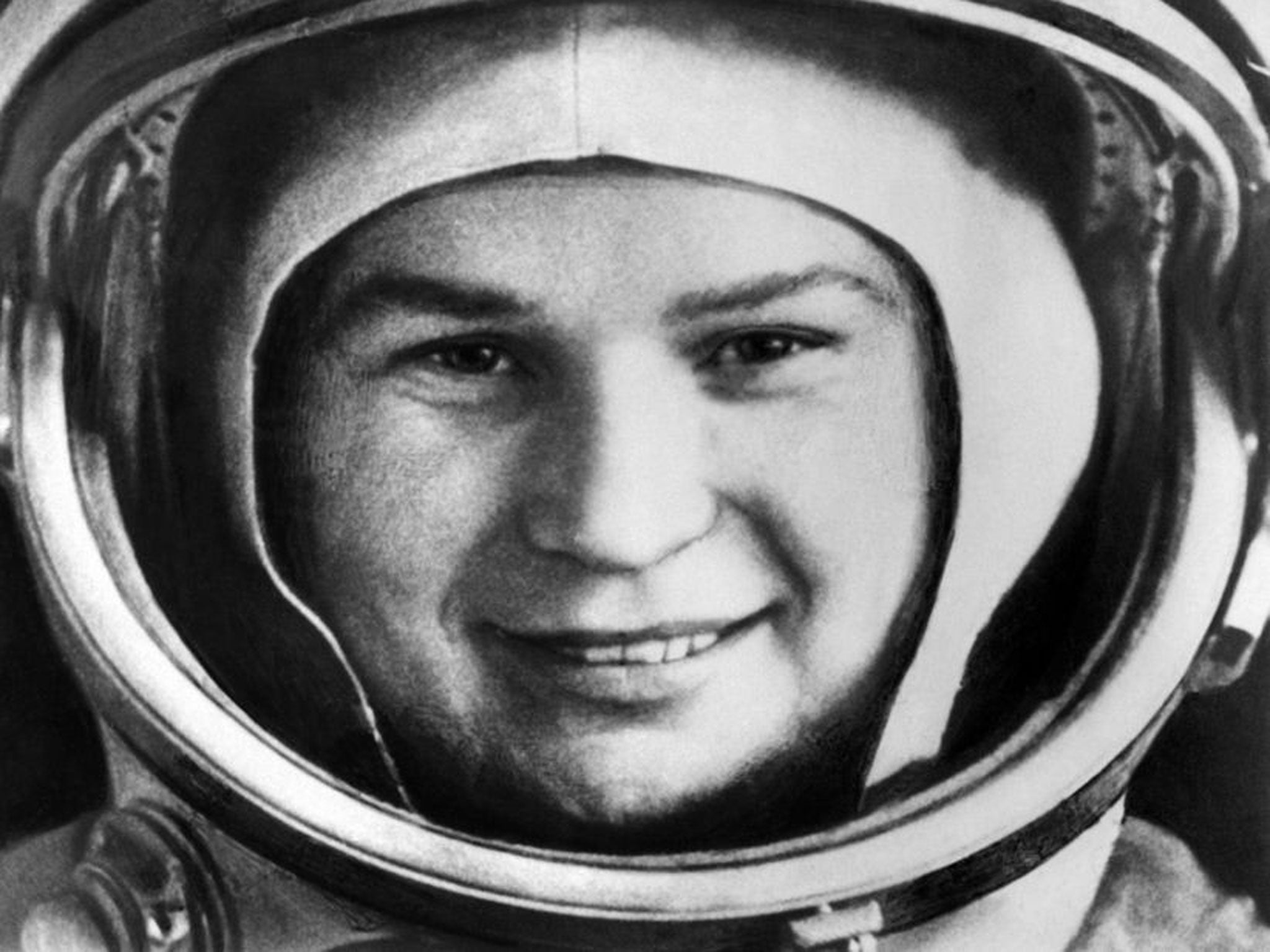

The first female cosmonaut: Valentina Tereshkova - The woman who fell to earth

Valentina Tereshkova, the first female cosmonaut, is now an MP for Putin’s party. But he wouldn’t like what she says about communism

Fifty years ago, Valentina Tereshkova was about to become the most famous woman in the Soviet Union.

Having won the race to put the first man into space, when Yuri Gagarin blasted into orbit in 1961, Moscow also succeeded in sending a woman into space for the first time on 16 June 1963.

Tereshkova, selected from a field of over 400 candidates, was launched from the obscurity of a textile factory worker in her home city of Yaroslavl, into space for nearly three days. She returned, having orbited the earth 48 times, to be fêted as a true Soviet superstar.

Half a century later, Tereshkova is still seen as a heroine in Russia. She is still promoted by the government as a symbol of Soviet and – by extension – Russian achievements. She does not enjoy interviews, unsurprisingly perhaps for someone who has spent half a century being honoured for the same achievement, and very rarely speaks to the media.

Nevertheless, her popularity and status is still a powerful tool. Now 76, she is an MP for President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia Party, and was yesterday awarded a prestigious award for public service by Putin personally.

The Russian government’s PR service helped to arrange a rare interview for The Independent, but when she appears she does not seem too happy about the fact.

“What do you want from me?” she growls in a weary voice, as she emerges from the conference hall where Putin’s new Popular Front movement is taking place, and a gathering of priests, army generals, politicians and flag-waving youths has been singing the national anthem and giving repeated chants of “People! Russia! Putin!”

She cancels the planned lengthy interview, and instead offers a 10-minute chat on the street next to a busy pedestrian underpass near Red Square, as Muscovites and tourists bustle past. An aide crouches down to hold on to her skirt to ensure it does not blow up in the wind, and she occasionally interrupts the interview to take calls on a gold-plated mobile phone.

Nevertheless, when asked about preparations for her flight, she immediately brightens up. “We were all young, we were just burning with desire to go to space,” she says. The provisional group of 400 women was narrowed down to just five, all of whom began an intensive training programme.

“We were all amateur parachutists, but we weren’t pilots, so the main thing was to train us as pilots. Nowadays, space crews have different people to do different tasks, but back then you had to be the pilot, the engineer, the doctor and the navigator.”

At the time, a lot of things were unclear about how a human body might react to prolonged space travel. There was little of the psychological preparation given to those who go to space today, though she was kept in a silent chamber for hours on end to prepare her for the solitude of space travel.

The nearly three days she spent in orbit amounted to more than the combined flying time of every American astronaut that had flown up to that point.

“You don’t think about the danger,” she says of her flight. “The spaceship becomes your home.” She has previously denied reports that she became unconscious in space and repeatedly vomited.

She remains friends with the other four women who were not selected, and says they meet up regularly. “Probably they were jealous of me,” she concedes. “But they never said anything.”

On landing, she was taken to hospital, and, after a number of tests and medication, was driven triumphantly through Moscow in an open-top limousine garlanded with flowers, to Red Square, where she waved to the assembled masses from atop Lenin’s mausoleum, alongside the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who would later preside at her wedding to another cosmonaut, Andriyan Nikolayev.

“I dreamt of flying again, but sadly it never happened,” she says. Instead, she became an advertisement for the success of the Soviet space programme, featured on postage stamps and immortalised in monuments. She also became a political figure, appointed to the Central Committee of the Communist Party, and was the first female general in the Soviet armed forces.

She has denied that her marriage was arranged by the Soviet authorities, who wanted to see a perfect “space couple”, but she and Nikolayev divorced in 1982, and it is clear the hero worship has caused her distress over the years. “I never aimed to be on television or in the press,” she says. “We all have a personal life and being a public figure disrupts that.”

Yesterday, Russian news reports featured footage of Tereshkova being driven through Moscow in an open-top limousine again, this time to the monument to Yuri Gagarin, where she laid a wreath in memory of the first cosmonaut, before travelling to Putin’s dacha to receive her award.

She spent her 70th birthday in the company of Putin several years ago, and mentions that in 2010, when there were no funds available to finish the construction of a planetarium in her home city of Yaroslavl, she personally appealed to the Russian leader. “He helped us out and we built it, and now it’s one of the most popular places in Yaroslavl,” she says.

Despite her strong patriotism, she believes that international co-operation is very much the future of space travel. “Back then, it was all about competition of course.

“We didn’t have rest days or weekends, because we had to get ready as fast as possible, so we could beat the Americans, who were also racing to send a woman into space. But now, the only way forward in space travel is for everyone to work together.”

Even back in the Soviet period, she says there was a certain bond between cosmonauts and astronauts. “The Westerners came to our training facility in later years, and they felt that special brotherhood we have,” she says. “It doesn’t matter what country or what political system you are from. Space brings you together.”

She has great nostalgia for the Communist superpower that she helped win such a key victory in the space race. “Just as for everyone who remembers the Soviet Union, it is a deep personal tragedy for me that it collapsed,” she says.

“It was a great tragedy for all the people. But now we are living in new times, and we need to do everything to make Russia a great country again.”

This, she says, is why she supports Putin so wholeheartedly.

“I support him in absolutely everything he does. He wants to make our country one of the most important in the world again, and to improve the lives of everyone in it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments