Meeting the refugees in Kos: A first-hand account of the people behind the headlines

Fresh from a crisis in her own life, C L Bell felt unable to ignore the plight of refugees arriving in Greece. So when she travelled to Kos, it was less a holiday, more a quest to understand our imperfect empathy for our fellow humans

The police station overlooks the sea. A crowd is queuing outside, spilling on to the street. A policeman, dressed in black, is shouting: "Get off the road!"

When the people don't move, his anger grows and he begins pushing, first with his hand, then his truncheon. He is not hurting, just prodding, but his energy is sharp.

A Syrian man in the queue holds up his hands. "Please!" he says. Tourists stop to watch. A young teenage girl sits on the sea wall, staring out to sea. A middle-aged British woman walks up to her and fishes €10 out of her handbag. "I'm sorry," she says. "We are not doing enough." The girl looks surprised, but accepts the money and wipes a tear from her eye.

This is Kos.

Like most of us living in Europe in 2015, I had become familiar with news reports of refugees crammed into half-sinking boats being rescued by steely-grey coastguard ships. Unlike earlier footage from Syria of screaming bodies burnt by bombs and the blurred videos of beheadings – scenes that were so far from my reality, they only pushed the conflict further away – the shots of these women walking in orderly file affected me deeply because I recognised the look on their faces: relief.

Twenty-first century Europe may be billed as the Promised Land, but it is as incapable as ever from shielding us from sickness, death and despair. Over the previous four years, I had watched my husband disintegrate physically and psychologically as he battled two kinds of cancer, and then watched with cautious hope as he slowly edged back towards health. In those women's faces, I recognised my own. In their relief, I was able to connect with their suffering.

I thought of them daily, imagining the desperation and fierce will that made them prepared to risk death rather than continue at home. Then, on an internet clip, I watched three men arriving ashore in a yellow dinghy on the Greek island of Kos. With their heads bowed, they clambered out, tore at the boat that had carried them, before stumbling off into darkness.

I went to a map and found Kos. It is one of the most southerly of the Greek islands. I carried on looking until I found Skopelos, one of the most northerly, and then I breathed a different sigh of relief. I, too, was planning an escape – from a winter that was refusing to end, from my husband's frustration with his still ailing body, from our newfound infertility.

I needed to lie in the sun and be quiet, and the thought of coming face to face with refugees as I fled my own life filled me with a complex mix of aversion, guilt and shame. It got me wondering: how do we care for someone else's suffering when we are overcome by our own? How do we care when we cannot? I knew I would not find the answers staring at a screen, and then on Wikipedia I read something that made up my mind. A citizen of Kos is called a Koan – the same word used in Zen Buddhism to describe a paradox used to move the mind towards enlightenment and greater understanding. I would take my Koan to Kos.

Fifteen miles off the coast of Turkey, Kos is one of the Dodecanese islands. All summer, 500–900 people have been arriving daily. They come ashore in the early hours of the morning in inflatable boats built for six and packed with 40. The wealthy stay in hotels, the poor sleep rough while they wait for police to issue papers to permit them onward travel to Athens. From there, most hope to reach Germany.

"Hey, love, just seen news. Let me know you are safe." It was 11 August, 10pm. I had just left Kos airport.

I asked my taxi driver what it was about. "Humph," he said with half a sigh, half an uncomfortable laugh. "Kos is special place. We have ancient monuments that we must protect, and these immigrants, they are everywhere, leaving rubbish, going to toilet. We cannot. Today we moved them into the stadium."

"And there was a protest?" I ask.

"Yes, some got angry, but it is calm now."

A few days later, I will learn that the police moved those camped in the main tourist area into the football stadium, and locked them in. Outside, men began throwing stones at police cars. A Pakistani man threatened a policeman with a knife and the policeman slapped him. By 3pm, Athens had flown in 200 riot police and by 4pm the situation had been defused. The heavy-handed policeman was suspended. Later that night, the Daily Mail reports, in its own heavy-handed way, that "the holiday island descended into a battlefield".

"What can we do?" sighs the driver. "Here in Kos, we have two more months to make money that must last us the year."

His voice is not angry. It is a weary voice. This has been Greece's annus horribilis. The economic crisis that began in 2009, plunging 44 per cent of Greeks below the poverty line by 2014, came to a head in June when Greece defaulted on a $1.7bn sovereign debt repayment to the international monetary fund (IMF). Crisis talks in July saw Greece reluctantly signing a deal that would bind them to the eurozone and to debt repayments that critics say will extend the country's economic misery indefinitely.

"I feel sorry for the people running from war, I really do," the taxi driver says. "The people from Syria must run for their lives. But those from Pakistan and Afghanistan, they do not belong here."

"How can you tell the difference?" I ask.

"You can see. The Syrians, they come with families. The others come alone. Young, dark-faced, skinny men. We do not trust them."

"What do you think should be done?" I ask.

"Stop saving them at sea. We have to let two or three boats drown." He pauses for a moment, seeming to regret his words.

"It is not a solution I like. There are women and children. But they will only stop coming if they are afraid. Now, they are not afraid."

I am not sure. I felt anxiety when I left home this morning. No matter how often I go away, I always feel this way. To leave your world for a week is unsettling. But to leave your world for ever, how can we understand? I check in to a cheap hotel in the back streets of Kos town, where low buildings crowd along cracked, unlit pavements. As I walk alone to a late-night restaurant, I kick something underfoot. A cat stirs. Should I be afraid, I wonder? And then I smile. Why would someone fleeing war want to hurt anyone? If they wanted violence, they would have stayed home. I am on an island of sun-worshippers and peace-seekers.

I wake early after a night thick with dreams. The Kos quayside is already bustling. Bronzed bodies jostle for the best spots on board wooden boats bound for nearby islands. Wrangly men, the kind the taxi driver described, walk past in groups. Families, all with dusty shoes, pass by, looking for somewhere to wash.

At a quayside coffee shop, I notice three women in white hijabs and sit down. The coffee costs €3.50. Am I presumptuous to think they are refugees? Then I see them waving. A teenager and a young boy holding an orange life jacket walk towards them. One woman pats the boys on the arm to reassure them. The young one tries to smile, the older boy collapses his head on the table, exhausted. I feel my eyes moisten. This is happening.

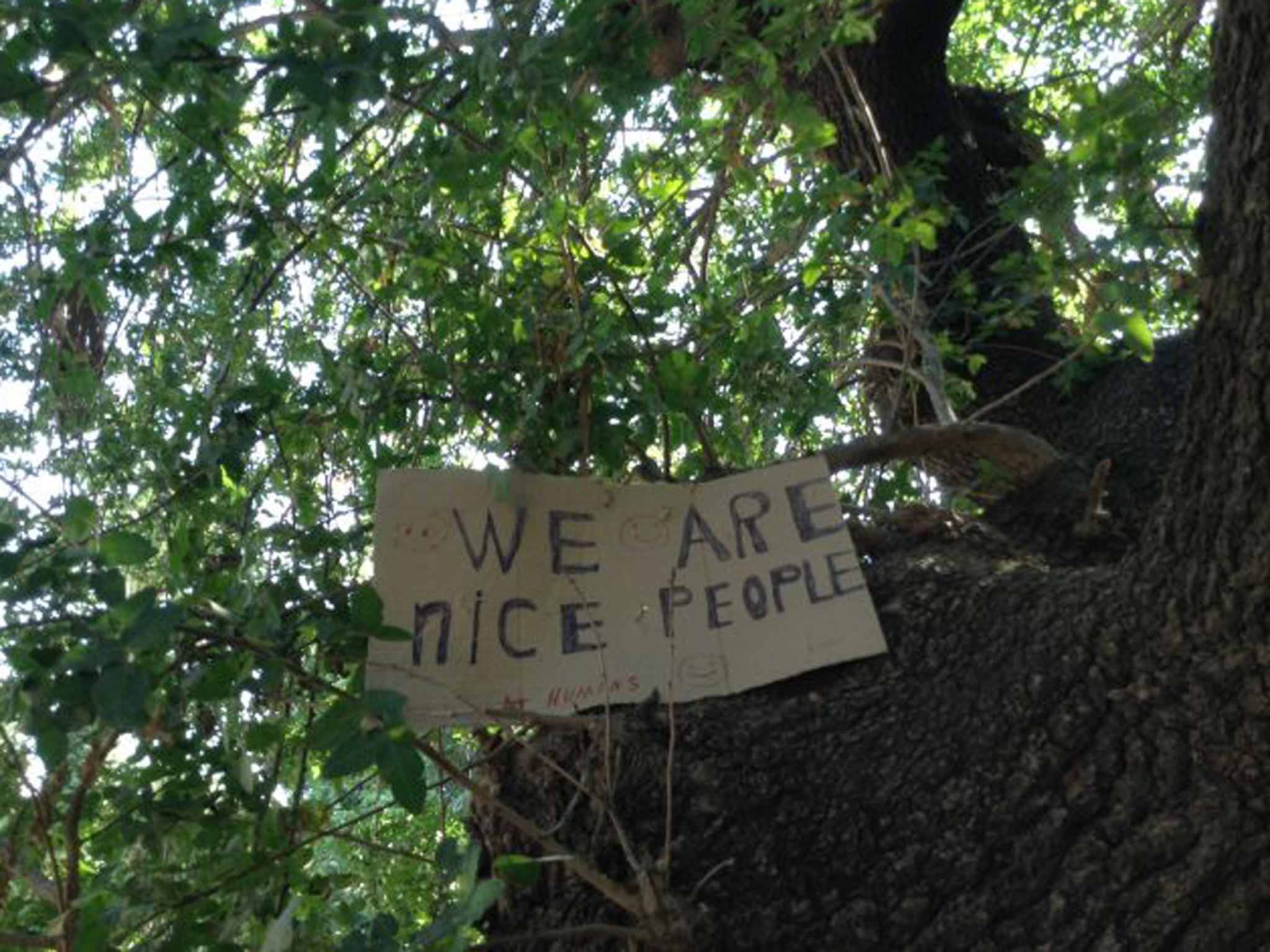

I walk on. I follow a sign for the Plane Tree of Hippocrates, where the father of Western medicine once taught healing. The approach is up stone steps, through a shady courtyard. Two days ago, people camped here. Tucked in a tree I notice a cardboard sign: "We are nice people. Humans." A few families are sitting on benches. A young boy is wearing a yellow T-shirt with the maxim: "Don't Let Life Get You Down". "Good T-shirt," I say. He smiles shyly. I sit under the tree of Hippocrates. "First do no harm," that was his teaching. 2500 years later, we have still not mastered it.

I keep walking. I follow people behind an old stone wall. Inside is a shady park, the trees strung with washing, people sleeping. It leads to Agora, one of Kos's archaeological sites. At the far exit, I notice a woman begging, holding a cardboard sign: "I want to return to Bulgaria." I feel a flash of irritation. Bulgaria is part of the EU. She is not fleeing war. I have not seen one refugee begging. Everyone is walking quietly, with purpose, queuing to buy bread, milk, water. They ask only for papers, a safe passage, a chance to build a new life.

Away from the tourist centre, tents begin to reappear in quiet neighbourhood parks, and along the promenade, shaded by palm trees. Family after family, not knowing where they are going, their only certainty that they cannot return. I think of the expression "my heart goes out to you", and the words make sense, because that is how it feels, as if my heart is pulling out of my chest.

I had wondered, how can you care when you think you cannot? Now, I understand. My heart is much bigger than my mind. "As-salamu Alaykum," I say to people who look my way. Peace be with you. Smiles come to their faces. "Wa-Alaikum-Salaam," they reply.

I stop to talk to four young Syrian men. "I feel bad, this small," says Abdalrahem, 26, an engineer. "People think we are beggars, but we are university graduates. We cannot stay in our country any more. Now, if you are not Daesh [Isis] then you are a kafir [disbeliever]. Break their rules and they will cut off your head."

I ask if they regret the revolution. "No, but I regret the weapons," says Abdalrahem. "We should have stayed peaceful."

After a few hours, I return to my hotel and call my husband, a former war correspondent with The Times. As I hear his voice, I start to cry. "You're too soft," he says. "You wouldn't make a foreign correspondent." Maybe. Or maybe this is how it feels when you see people fleeing from war. In the hotel lobby, I ask if there are any refugees staying at the hotel. The owners points out Hiba Ezzideen, a fair-haired 29-year-old Syrian from Idlib, with a masters degree in English. Around her neck is a gold necklace engraved with the words: "Free Syria". I ask her to tell me her story.

"Before the revolution, in Syria, it was like living in a big prison," she says. "The economic situation was not that bad, but the best jobs went to the Alawites – Assad's people." She remembers how the revolution started peacefully. "Silently, we held up cards that said 'We Need Democracy'." And she recalls Assad's first bomb attack. "We heard an airplane in the sky and we saw the shells dropping on Jabal Al-Zawiya, a nearby town. We thought it was Israel. It seemed impossible that your own government would attack you."

It was partly this thought that had made me cry. I am a child of a nanny state and a rainbow nation. Born in the UK, but raised in South Africa, I came of age with the oration of Nelson Mandela that championed freedom and equality. There is no denying that, 20 years later, there are deep cracks in our rainbow nation, but the root of our complaint is similar to those I hear daily in my adopted home in Scotland: that our governments do not care enough about us – not that they are systematically killing us.

Pro-democracy youths rallied to form the Free Syrian Army (FSA) to fight back against the government, but by the end of 2012, there was a radical change in the nature of the conflict. "The FSA was hijacked by the salafi, the radical Muslim groups including al-Qaeda and Isis, who think only Muslims should inhabit the Earth. It started to become an Islamic war."

By 2013, Hiba's village was under the control of Isis. She recalls the first time she saw a beheading. "I was in my car, stuck in traffic. I wondered why we weren't moving and then I saw it. It was like watching a film. After that, it became normal."

She started a Facebook page to document Isis crimes. In 2013, using her smart phone, she filmed them cutting off the hand of a man and uploaded it. That night, she received a message: "Lady, we know who you are and we are going to kill you." She fled for the countryside near Aleppo, and continued her campaign until in 2014, with more threats to her life, she fled to Turkey and then to Kos.

"We walked for hours to reach the boat," she remembers. "I was with a Kurdish family and I asked them for water. The Arabs look down on the Kurds. We think we are better than them. But they gave me water, and in that moment, I saw that they are nice people. And I saw how I had treated them before."

On the beach in Kos, Hiba met an American who had come to the island to escape his own tragedy – his parents had been killed in a car accident. "I feel like my life has no meaning," he told Hiba, adding how the refugees crisis was only adding to the angst. Hiba counselled him. "I said, on this beach there are 100 people, 100 stories. They all matter. It is only politics that is dirty. It doesn't care about human lives."

I join Hiba for a simple dinner and discuss her onward plans. "I want to walk to Holland," she says.

"All the way?" I ask

"I want to go as far as I can. I want this experience." Her own Santiago de Compostela. A pilgrimage to a new life. "I think wars are good, because they remind you to search for the immortal things to believe in. And for me, that is humanity."

The next day I head, by bike, to Captain Elias, a disused hotel where refugees have been camping. On the way I chat to four Bangladeshi men, squatting in the shade. "Is there war in Bangladesh?" I ask. They shake their heads. "So why do you come?" I ask.

"Bad life there," says one.

"And where will you go?" I ask.

"Paris," he says.

I ask them if they realise how hard it will be. Even the French are struggling to find work. I feel I am bursting his bubble. "If it doesn't work, we will go back to Bangladesh."

I stop for a coffee. Nickos, the Greek waiter, estimates that there has been a 30–40 per cent drop in tourism. But he does not bear a grudge. "Sometimes you have to look further than your own back yard. It is just a shame this didn't happen 10 years ago. We could have coped better." At the squatted hotel, I meet Africans from Cameroon, Mali, Nigeria and Congo. We talk in French. Foben Mohammed, 34, had an IT business in the north of Cameroon that was destroyed by Boko Haram. Christian Wawa, 39, is from Kinshasha in Congo. Above his left eye and into his scalp is a deep, jagged scar – an attack with a machete. "I am running from Kabila," he says, referring to Joseph Kabila, the President of the Democratic Republic of Congo. This year, there has been nationwide unrest sparked by a parliamentary Bill viewed as a crooked attempt to extend Kabila's rule. "If his people find me, they will kill me."

They all say they thought they would have better reception in Greece. "Look at this place. They don't care about us. I have been here for one month already. They process the Syrians' papers in a few days, but they make the blacks wait," Foben says.

"This life is too much, too hard," Christian says, his eyes filling with tears. "Sitting here all day, it makes you bad in your head."

"Do you think Europe owes you refuge?" I ask. Foben nods. "They must accept us because every time the Europeans come to Africa, they have houses, cars, good jobs. Everything is okay for the European in Africa."

It is lunchtime and the men insist that I share their lunch. When I protest, they protest. "You are from Africa, you must eat with us," Foben says. They offer me a chair and we gather around a makeshift table. "Where do you think black people will be the most welcome?" Foben asks.

"London. Berlin. The big cities," I say.

I ask Foben what he would say to a young man planning the same journey. "I would say don't come – it is too difficult."

They ask about my life and I tell them about a book that I have written. In South Africa, I explain, despite our rainbow nation, there is still mistrust between the races.

White women are told not to travel alone to rural villages, and so I wrote a book in which I did that, facing up to the fear, ignorance and prejudice in me.

"What is the book called?" asks Christian.

"Lost Where I Belong," I say. "Perdu Chez Moi."

Christian's eyes fill with tears again. "Comme moi," he says. "Like me."

A version of this article originally appeared on medium.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments