Spanish women protest against new laws limiting the availability of abortions

Females across the country are queuing up (and sometimes lying down) to oppose legislation which will limit the availability of abortions. Alasdair Fotheringham in Madrid asks what these so-called registry protests can achieve

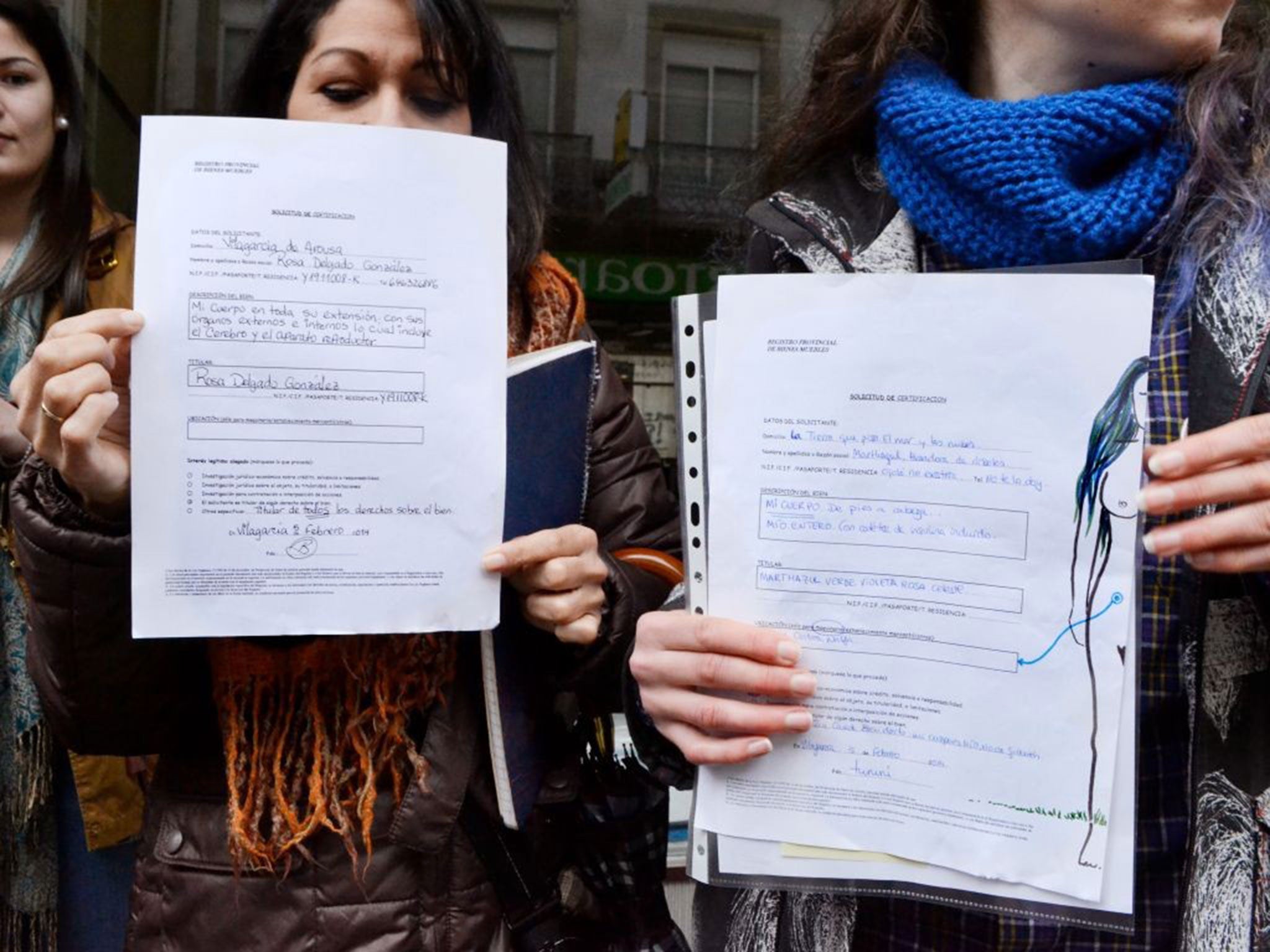

As havens of humdrum state bureaucracy, government commercial registry offices are rarely targets for demonstrators. But this month, queues of women have lined up outside offices across Spain to demand that the largely baffled civil servants within allow them to symbolically register their bodies as their own property, with official certificates to prove it.

From Bilbao, Madrid and Barcelona to Pontevedra and Alicante, the so-called “registry protests” are the latest attempt by women’s rights activists to draw attention to controversial government plans to dramatically limit access to abortion – a move that would create some of the strictest anti-abortion laws in Europe.

“We are saying, ‘If you don’t treat us as real people but as objects then okay, we’ll go to the commercial registry office and have our bodies officially denominated as “property”. Yolanda Domíngez – the Madrid-based artist and activist who originally conceived the “registry protests’” – told The Independent.

Since 2010, Spain has allowed women to seek an abortion up to the 14th week. But the planned changes to the law would make the procedure illegal, except in rape cases, or where two doctors independently certify that a failure to abort would damage the women’s mental or physical health. The governing People’s Party – backed by the Catholic Church – is adamant that access to abortion should be curtailed, with Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy repeatedly pointing to his party’s electoral manifesto, which promised to “ reinforce protection of the right to life” for the foetus.

Yet activists say if the law is changed, it would huge step backwards for Spain, putting the law on par with some of the strictest anti-choice legislation in the world and would violate women’s rights over their own bodies.

For Ms Domíngez, the amendments are characteristic of “the way women have been treated and dictated to for years, right down to how we have to behave, think and look.”

Thousands of people have taken to Spain’s streets to protest against the proposed measures in recent weeks, with hundreds more heading to the registry offices to take a stand. Such broad-based sympathy for the protesters is perhaps unsurprising, given a 2012 survey showed roughly 80 per cent of Spaniards, including practicing Catholics, believe the planned changes to the current abortion law are unnecessary.

In the past week, three regional parliaments – Catalonia, Extremadura and Andalusia – have voted against the reforms, as have the town councils of around 200 municipalities, some run by the ruling Partido Popular (PP) party. Demonstrations have been held not only in Madrid – where tens of thousands protested against the law – but also outside Spanish embassies in Brussels and Paris, where people symbolically demanded “asylum” in France from the new laws. Tickets for a “freedom train” earlier this month, which transported hundreds of activists from northern Spain to a protest in Madrid, sold out rapidly and the radical Femen group have carried out several protests, the latest surrounding the archbishop of Madrid as he was entering a church. They chanted “Abortion is sacred”.

However, speaking at the PP convention earlier this month, Justice Minister Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón insisted the amendments would go ahead.

“You have my word that no screams or insults could provoke me to abandon my commitment to comply with the [party] platform to regulate the rights of women and the unborn,” he said. “We are not talking about moral issues or electoral advantages, but instead the defence of fundamental rights.”

Analysts say politics plays its part in the controversy. The party is keen to boost support among its socially conservative base voters before May’s European elections, especially as many are said to be deeply upset by the PP’s failure to rein in Catalan and Basque nationalists and reduce taxes. Within parliament itself, there seems to be only the barest murmur of dissent amongst the PP’s rank and file. A secret vote on the law’s reform in Madrid last week was regarded by pro-choice activists as a golden opportunity for deputies to rebel against their leadership. Instead, even without the fear of their identities being disclosed, 183 MPs voted in favour of reform – three less than the PP’s total number of deputies. The Opposition, with 151 votes against, were clearly defeated.

The activists, meanwhile, pour scorn on the government’s arguments and assert they are defending women’s fundamental rights.

“[This] would be the first time they’ve carried out one of their electoral promises,” May Serrano of the Mujeres Imperfectas [Imperfect Women] collective, which organised the registry protest in Bilbao. “This law represents a return to [the philosophy of] ‘ Ladies, go back home, have children’. It’s as if we were still living in caves.”

Ms Domínguez believes the proposed reforms are fuelled by the misconception that some women “abort on a whim” and therefore stricter controls are needed to prevent all terminations except in extreme cases. “Nobody ever does that: it’s a traumatic, risky experience and it’s a very tough decision to have to make,” she says. “It strikes me as absolutely absurd that somebody who has no idea about my personal situation decides what I can or can’t do with my body.” Many activists say there are many other, less drastic, steps to reduce the number of terminations. Under Spain’s current, pro-choice legislation, Ministry of Health figures showed that in 2012, the number of women undergoing the abortion procedures dropped five per cent from the previous year.

Yet with the government adamant to press on with the changes, the protests are set to continue.

Ms Domínguez says she has been surprised by the way support for the ‘registry protests’ has “mushroomed”. In Madrid, several female civil servants have asked for application forms to register their own bodies. “I’ve even had emails from parents who want to go and register their daughters,” says Ms Domínguez. As Spaniards continue to endure the after-effects of the country’s two year recession, and the PP faces long-running allegations of corruption, Ms Serrano says she believes the government’s resolve on this particular issue – in the face of such public opposition – can only backfire.

“Up until last year feminism was an old-fashioned word in Spain, and that’s no longer the case,” she says. “On top of that people [these days] are asking a lot more about what society in general is doing for them. And the less they have to lose, the more they will ask that.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks