Göring's brother was another Schindler

A German book reveals how Albert Göring saved the lives of dozens of Jews

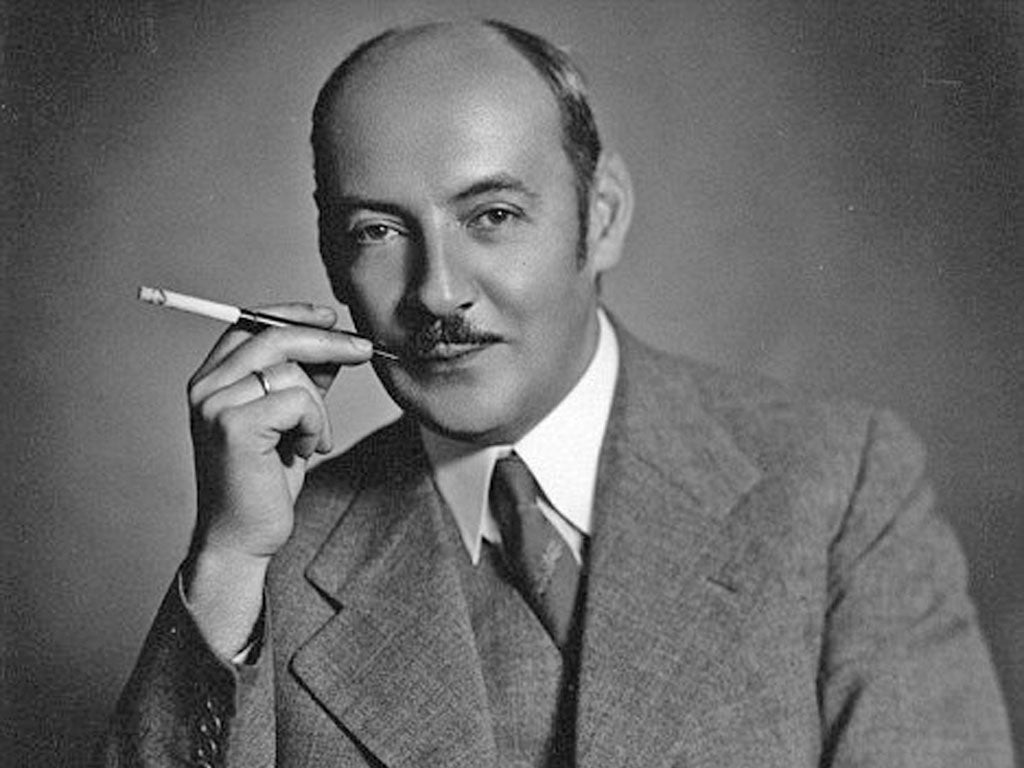

The stormtroopers had hung a placard around the neck of the terrified Jewish woman that proclaimed: "I am a Jewish sow". The mob standing near by on the streets of Nazi-annexed Vienna laughed and cheered with glee. But somehow a tall man with a moustache and receding hairline managed to push his way to the front and save her.

The woman escaped as her rescuer exchanged blows with two stormtroopers. The intruder was arrested but, after revealing his identity, he was soon free. The rescuer was Albert Göring, younger brother of Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, one of Hitler's closest associates.

Albert Göring saved the lives of dozens of Jews, yet in Germany his remarkable exploits have remained virtually unknown. Almost 70 years after the defeat of Nazism, a German-language version of his story has been published for the first time in Germany, where it has left book reviewers and readers astounded. "Is it really possible that Hermann Göring's brother was a resistance fighter who saved Jews, helped the persecuted with money and faked passports, even managing to secure the release of concentration camp prisoners?" asked Der Spiegel.

Hermanns Bruder: Wer War Albert Göring? is a German version of the Albert Göring biography, Thirty-Four, originally written in English by the Australian author William Hastings Burke, who named his book after the number of Jews Albert saved from death. "One of the reasons Albert's story has never been told before in Germany is because he himself refused to let anyone publish it," said the author. "Albert had friends in the film business who begged him to let them tell his story, but he was too modest to let them," he added.

Albert could hardly have been more different from his elder brother. He was brown-eyed, tall, slim, modest, loved music, and was married four times. Hermann was blue-eyed, fat, bombastic, militaristic, addicted to morphine, and a rabid anti-Semite. There was speculation that Albert was the result of a long-standing extra-marital affair his mother had with his godfather, a half-Jewish society physician called Hermann von Epenstein.

The Nazis were anathema to Albert. He refused to join the party and stole away to Vienna where he took Austrian citizenship and worked as a heating boiler salesman. But the Nazis caught up with him when they annexed Austria in 1938. Albert was evidently disgusted by their persecution of Vienna's Jews. He is reported to have knelt down and joined a group of Jews forced by stormtroopers to scrub pavements. Discovering who he was, the stormtroopers cleared off quickly.

With the help of his surname, Albert was able to save Jews from certain death in the gas chambers. He provided them with money and false papers to help them escape abroad, rather than be deported. He secured an influential job as the head of exports at the Skoda vehicle and weapons factory in Brno in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia. In 1944, he pulled off his biggest coup by freeing Jews from the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Having driven up to the camp in a lorry, he said, "I am Albert Göring from the Skoda works and I need workers," recalled Jacques Benbassat, the son of one of Albert's closest friends. "He filled his lorry with workers. The commandant gave the go-ahead because he was Albert Göring. But Albert just drove into the woods and set them free."

Albert had contacts with members of the Czech resistance who, after the war, testified that he had used knowledge gleaned from his brother to tell them of a secret U-boat shipyard and Nazi plans to invade the Soviet Union. The information was passed to Moscow and London.

By 1944, the Gestapo had got wind of Albert's activities. They issued a death warrant. Hermann intervened again, and asked Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo, to smooth the matter over, but he warned his brother that he could help him no more. The last time the two met was in a US army prisoner of war camp in the Bavarian town of Augsburg in May 1945. Hermann is reported to have told Albert: "You will soon be free: look after my wife and child." Hermann avoided the death sentence by committing suicide.

Albert was not released until March 1947. Former employees at Skoda testified in his favour. Yet life in postwar Germany was a disaster. The surname that had helped him save so many became a liability. Albert, a qualified engineer, was unable to find a job. He died poor, embittered and unrecognised in 1966.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks