The Family Man of Amstetten: Double life of a pillar of Austrian society

How did the perpetrator of one of modern Europe's most horrific crimes convince his neighbours he was a respectable man? By David Randall

He was a very good family man, was Josef Fritzl. In his home town of Amstetten just eight days ago, they'd have been adamant about that. Hadn't he brought his seven children up to be good boys and girls? Always so polite; just like their father. And when that silly daughter of his ran off to join this religious cult, had he bothered people with lots of questions about who she'd been seen with recently? No. Even when the little hussy had three children and just dumped them on his doorstep, did he complain? No. He just took them in and raised them as if they were his own. And he was always so smart. He had pride, did Fritzl. He really was a very good family man.

And then, everything began to change. On Saturday 19 April, a girl of 19 had been taken seriously ill at 40 Ybbstrasse. As luck would have it, this was Josef Fritzl's house. He found her, and called an ambulance. She was taken to Amstetten hospital, where doctors saw she was very pale and bleeding from her tongue. Then, an hour after her admission, Fritzl arrived and saw Dr Albert Reiter. He told him that the girl's mother, his daughter Elisabeth, was unable and unwilling to look after her and had dumped her at his house. She had, he said, left a note. This said that the girl, Kerstin, had suffered headaches, taken an aspirin, and then begun suffering convulsions, hence the bleeding tongue. Then Fritzl went away. After all, he had his own family to look after.

The girl got worse. The fits continued, she lapsed in and out of consciousness, and her immune system did not seem to be working. Doctors issued an appeal for her mother to come forward and tell the medical history of this mysterious patient, but there was no response. A week went by. Kerstin deteriorated. By now she was on a ventilator, and in a medically induced coma, with her kidneys functioning artificially. But still no mother came.

Then, last Saturday, 26 April, Elisabeth Fritzl appeared on the streets of Amstetten for the first time since her disappearance. She was with her father and heading towards the hospital. When they reached the grounds, the police, tipped off that they were on their way, detained them. So poor was Kerstin's condition (she had lost nearly all her teeth, was excessively pale and severely malnourished) that they wanted to question her mother with a view to bringing charges of child neglect.

They took her to a room and began to talk. Right from the start, there was something very odd about her. Apparently only 42, she looked, with her grey hair and almost white complexion, like an institutionalised woman in her sixties. She was nervous, too, and suddenly asked if they could guarantee she and her children would never again have to see Fritzl, this helpful, polite man who had brought his daughter's note and then his daughter to the hospital. And then she told them a story that even now, eight days after its telling, beggars belief.

Elisabeth had not run away to join a cult. Instead, her father had been beating her since she was old enough to walk and sexually assaulting her since she was 11. When she was 18, he had drugged her, dragged her to a concealed cellar in his house, raped her, and gone on doing so for the next 24 years. For nearly a quarter of a century, she and three of the seven children that were the result of those rapes, had lived in a windowless netherworld. The children had never seen the outside world or breathed its air. They knew neither freedom, nor the rest of society. And the only person they had seen was their jailer, the man who would alternately play with them and terrorise them, who told them if they tried to escape they would be gassed in their chamber, who raped their mother and yet, with his boxes of groceries and meals shoved through a hatch, was their only lifeline: the good family man of Amstetten.

The history of Josef Fritzl begins on 9 April 1935 with his birth in the town he was to make notorious. Most of his first 10 years were spent under the Third Reich, and a Franz Fritzl is listed on Amstetten's war memorial, but the town council refused last week to say if this was Josef's father. Fully five days after Fritzl was arrested, Colonel Franz Polzer, the chief investigator for the Austrian police, said: "I don't even know who his parents were." That lack of knowledge, even a seeming reluctance to thoroughly seek it, is a theme that echoes and echoes through the Josef Fritzl story.

The fleeting certainty in his biography begins when he finished his schooling. First, he studied electrical engineering at a polytechnic school, then took a job with steel company, Voest. It was in his early days there, in 1956, when he was 21, that he married 17-year-old Rosemarie and started a family of seven children with her. From that point, the facts of his business life become patchy. From 1969 to 1971, he worked for Zehetner, a construction materials firm in Amstetten, where he was described as "an intelligent worker and a good technician".

After that he was a travelling salesman for a German company, and, in 1973, he and his wife bought an inn and summer campground in the mountains, which they ran until 1996. And at some point the man who already owned a large greying townhouse in Amstetten (and which he eventually filled with eight tenants) got into property, buying further houses.

All the while, his family was growing. Rosemarie was born in 1961, then Ulrike, Doris, Harald, Elisabeth in 1966, and twins Josef Jnr and Gabriele in 1971. Outwardly, all was well. Josef Fritzl was the smartly dressed engineer who drove a Mercedes and had such well-behaved children. But now we know that even before he dragged his daughter off to spawn the subterranean brood, he was showing signs of a freakish criminality. Its details are clouded by a seeming lack of official curiosity.

There is, for instance, his reported conviction for rape: either of a woman in Linz in 1967, or, around the same time, of a nurse in her flat. Officials earlier said they knew of no record of such a conviction, and that one of such age would have been expunged long ago by laws designed to rehabilitate criminals but which are also part of an informal masonry that has sped "good chaps" with murky pasts back into respectability.

But, by Wednesday, a woman told reporters: "I was raped by Fritzl. When I saw his picture yesterday, I knew, yes, that is him." Her attacker broke into her home, held a knife to her throat, and raped her in her own bed. On Friday, officials said a rape file had been found and is being studied. Linz police, it now turns out, also recorded him as a suspect in two other sex attacks, and in 1974 and 1982 he was investigated for arson. There is also the unsolved matter of Martina Posch, whose body was found in 1986 in a lake near the inn the Fritzls owned. Martina, 17, who had been raped, bore a striking resemblance to Elisabeth.

Inside the home, too, the domestic martinet – not an unknown character in provincial Austria among men of that age – was something altogether more ugly. In 1977, when Elisabeth was 11, he began to sexually assault her. The girl, already an outsider at school, became more withdrawn. Her best friend then, Christa Woldrich, said Elisabeth always had to be home half an hour after school finished, and added: "I was never allowed to visit her. The only explanation she ever gave was that her father was very strict. I did not see him, but he was always there between us because of his influence over her, like an invisible presence you could always feel."

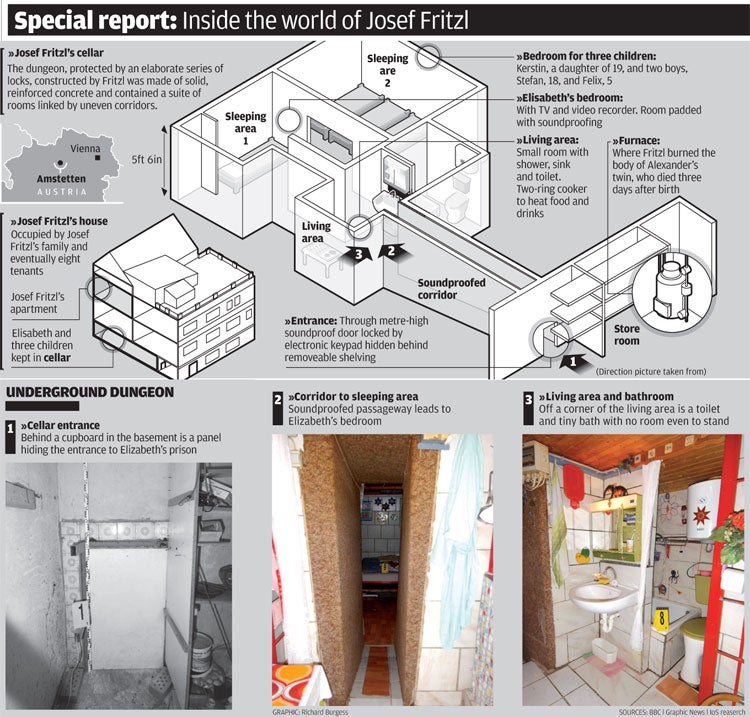

A year after the molesting of Elisabeth began, Josef Fritzl applied for planning permission to turn his basement into a nuclear shelter, as many did in those Cold War years. He worked on it over the next five years, installing a steel door (it is thought, with some help, for it weighed 661lbs), and officials came and approved what he was doing in 1983. They even gave him state funds towards its construction. Why not? After all, ever the good family man, he was only building a shelter for his wife and children.

But it is possible that he was, all along, planning the newly secured quarters as Elisabeth's underworld prison. For the victim of his assaults was now showing a wilful desire to break free. Twice as a teenager she ran away. Twice she was found and brought her back. Twice no one inquired if there were some reason for her wanting to get away from home so badly. As with Fritzl's criminal record, best, perhaps, not to ask.

But whenever the scheme to capture Elisabeth was first conceived, in 1984 he put it into effect. One night in August, he sedated his 18-year-old daughter, and hauled her down to his basement and over to a cupboard. He moved this to reveal a 3ft-high door, took her and himself through it, and so into the cramped and primitive rooms that were to be her sole environment for the next 24 years. He raped her, and then manacled her to an iron pipe, returning every so often to feed her and repeat the rape. Up above her head, her mother Rosemarie reported her missing, and fretted and worried about what could have become of her – until Josef, good old reliable Josef, told her the girl had run off to join a religious cult. After all, he told everyone, had she not run away before?

For the next five years, Elisabeth lived here alone, her entire universe consisting, at its largest, of 60sq yards, defined by 5ft 6in-high ceilings and guarded by an electronically operated steel door. She was as trapped as an insect in a jar. No windows, no books, no sun, fresh air or rain; just a few bare rooms in a bunker and a bed upon which to be raped.

Then, in 1988, she fell pregnant. The world her father had built for her not only lacked pity, it lacked doctors. And so, the following year, her first child was delivered in her dungeon by the man who was her father, her captor and her rapist. It was a girl and she called her Kerstin.

Gradually, over the years, this grotesquely conceived family expanded: Stefan in 1990, Lisa in 1992, Monika in 1994, Alex in 1996 (he had a twin who, dead at three days, was thrown by Fritzl into the cellar incinerator), and then Felix in 2002. Three of them, Lisa, Monika and Alex – the "cry babies" who he feared might attract attention with their mewling – were taken upstairs and "found" by Fritzl, some with notes saying their mother could not deal with them. And the good family man agreed to adopt one and foster the other two.

Over the next dozen or so years, childcare officials visited the Fritzls at least 21 times, and, despite his criminal record, his daughter running away twice, his incessant absence when they called, and the mysterious regularity with which babies appeared on his doorstep, they consented to the legal niceties on the grounds that Josef and Rosemarie were "family". Indeed they were. His own flesh and blood, in every appalling sense.

The other three children remained underground with Elisabeth. In time, Josef extended their dungeon, and spent hours down there at a time, sometimes whole nights, playing with or terrorising the children, chatting to, or raping, their mother. And when he wasn't there, he was buying and selling property, acting the paterfamilias, giving his wife the rough end of his tongue in public ("We don't have sex any more; she's too fat"), and going twice on lengthy holidays to Thailand, venue of choice for perspiring men who no longer have sex with their wives. Police were not impressed with such information. "His holidays," said Colonel Polzer, "are none of our concern."

A companion on the Thai jaunts was "Paul H", one of the few friends who visited Fritzl in his home, most recently in 2005. "The children were all scared stiff in the presence of their dad," he told Germany's Bild, "They were never allowed downstairs into the cellar, but we never thought anything of it." Fritzl's tenants were even warned that if they ever strayed near the cellar, or took photographs of it, they would be summarily evicted. In another place such an exclusion zone would have invited curiosity. But not here.

And, occasionally, a letter would arrive from what the rest of the family assumed was their errant daughter and sister, Elisabeth. "Do not search for me," began one, "it would be pointless and would only increase my and my children's suffering. Too many children and an education are not wanted there." Even without hindsight, it is odd that Elisabeth's mother, her adult sisters or brother seem never once to have mounted an effort to find the author of this distressing note.

The years in the dungeon – so easily summarised in a paragraph, so dreadful endured in dank reality – went on in their seasonless way. In 1999, Kerstin was 10; three years later she was a teenager with a new baby brother, and the following year Stefan reached 13. Did he, one wonders, even know how old he was? For this was a life measured not by days and nights, routines and holidays, but only by the rotting of another tooth, the greying of their mother. Upstairs, time was measured. In 2006, Amstetten honoured the Fritzls for reaching their golden wedding. Such a good family man, Josef.

But his secret family was beginning to hang heavy on Josef Fritzl. Around Christmas 2007, he got his daughter to write another letter. It seems that Fritzl, bored by the daily chores – the shopping, the rubbish burning – and no longer beguiled by a daughter who now resembled a woman of his wife's age, was preparing the endgame. At some point, he would stage-manage the release of Elisabeth from the cult that had held her this past quarter of a century, and she would return to the house that she had, in reality, never left.

But Kerstin's illness aborted that plan. As the 19-year-old grew increasingly sick in a cellar whose only medicines were aspirin and cough mixture, Elisabeth pleaded with her father to take her to a hospital. When the girl fell unconscious, the weary Fritzl agreed. Within a week, Elisabeth was making her revelations to the police.

The two remaining underground children, Stefan, 18, and Felix, five, were released that Saturday evening, and so saw for the first time a world they had previously only ever seen on television. They gazed in awe at the moon, and, although they shrieked with excitement as the police car set off, they flinched every time a vehicle went past, thinking it was about to hit them. The following morning, at the Mostviertel Clinic, extraordinary encounters: the boys meeting their above-ground family for the first time, and their mother the children – Lisa, Monika, and Alex – she had not known since they were babies, and the mother she had not seen since she was a teenager.

The clinic's director, Berthold Kepplinger, said: "The two women fell into each other's arms and wept bitterly. They held each other and did not want to let go." The older just said: "I'm so sorry. I had no idea."

It will take more than hugs to repair the damage done to this family, especially the underground part. Stefan and Felix, say police, cannot speak normally, and use mainly growls and coos to communicate with each other. Mr Kepplinger said: "The one who seemed most distressed was Felix. He'd jump and start at the slightest disturbance and held on to his mother the whole time." Going in a lift especially frightened him, although, according to police chief Leopold Etz, he has moments of joy, and then "he slaps the air with his hand when he can't control his excitement". The older boy is hunched after living in only the low-ceilinged cellar, and both of them and their mother suffer from chronic vitamin D deficiency.

Therapy of a different order might well be delivered on Fritzl himself when in due course he is given a taste of being behind a heavy locked door that does not open from the inside. There are conflicting reports about his mental state – defiant, say police; a broken man says his lawyer – but they seem immaterial. Either way, he's not giving much away. The only group of people who are talking freely are assorted former tenants. Alfred Dubanovsky has been the most voluble, saying of the cellar: "He used to take food and shopping down there in a wheelbarrow at night. Other times I could sometimes hear a knocking from the cellar I couldn't explain." Best, of course, not to ask.

Meanwhile, the big questions go unanswered: did his wife (whom police have not yet interviewed) know? Or did he latterly let someone in on his dread secret? There have been reports that one of Elisabeth's brothers had access to the cellar. Six officers are now in the cellar looking for evidence. It would have been worse if Fritzl had not had a confidant. Long past the age when men have heart attacks and strokes, imagine if he had keeled over before his captives had been released. A coronary, perhaps, as he pawed a little Thai prostitute in a Pattaya parlour? Or a fatal seizure as he walked to his car under the weight of the extra groceries. What then? A funeral with his widow and seven children and three "grandchildren" in weeping attendance; local traders turning up to pay their respects, and a few old lads from the fishing club come along to salute their fellow angler. And, afterwards, a few eats and drinks at the Fritzl house.

All the while, beneath their feet, Elisabeth, Kerstin, Stefan and Felix Fritzl would have been slowly starving to death, their hammerings and shouts insulated. How long would it have been before their skeletons were found? Ten years? Twenty? Or maybe never.

Their imprisonment – in three cases their very existence – dying with the respectable old engineer who was, his town would have told you, a very good family man.

What next?

Kerstin Fritzl: Now feared to be losing her fight for life, as she lies in Amstetten hospital with multiple organ failure two weeks after her admission.

The investigation: Police now searching cellar for traces of DNA of any possible accomplice. After that, they will bring in sonar equipment to look for more hiding places. Officers can work only one hour at a time because of the severe lack of oxygen. Police will also question more than 100 people who lived in Fritzl's house during his daughter Elisabeth's captivity, and others who say they knew him.

Elisabeth and her children: Being cared for at clinic, which has provided them with a confined space similar to cellar into which they can retreat. Will require years of therapy, and the older children, and Elisabeth, may never lead normal lives. Authorities offered to give them, and other members of the clan, new identities.

Josef Fritzl: Held in custody facing charges of incest, rape and false imprisonment. Also a possible "murder through failure to act" charge in connection with baby who died in the basement – and, with Kerstin, too, if she dies. Links to other sex crimes being examined. So far has said little, save to admit fathering the children, and that he imprisoned his daughter to "save her from drugs".

Austria: The President has proposed, in order to restore the nation's image, that most modern of elixirs: a public relations campaign. Others have urged Austrians "not to look the other way" in future.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments