar for both manufacturers.

Would “data streaming” have helped avert disaster - or enable us to understand what went wrong?

Not in this case. The purpose of data streaming, which has been much discussed since the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines MH370 last year, is not to alert people on the ground to possible problems. It is duplicate the information collected on board by the flight data recorders: conversations in the cockpit, and details of the pilots’ commands and aircraft performance. Because the crash location is known, recovery of the on-board flight data recorders was straightforward.

Is flying getting more dangerous?

No. In fact, of all the accomplishments of 21st century life, perhaps the greatest is the extraordinarily safety record of aviation. This year around 3.5 billion passenger journeys will be made. If the death rate of the previous years continues in 2015, about 1,000 people will die - most of them, sadly, on airlines in the developing world where safety standards are less rigorous.

In 2015 it is likely that 1.2 million people will die on the roads worldwide. And the number of victims in this plane crash corresponds to the average death toll in three weeks in crashes on German roads.

The risk of harm from air travel remains extraordinarily low.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks