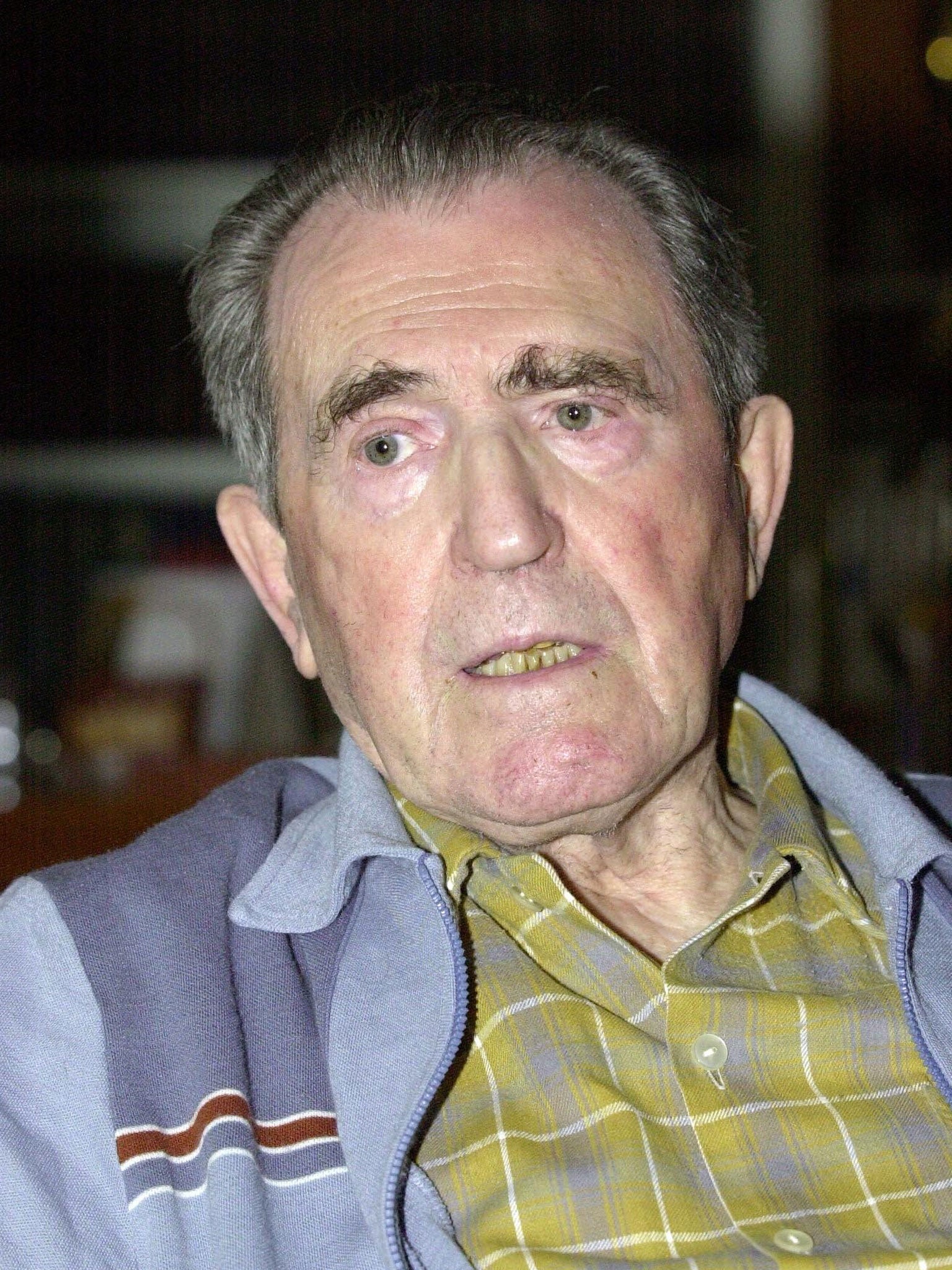

Hard-line Czech communist Vasil Bilak dies: Last surviving ‘tankie’ who supported 1968 invasion of his own country by Soviet Union passes away at 96

The invasion by massed troops of the Warsaw Pact was an event that shocked the world

He was the last surviving “tankie” – one of five hard-line Czechoslovak communists who in 1968 invited the Soviet Union to crush the passionate hopes aroused by the Prague Spring and invade their own increasingly reform-minded country with nearly half a million Warsaw Pact troops and some 2,000 tanks.

But today members of the Czech Republic’s now reformed Communist Party shed few tears at the news that Vasil Bilak, the veteran and staunchly pro-Kremlin former party member, had died at his home in the Slovak capital Bratislava after a long illness.

Announcing the 96-year-old’s death, Jozef Hrdlicka, the Czech Communist Party leader declared: “In the end Bilak had to be tied to his bed. His family was left to care for him.” No cause of death was given, but Bilak is believed to have been suffering from dementia.

Bilak was disgraced and kicked out of the Czech Communist party during the country’s Velvet Revolution of 1989, which brought about the collapse of the hard-line Czechoslovak communist regime installed after the Prague Spring some two decades earlier.

A hardliner until the last, he vehemently opposed the reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s enlightened policies of Glasnost and Perestroika during the 1980s. In the 1990s, the new democratic Czechoslovak government sought to try him for treason but the case was dropped in 2011 due to lack of evidence.

Bilak is remembered most for the part he played in bringing about the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the massed troops of the Warsaw Pact on the night of 20 August 1968 – an event that shocked the world.

For 21 years until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the crushing of the Prague Spring served as a potent symbol of Soviet oppression. For regime critics and dissents in the Warsaw Pact countries of Eastern Europe, it was a disaster which crushed hope of reform.

In the West, television viewers were each night shown footage of furious Prague citizens shouting at and sometimes boarding the Soviet tanks patrolling their city with armed Red Army troops astride gun turrets. In January 1969, protest against the invasion culminated with the self-immolation of the Czech student Jan Palach on Prague’s Wenceslas square. In Communist Party circles, including those of the British CP, the term “tankie” was subsequently used to describe those party members who supported the crushing of the Prague Spring by force of arms

The invasion was the Soviet Union’s response to the programme of democratic reforms introduced from January 1968 onwards by Alexander Dubcek, the newly elected and enlightened Czech communist party leader. In a bold experiment, Dubcek began to ease restrictions on travel, media and freedom of speech.

But by August 1968, the Czechoslovak reform process was seen by an already alarmed Kremlin as a direct threat to the future of the Warsaw Pact.

Five Kremlin supporters in Dubcek’s government, including Bilak, willingly put their signatures to a letter inviting the Soviet Union to invade. “The very existence of socialism in our country is threatened,” claimed the letter addressed to then Soviet leader, Leonoid Brezhnev. It asked him to use “all means you have at your disposal to help.” On 21 August 1968, Prague was invaded by Soviet tanks. Bilak was the last surviving communist to have signed the letter.

The late Russian President Boris Yeltsin was clearly so ashamed by the Bilak letter that in 1992 he gave a copy of it to his then counterpart, Vaclav Havel, the late dissident Czech playwright who became the country’s president after leading the Velvet Revolution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments