628-year-old fake news: Scientists prove Turin Shroud not genuine (again)

Forensic analysis of possible bloodstains suggest marks could only have been made by someone adopting different poses, not dead Messiah lying still in tomb before the resurrection

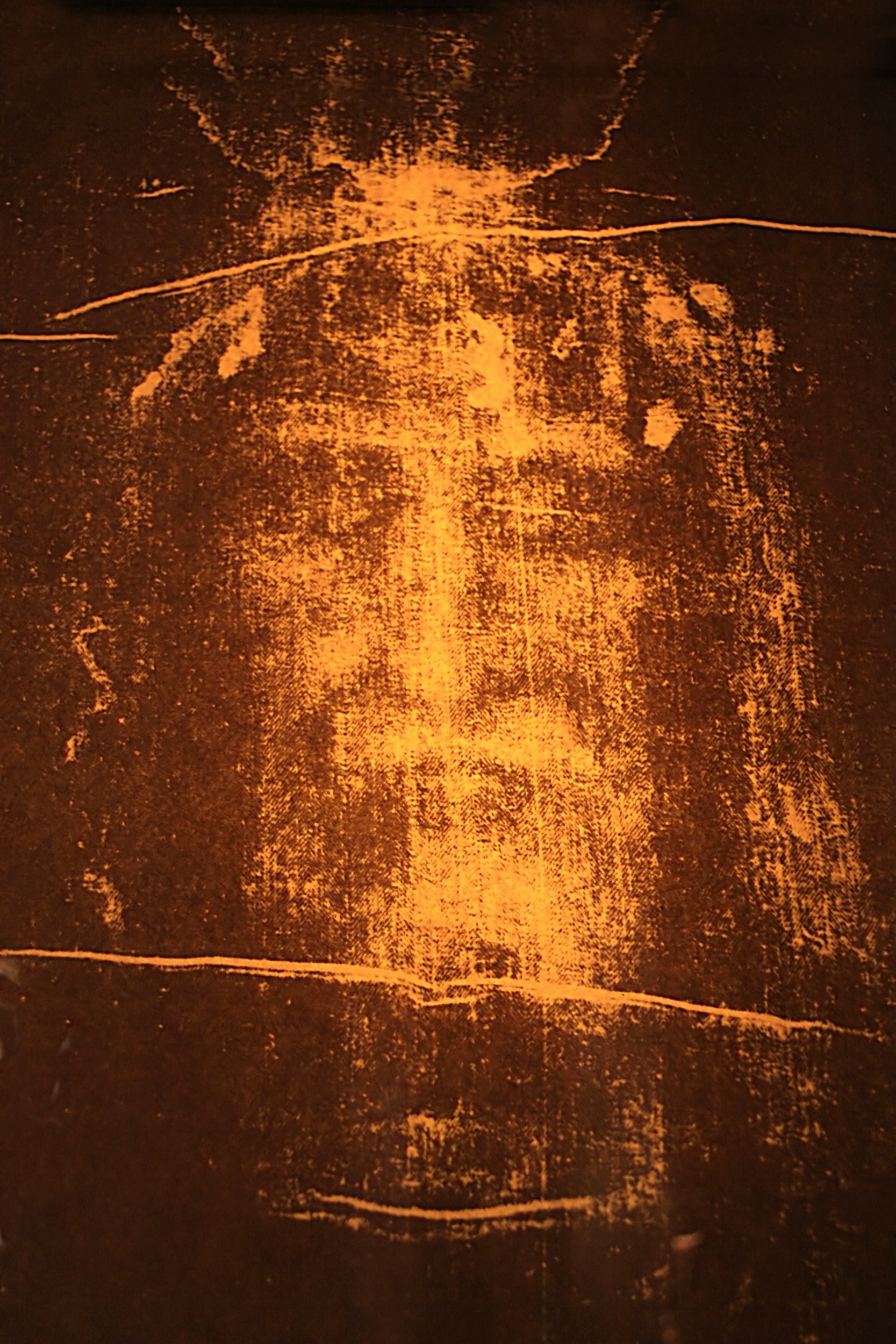

The Turin Shroud is a fake.

That is the verdict of Catholic Bishop Pierre d’Arcis who has written to tell the Pope it was “a clever sleight of hand” by someone “falsely declaring this was the actual shroud in which Jesus was enfolded in the tomb to attract the multitude so that money might cunningly be wrung from them”.

Admittedly, since Bishop d’Arcis was writing in 1390, to Pope Clement VII rather than Pope Francis, this is not exactly new news.

But since some have refused to believe the bishop’s findings, or the 1988 carbon dating showing the shroud was from the medieval, not the Biblical era, or the subsequent debunking of claims disputing the carbon dating, scientists today are still studying the Turin Shroud.

And they are still concluding it is fake.

In the latest, but almost certainly not final instalment, they have used modern forensic techniques to show that apparent blood spatters on the shroud could only have been produced by someone moving to adopt different poses – rather than lying still, in the manner of a dead and yet to be resurrected Messiah.

Forensic scientist Dr Matteo Borrini of Liverpool John Moores University and Luigi Garlaschelli of the University of Pavia used a living volunteer and real and synthetic blood to try to simulate possible ways that the apparent bloodstains could have got onto the shroud.

They concluded that two short rivulets of possible blood on the left hand of the shroud’s ghostly figure could only have been formed by someone who was upright with their arms at an angle of about 45 degrees.

This could be consistent with someone who had been crucified with their arms held in a Y shape. Unfortunately for shroud believers, however, the forearm blood stains would require the dead body to have been wrapped in the shroud with their arms in a different position – held almost vertically above their head, rather than at an angle of 45 degrees.

The researchers, whose findings have been published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences, formed the opinion that the supposed blood spatters seem to have fallen vertically and almost randomly from someone who might well have been standing over the cloth, rather than lying in it.

When it came to the supposed lance wound, their article A BPA [Blood Pattern Analysis] Approach to the Shroud of Turin concluded: “The BPA of blood visible on the frontal side of the chest (the lance wound) shows that the shroud represents the bleeding in a realistic manner for a standing position while the stains at the back—of a supposed post-mortem bleeding from the same wound for a supine corpse—are totally unrealistic.”

Dr Borrini is himself a Catholic – albeit one who does not need the shroud to bolster his faith.

It remains to be seen, however, whether it will shield him from the criticism of those who are convinced the shroud made its way from Jesus’ Jerusalem tomb, to Constantinople in 944, to Greece after the Sack of Constantinople by Crusaders in 1204, to France, and eventually to Italy.

The shroud, bearing what looked like the double image of a man who had been crucified, is now in the royal chapel of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin.

But it was while it was in France, soon after the start of what is sometimes called its “undisputed”, or documented history, that Bishop d’Arcis became one of the first people to express doubts about the 4.4 m (14ft 5in) long and 1.1 m (3ft 7in) wide piece of linen cloth.

Writing in 1390, the bishop said that the cloth first started attracting pilgrims in 1355 when it was in the possession of the Geoffrey de Charny, a French knight building a church at Lirey to give thanks to God for a miraculous escape from English imprisonment during the Hundred Years War.

D’Arcis told the pope that his predecessor as Bishop of Troyes, Henry of Poitiers, had fairly quickly discovered “the fraud” and obtained a confession from the artist who produced it that it was “a work of human skill and not miraculously wrought or bestowed.”

It is fair to say that when d’Arcis wrote about the shroud still being used as a moneyspinner in 1390, he was a bit angry.

“I cannot fully or sufficiently express in writing the grievous nature of the scandal,” he told Pope Clement VII. “The Dean of a certain collegiate church, to wit, that of Lirey, falsely and deceitfully, being consumed with the passion of avarice, and not from any motive of devotion but only of gain, procured for his church a certain cloth upon which by a clever sleight of hand was depicted the twofold image of one man …

“And further to attract the multitude so that money might cunningly be wrung from them, pretended miracles were worked, certain men being hired to represent themselves as healed at the moment of the exhibition of the shroud.”

Even in 1355, d’Arcis told Pope Clement, medieval experts were debunking the claims being made about the shroud.

The bishop recalled that during Henry of Poitiers’ investigation “Many theologians and other wise persons declared that this could not be the real shroud of our Lord having the Saviour's likeness thus imprinted upon it, since the holy Gospel made no mention of any such imprint, while, if it had been true, it was quite unlikely that the holy Evangelists would have omitted to record it, or that the fact should have remained hidden until the present time.”

Some modern commentators, however, have dismissed Bishop d’Arcis’ comments as nothing more than jealousy and synthetic outrage.

They say he just wanted to discredit the shroud so all those free-spending pilgrims would visit his cathedral at Troyes, rather than the church at Lirey.

Perhaps more difficult to dismiss than medieval bishops was the evidence of 20th Century scientists from the University of Oxford, the University of Arizona and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, who were allowed to carbon date samples of the shroud in 1988.

After three separate tests in laboratories in Arizona, Oxford and Zurich, the scientists stated with 95 per cent confidence that the shroud dated from 1260-1390, (a date range which happened to include the first documented references to the cloth).

The ensuing 1989 paper Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature, seemed to leave little room for doubt by stating: “The results provide conclusive evidence that the linen of the Shroud of Turin is medieval [not Biblical]”.

Counter-arguments, however, were marshalled - In 1998 it was reported that the office of Anastasio Alberto Ballestrero, the former Cardinal Archbishop of Turin, had issued a statement suggesting the carbon dating had somehow been interfered as a result of an "overseas Masonic plot"

There were more science-based objections to the carbon dating results, but they tended to be met with what looked like further rounds of scientific debunking.

The Turin Shroud Centre of Colorado suggested carbon monoxide could have altered the shroud’s radiocarbon age to make it seem much younger. It was, however, pointed out that this would have required unnatural concentrations of a gas that doesn’t normally react with linen, and that no such contamination has ever been observed.

Some shroud believers suggested the carbon dates fragments may have included part of a 16th Century attempt at ‘invisible’ repair of a shroud dating from the time of Christ.

This garnered the response that if the scientists really had tested samples that combined 16th Century and first Century elements, they would have got a carbon dating reading of around the 7th Century – still much earlier than the actual results obtained.

The 1988 carbon dating was also questioned on the basis that the fragments tested had been contaminated by modern material.

Scientists, however, believed that the different cleaning procedures at the three laboratories would between them have removed all possible contamination. Independent scientists also said the cleaned cloth would have needed to stay heavily impregnated with modern carbon for the results to be so skewed that a 2,000-year-old shroud was dated to the 13th or 14th Century.

It may or may not be of additional significance that successive popes have tended to use their words carefully when it comes to the Turin shroud.

Pope Francis has described it as an “icon of a man scourged and crucified” – all very reverential, but significantly short of calling the shroud a “relic”, which would imply a belief that it really was Christ’s burial shroud.

Even so Turin’s Museo della Sindone, (the Most Holy Shroud Museum) continues to attract healthy visitor numbers, and when the shroud itself was briefly put on public display in 2015, more than a million people went to see it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks