Ten years on, Italy still split over Craxi

Establishment tries to rehabilitate memory of Berlusconi's disgraced mentor

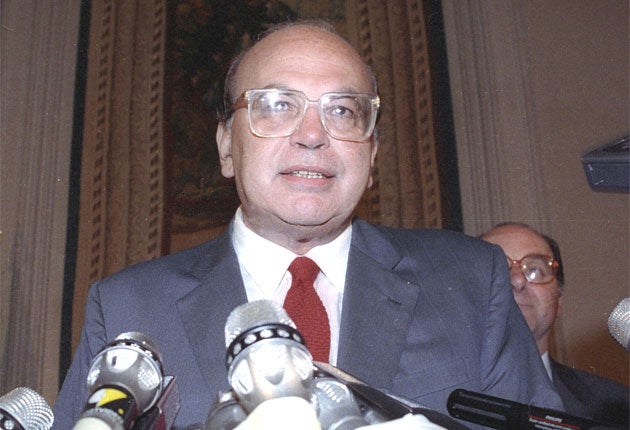

In a remarkable turnaround, Italy's political establishment yesterday came together to celebrate the life of the former Socialist Party leader Bettino Craxi, exactly 10 years after he died in exile as a convicted criminal and the man most widely blamed for Italy's pervasive political corruption.

In what became known as the Mani Pulite ("Clean Hands") scandal, Craxi was accused of taking bribes worth millions of pounds. The source of the biggest bribe, worth more than £10m, was a company called All Iberian, which was founded by his close friend and protege Silvio Berlusconi.

Craxi's cavalier defence, "cosi fan tutti" – "everybody does it" – failed to impress the public and he was showered in coins as he left his hotel in Rome, a treatment traditionally reserved for thieves. Disgraced, Craxi fled to his villa in Tunisia to avoid going to jail. He was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in his absence, and died in exile on 19 January 2000.

But now to the delight of many, including Mr Berlusconi – though to the disgust of many others – the rehabilitation of Bettino Craxi is proceeding apace. Milan's right-wing mayor Letizia Moratti, the education minister in a previous Berlusconi government, has announced that a road in the city will be named after him. And at a ceremony in the Senate, Mr Berlusconi and some of his ministers joined Craxi's relatives in celebrating his life. Lamenting the treatment he received, one senior Berlusconi ally said: "For Craxi there was no mercy. He paid more than anyone else for things that were part of the political system of the time."

Even President Giorgio Napolitano, a former communist, appeared to fall in with the new mood, remarking that Craxi had left an "indelible mark" on Italian politics.

But Antonio Di Pietro, the judge-turned-opposition politician who interrogated Craxi in December 1994, was forthright in his condemnation. "We're not providing a calm reappraisal of those years, but falsehood and distortion," he said. "He received treatment different from other people? Well yes, in the sense that he was without equal in the way he behaved, and in the manner of his crimes and those he allowed to be committed."

Felice Belisario, an MP in Mr Di Pietro's Italy of Values party, said: "This beatification of a convicted criminal in an institutional setting like the Senate is really shameful." Demonstrators paraded with posters, showing the two leaders' faces merged, reading "Berluscraxi".

The Clean Hands corruption investigation sprang from the arrest in February 1992 of Mario Chiesa, a close associate of Craxi who was caught pocketing a bribe, before it quickly spiralled out into the political and business worlds.

Investigators uncovered a huge web of corruption, and the Christian Democrat and Socialist political establishment were swept away by the mood of public disgust. Within two years, 321 MPs had been investigated, and eight ex-MPs and around 5,000 businessmen were charged with corruption following the suspension of general parliamentary immunity – which Mr Berlusconi is now seeking to restore.

Although he became a symbol of corruption, Craxi's reputation as a vigorous and decisive leader continues to overshadow his crimes in some quarters. He earned the soubriquet of Europe's strong man when he refused the request of US President Ronald Reagan to extradite the Arab hijackers of the cruise ship Achille Lauro to stand trial in the US in 1995.

Mr Berlusconi, making his first official state appearance since being attacked in December, yesterday paid homage to his old friend in the Senate, leading observers to ruminate once again over the nature of their relationship. Craxi was Mr Berlusconi's patron when the latter was a budding media tycoon: he became godfather to two of Mr Berlusconi's children, and forced through the laws that enabled Berlusconi to break the monopoly of public broadcasting and set up Italy's first commercial television network in the mid-1980s.

The trials that led to Craxi's flight from justice were supposed to purge Italian politics of corruption, but 17 years on few would claim they have had that result. Luca di Montezemolo, the chairman of Ferrari and Fiat, claimed recently that nothing had really changed since the scandal-torn years of the early 1990s.

Bettino Craxi: The socialist fugitive

* Born Milan 1934, the son of a lawyer.

* In 1983, he became Italy's first socialist prime minister. He ruled until 1987, making him the longest-serving post-war Italian premier – a record overturned only by his friend Silvio Berlusconi in 2005.

* During the abduction of the former prime minister Aldo Moro in 1978, Craxi was the only important MP to call for talks with the ultra-leftist Red Brigades who seized him. No negotiations were initiated and Moro was killed by his abductors.

* While prime minister, Craxi proudly announced that Italy's gross domestic product had overtaken that of the UK.

* The 'Berlusconi Decree' of 1984 was the greatest favour he performed for the young media tycoon, breaking RAI's TV monopoly and allowing Berlusconi to set up a private network in competition with it.

* As the bribery scandal sprialled out of contro, Craxi resigned as secretary of the Socialist Party and fled to Tunisia, where he remained until his death seven years later.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks