Romanian prime minister tested in close election

“While the closeness of the election could have an impact on the next government, experts predict that the race might be quickly forgotten”

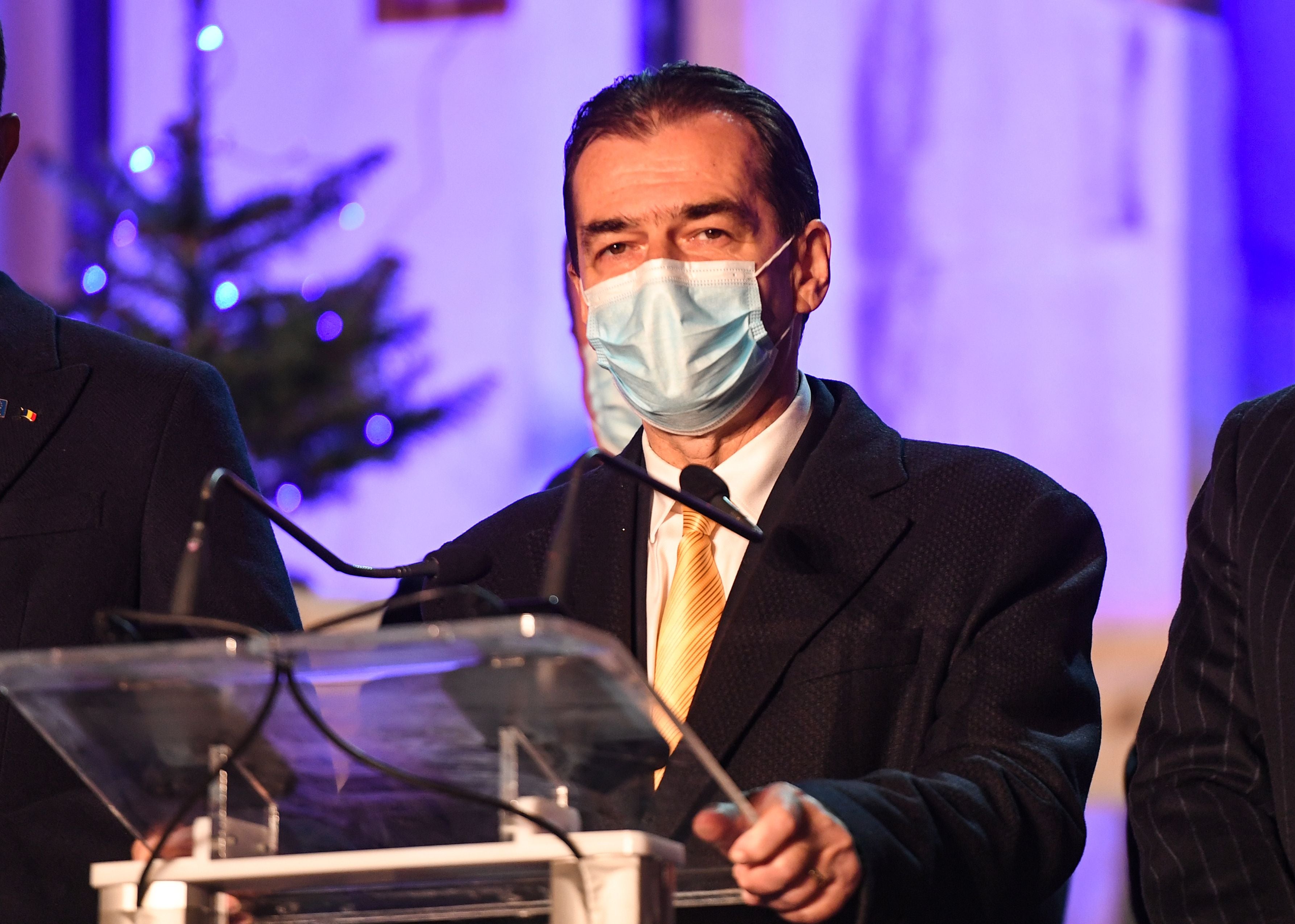

Amid record low turnout, voters in Romania on Sunday dealt a setback to the country’s prime minister, Ludovic Orban, in a surprisingly tight race that threatened his grip on power.

Mr Orban claimed victory Sunday evening, even though his centre-left National Liberal Party was running a close second to its main rival, the Social Democratic Party, in early results.

Mr Orban’s party is expecting that an alliance with a smaller party will help keep it in power. Mr Orban has pledged to continue efforts to modernise the country, one of the European Union’s poorest member states, while also keeping Romania on a pro-European path.

But a strong showing by the Social Democratic Party, which has been accused of a host of political scandals in recent years, and the potential arrival in parliament of a new nationalist party soured the mood for many Romanians. They had been hoping for a clearer sign that the country was putting the past behind it.

The elections were never likely to give a strong majority to any single party.

But the outcome appears to allow a working coalition between two centre-right parties: Mr Orban’s National Liberal Party and an alliance known as USR-PLUS, which appeared set to come in a strong third. Still, they will most likely need to bring in additional coalition partners to stay in power.

Hours before polls closed, Mr Orban urged Romanians to go out to vote.

“Four years ago, low turnout led to a parliament lacking legitimacy, a parliament which undermined the rule of law and democratic institutions,” he wrote on his Facebook page.

But his appeals appeared to fall flat. Turnout was less than 32 per cent of eligible voters, the lowest in the country since the fall of communism more than three decades ago.

Four years ago, after the Social Democrats took office, Romania was convulsed by a series of political scandals.

Vast protests erupted in February 2017 over an emergency decree that effectively decriminalized low-level corruption, and demonstrators denounced long-standing graft in the country. The firing of Laura Codruta Kovesi, the head of Romania’s anti-corruption agency, spurred more protests a year later.

For a while, it had looked as if Romania was following the path of Poland and Hungary and pursuing a more illiberal form of democracy. But in 2019, the Social Democrats’ powerful leader, Liviu Dragnea, was jailed for abuse of office, and the government was toppled after a no-confidence vote in October that year.

In November 2019, President Klaus Iohannis, previously the leader of the National Liberal Party, won a handy victory in his reelection campaign, a further repudiation of the deposed Social Democrats.

In the months leading up to the current election, polls had tightened, with the National Liberal Party experiencing a fall in support amid criticism of its handling of the coronavirus pandemic. Romania, which has imposed relatively strict lockdown measures, has registered more than 500,000 confirmed cases of the virus, with more than 12,000 deaths.

Sorin Ionita, a political analyst at the Bucharest-based research group Expert Forum, said that the Social Democrats’ approach under Mr Dragnea had an obvious impact on last year’s presidential election but that “low turnout and the party getting rid of the toxic team around Mr Dragnea” gave the party a stronger public image.

In a statement after polls had closed, Mr Orban said that his party considered itself to be “both the moral winner and the winner at the end of the counting process,” and that it would be able to quickly form a parliamentary majority.

Romania has experienced a conveyor belt of governments and cabinets in recent years, with five prime ministers in five years. Mr Orban’s minority administration lost a no-confidence vote this year, but ultimately remained in power to avoid political uncertainty in the face of the pandemic.

While the closeness of the election could have an impact on the next government, experts predict that the race might be quickly forgotten.

“Once they are in and form a coalition, it will be very stable for the next four years,” said Mr Ionita.

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks