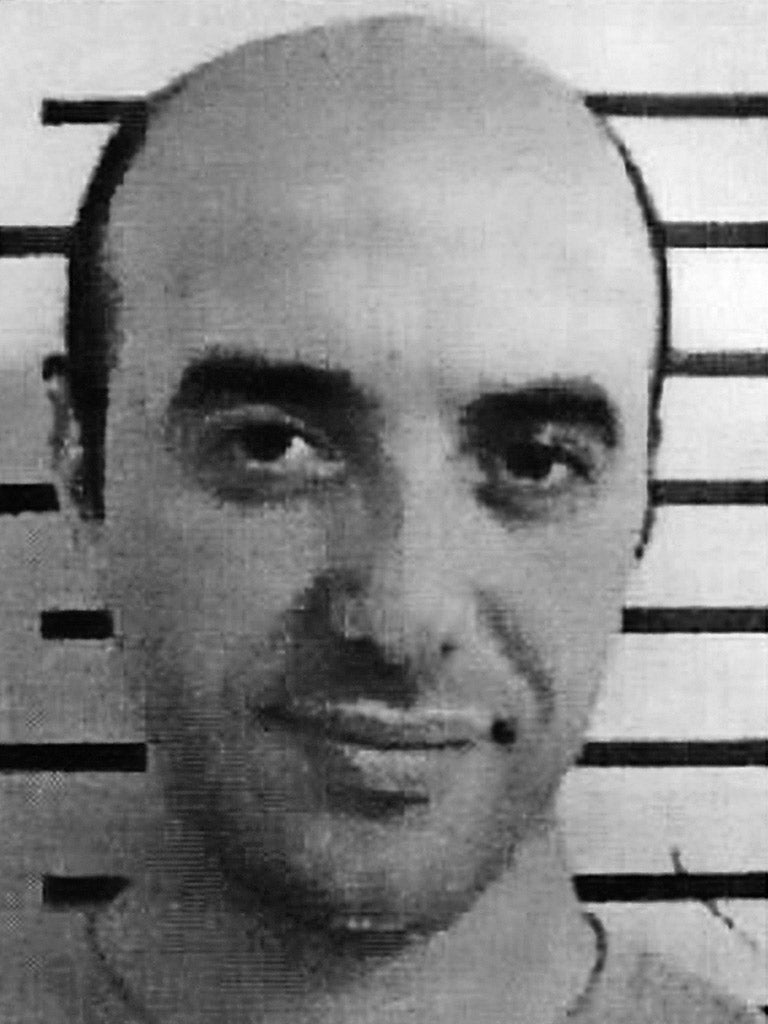

Rédoine Faïd: The Hollywood-style helicopter jailbreak of the robber whose crimes imitate the movies

Smooth-talking criminal got out using a hijacked helicopter and may be trying to get to Israel

During his brief foray into an alternative career as a charming, sharp-suited “reformed robber”, TV studio guest and movie consultant, Rédoine Faïd once said: “I see everything in CinemaScope”.

He certainly staged his second jailbreak with a proper appreciation of Hollywood production values.

It was all over in 10 minutes: at 11.15 on Sunday morning a hijacked helicopter appeared above the supposedly escape-proof Prison de Réau near Paris, opened seven years ago by then French president, Nicolas Sarkozy.

The helicopter hovered very low over the one courtyard in the whole jail that did not have anti-aircraft netting.

Two hooded men jumped out, dressed all in black, with police armbands on their sleeves and Kalashnikovs in their hands.

A third armed man remained in the helicopter, with the terrified pilot, who had begun the morning expecting to give a flying lesson and now found himself cast in the role of unwilling getaway driver.

Seeming suspiciously well-informed about the layout of the prison, the two men on the ground ran into a walkway used only by guards and only in emergencies – “you could almost say it was a secret passageway,” said a union rep for the prison warders.

Using an angle-grinder to cut their way through the locked doors in their way, they got into the prison visiting area.

Faïd was having a seemingly innocent chat with one of his brothers.

Normally, there would be two prison guards supervising visits. On Sunday, there was just one. Unlike the intruders, the guard was unarmed – a measure to reduce the risk of a fatal shoot-out in the event that an inmate should take a visitor hostage.

Now, though, the guard was powerless to stop two determined armed men using smoke bombs to obscure the view of the CCTV cameras and spiriting Faïd out the way they had come in.

The helicopter lifted off from the courtyard, unmolested by gunfire from any watching guards, who are thought to have been under orders to avoid risking the life of the pilot or having an aircraft crash onto occupied buildings.

France’s justice minister Nicole Belloubet was forced to concede it had been “a spectacular escape [achieved by] an extremely well-prepared commando that may have used drones – spotted by the prison authorities a few months ago – to survey the area beforehand."

The prison union representative Martial Delabroye had to explain, without obvious ironic intent, that the courtyard visited by the helicopter lacked anti-aircraft netting because inmates never went there “except to leave the jail”.

In style as well as substance, it seems that so far Faïd’s escape has been everything the 46-year-old would have wished for.

He may have been born to Algerian parents in a grim housing estate 40 miles north of Paris, but Faïd always aspired to something more glamorous, more cinematic.

In the early 1990s he turned one of his first bank robberies into something like a tribute to the 1991 film Point Break, starring Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze. In the film, the robbers wore rubber masks of former US presidents.

In the real-life French remake, Faïd and his gang disguised themselves as Charles de Gaulle and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, borrowing a line from the film to tell their victims: “Thank you for voting for me”.

A similar homage to Hollywood occurred in 1997 when for a security van holdup, Faïd and his crew donned ice-hockey goalkeeper masks, as worn by the robbers led by Robert De Niro in the 1995 film Heat.

In 2009, during his brief, possibly illusory “going straight” interlude, Faïd met Michael Mann, the director of Heat, and told him he had watched the film more than 100 times.

“I told him that he was my best technical adviser,” Faïd wrote in his 2010 book Braqueur (Robber). “With my mates, we would watch his movie like a training film on what to do, and what not to do, to be a successful bandit.”

Other influences are said to include the Quentin Tarantino film Reservoir Dogs.

“Take away the cinema,” Faïd once said, “and you would have 50 per cent less crime.”

In which context it seems that Sunday’s jailbreak should be regarded as the sequel.

The original came in April 2013. There was no helicopter, but it was still pretty cinema-worthy. While awaiting trial at Sequedin prison in northern France, Faïd pulled a pistol out of a bag, fired a shot in the air and took four prison guards hostage.

The box of paper tissues he was carrying concealed plastic explosives and fuses, which he used to blast his way through four gates to the prison car park and the waiting getaway vehicle.

He spent only six weeks on the run before he was recaptured, but that was long enough for him to be called France’s public “enemy number one”.

Perhaps inevitably, given his apparent feel for what Hollywood wants, Faïd has done everything he can to portray himself as the archetype of the charming high-end robber.

In his own, perhaps heavily-edited script, he began stealing and drug dealing at the age of eight, but was always the “social climber of crime”, destined for better things than petty delinquency. (Better things being increasingly defined as what French criminals call “tirelires à roulettes” (piggybanks on wheels or security vans).

His book made much of his charm, the publicity blurb suggesting that even the cops who hunted him considered Faïd “a nice guy”, and stressing that in the course of all his crimes, he had never spilled blood.

The journalist who co-authored the book with him, Jérôme Pierrat, said that during his first long prison sentence for robbery, between 1998 and 2009, Faïd’s charming, cultivated air won over many guards.

Apparently they saw him as a welcome break from the run-of-the-mill thuggish inmate. Some of them, according to Pierrat, even had dinner with Faïd after he was released, saying their goodbyes with the inevitable quip: “Rédoine, we hope we never see you again.”

That was something of a folorn hope.

French prosecutors have claimed that while Faïd was appearing on chat shows and saying the right things about going straight and avoiding bloodshed, he was also planning attacks on security vans.

They say he was the brains behind a security van raid that went wrong, in May 2010. After the robbers were spotted by police, they led officers on a wild chase along a French motorway.

The thieves shot at the pursuing police, injuring motorists as they did so, and then at Villiers-sur-Marne, southeast of Paris, they strafed a police car, killing officer Aurélie Fouquet, 26.

Faïd was linked to the crime and returned to jail. While awaiting trial for the botched robbery, he made his 2013 escape.

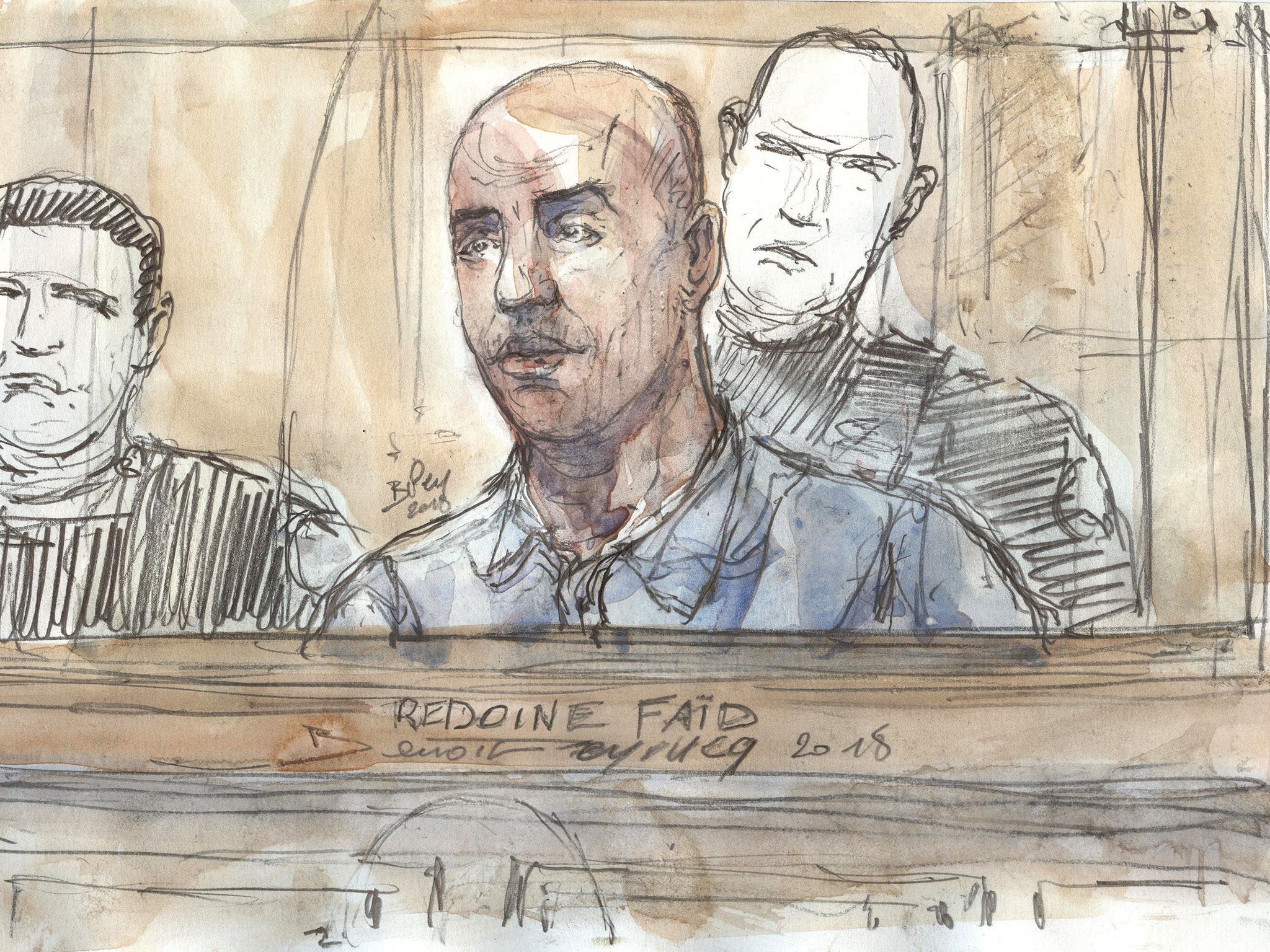

And so, in 2017 he was sentenced to 10 years in jail for the escape and 18 years’ prison for the botched robbery.

In April he failed in an appeal against the robbery sentence – his tariff was instead increased from 18 to 25 years.

By then few were under any illusions about the risk Faïd posed. After all, even when exhibiting the good behaviour that had got him released early from a 32-year sentence in 2009, Faïd had refused to keep a TV in his cell, on the grounds that it would never be his home.

This time round, beginning what was now a 25-year stretch, he was kept on isolation wings and accompanied by a guard wherever he went.

But Laurent-Franck Liénard, the lawyer for Aurélie Fouquet’s family, has now admitted that after 2013: “Not only did I know he would try to escape again, but I was also convinced that he would succeed in the attempt.”

And so it has proved.

Now a manhunt involving around 2,900 police officers, and statements by the French prime minister, has so far recovered the helicopter and taken its pilot to be treated for shock.

They have found the burntout black Renault Megane that Faïd and his accomplices are thought to have used after abandoning the helicopter north of Paris.

They also have CCTV footage of what looks like Faïd sitting on the passenger seat of a small white utility van being driven out of a shopping centre in the northeast Paris suburb of Aulnay-sous-bois.

But they do not have the man himself.

One theory is that Faïd is now trying reach Israel. Despite what some might assume from his Algerian parentage, he does have a fondness for the place.

He has fled there before, after a botched robbery in 1997, allegedly evading police attention by disguising himself as an Orthodox Jew, then learning Hebrew, making friends with the local mafia, and picking up tips on military tactics from an ex-soldier.

But even if Faïd could get to Israel, it remains to be seen whether he could stay there, or keep living the kind of quiet life that keeps a fugitive away from the eyes of the law.

This is a man who once boasted that robbing a security van was “the best of the best”.

For the Hollywood-loving robber, the lure of the tirelires à roulettes and the temptation to recreate some of his favourite gangster movies may yet prove too strong.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments