Crossing a desert wilderness in the footsteps of Britain’s forgotten explorer

A small team of camels and walkers will set off from Oman today to recreate the first crossing of the Rub al-Khali, the world’s largest wilderness of sand

When Bertram Thomas woke on Oman’s coast 85 years ago, he did so with failure looming over him. A steamship sat in harbour waiting to take him back to the city of Muscat where castigation and a letter of dismissal from London awaited him. Then he saw the sight for which he had been waiting – a straggly line of 15 camels and their desert-hardened Bedouin keepers.

Within 60 days, the Englishman and his remaining Omani companion had turned ignominy into gritty triumph by emerging some 800 miles (1,300km) further north in what is now the Qatari capital of Doha. Together they had conquered by foot one of the world’s last wildernesses – the Rub al-Khali, the forbidding “Empty Quarter” of the Arabian Peninsula.

Such was the scale of the achievement by Thomas, who had departed in complete secrecy knowing that official permission for such a journey would never be permitted, that it made front page news from London to New York. Among the adulatory telegrams was a missive from George V offering “hearty congratulations”.

History has thereafter largely forgotten the achievements of the Somerset-born sailor’s son. Thomas’s pioneering journey has been overshadowed by the better-known adventures of swashbuckling British Arabists such as Wilfred Thesiger and Lawrence of Arabia.

It was TE Lawrence who recognised the singular nature of Thomas’s feat. He wrote: “We cannot know the first man who walked the inviolate earth for newness’ sake; but Thomas is the last.”

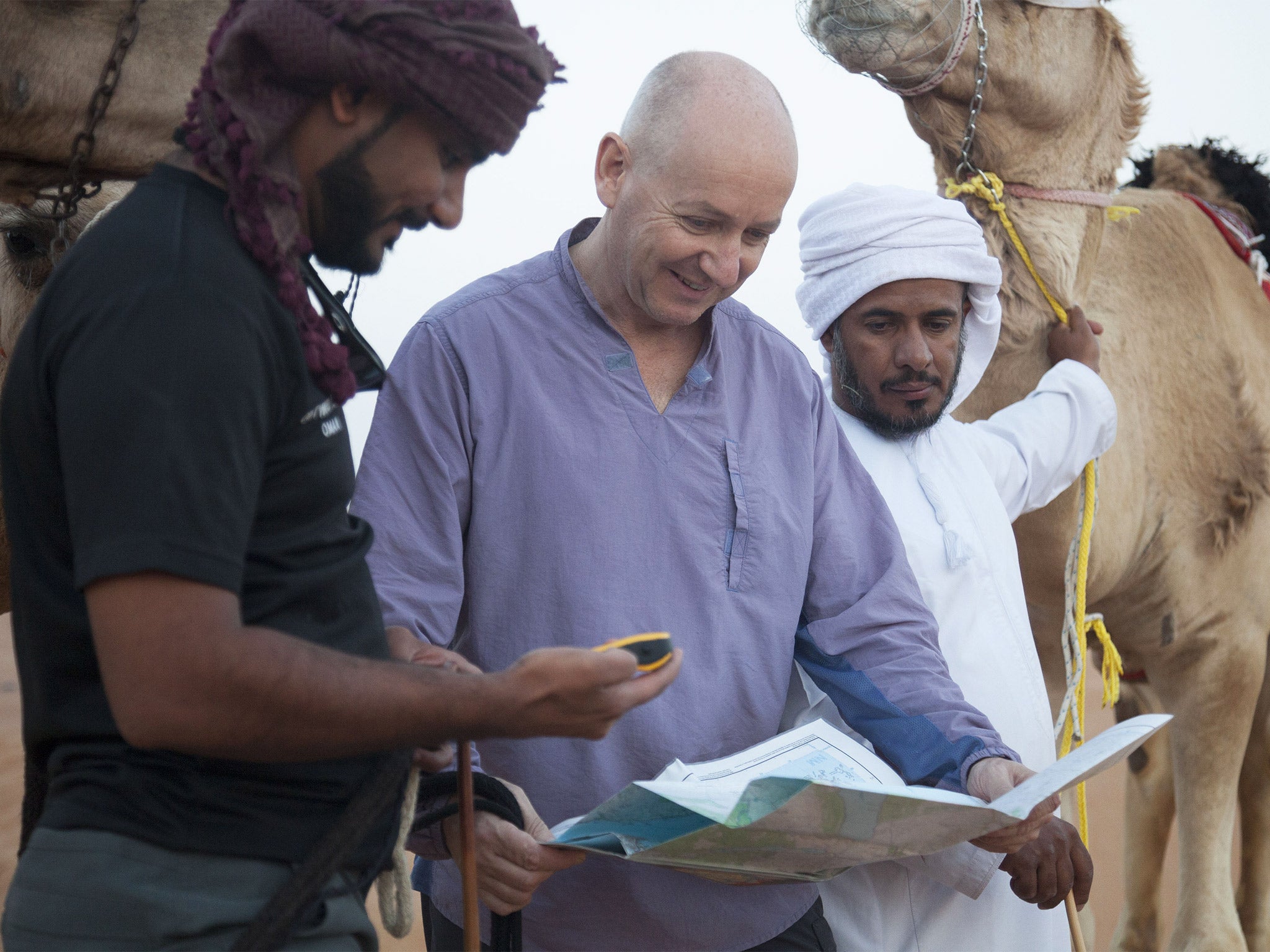

Now the memory of his voyage across the world’s largest sand desert is to be resurrected in the spirit of the man himself when an Anglo-Omani expedition sets out today to recreate his 1930 journey. A train of four camels and four walkers will leave the city of Salalah on Oman’s southern coast and trek through present-day Saudi Arabia, moving from desert well to desert well and sleeping in the open. They will aim to reach Doha in late January.

The adventure is the brainchild of Mark Evans, a Shrewsbury-born teacher based in Oman for the past 20 years who became fascinated with Thomas’s exploits.

Speaking before his departure, Mr Evans, a seasoned polar explorer, told The Independent: “There could only be one team who would be the first to walk into nothing and that was Thomas and his companions. We want to rekindle interest in these forgotten explorers. What they did was pure exploration: they had no external support and they had to live with constant uncertainty, not least whether they would even survive. We’d like to inspire others, in particular young people, with those core values of tenacity and resilience.”

Stretching across Saudi Arabia into Oman, Yemen and Abu Dhabi and fringing Qatar, the Empty Quarter covers 650,000 square kilometres of shifting sand with dunes up to 250 metres in height.

While Mr Evans and his expedition will stick to the route followed by Thomas, coaxing their camels from watering hole to watering hole, they will at least have the tools of modern exploration, including satellite phones, medical assistance and two back-up vehicles carrying emergency supplies. Thomas did not even have the security of knowing that his superiors were aware of where he was.

The Cambridge-educated administrator had served in British-controlled Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq, Syria and Kuwait) during the First World War and rapidly developed an affinity with the Middle East and its people. By 1925 he had been appointed finance minister and Wazir, or Prime Minister, to the Sultan of Oman, the first Westerner to hold such a position in an independent Arab state.

But his ministering and number crunching concealed a more primal interest in the land he was helping to govern. Shortly after midnight on 6 October 1930, a British oil tanker slipped out of the Omani capital of Muscat. On board, and incognito, was Thomas, who had arranged to be dropped off at the southern port of Salalah en route to fulfilling a dream that had become an obsession.

The scholarly Prime Minister was engaged in a race with other Western explorers to conquer the Empty Quarter. His leading rival was St John Philby, chief adviser to Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia, and father of the Soviet agent Kim Philby.

In 1929, Philby senior had written to Thomas asking him: “Are you planning an attempt on the RK? I still dream of that but from here such ventures are difficult. Yet that is the ultimate purpose of my being here.”

Philby’s declaration of intent (in the end he was prevented from entering the desert by his patron, who feared for his safety) seemingly spurred Thomas to make his own attempt.

Before arriving in Salalah he had arranged with a local Bedouin leader – Sheikh Salih bin Kalut – for a group to guide him on his way. However, he ended up waiting two months for Bin Kalut to show up after being told his would-be guides had been called away to pursue a tribal conflict.

The Englishman was on the point of giving up and boarding a ship back to Muscat (where unbeknown to him a letter awaited recalling him to London, prompted by concerns over his skill as a financial manager) when Bin Kalut and his men finally arrived and signalled their willingness to venture into the Rub al-Khali.

As Thomas later recalled: “My plans were conceived in darkness, my journeys only heralded by my disappearances, paid for by myself and executed under my own auspices.”

What followed was an extraordinary journey into the unknown, with Thomas reliant on Bin Kalut to negotiate with rival tribes to clear their passage. Living on camel milk and desiccated soup, bolstered on Christmas Day by a festive meal of baked beans, Thomas navigated by the stars and collected botanical specimens en route, more than 20 of which were new to science.

On 5 February 1931 the team arrived at Doha, then a far cry from the glittering metropolis of today. The lonely desert fort had no telegraph, forcing Thomas to sail by dhow to Bahrain before he could tell the world that the “terra incognita” had been conquered.

Mr Evans acknowledges he and his colleagues are unlikely to push back the boundaries of science. Instead, they hope to highlight what has and hasn’t changed in Rub al-Khali.

He said: “Things have changed beyond compare in places like Doha or Dubai but the Empty Quarter is emptier than it has ever been. This is an opportunity to cross political boundaries [that did not exist in Thomas’s time] and reconnect these cultures.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks