How Egypt’s Copts fell out of love with President Sisi

Sisi’s failure to address longstanding injustices has prompted disillusionment. Many Copts now feel that the president has failed to deliver on the promise of equality he made three years ago

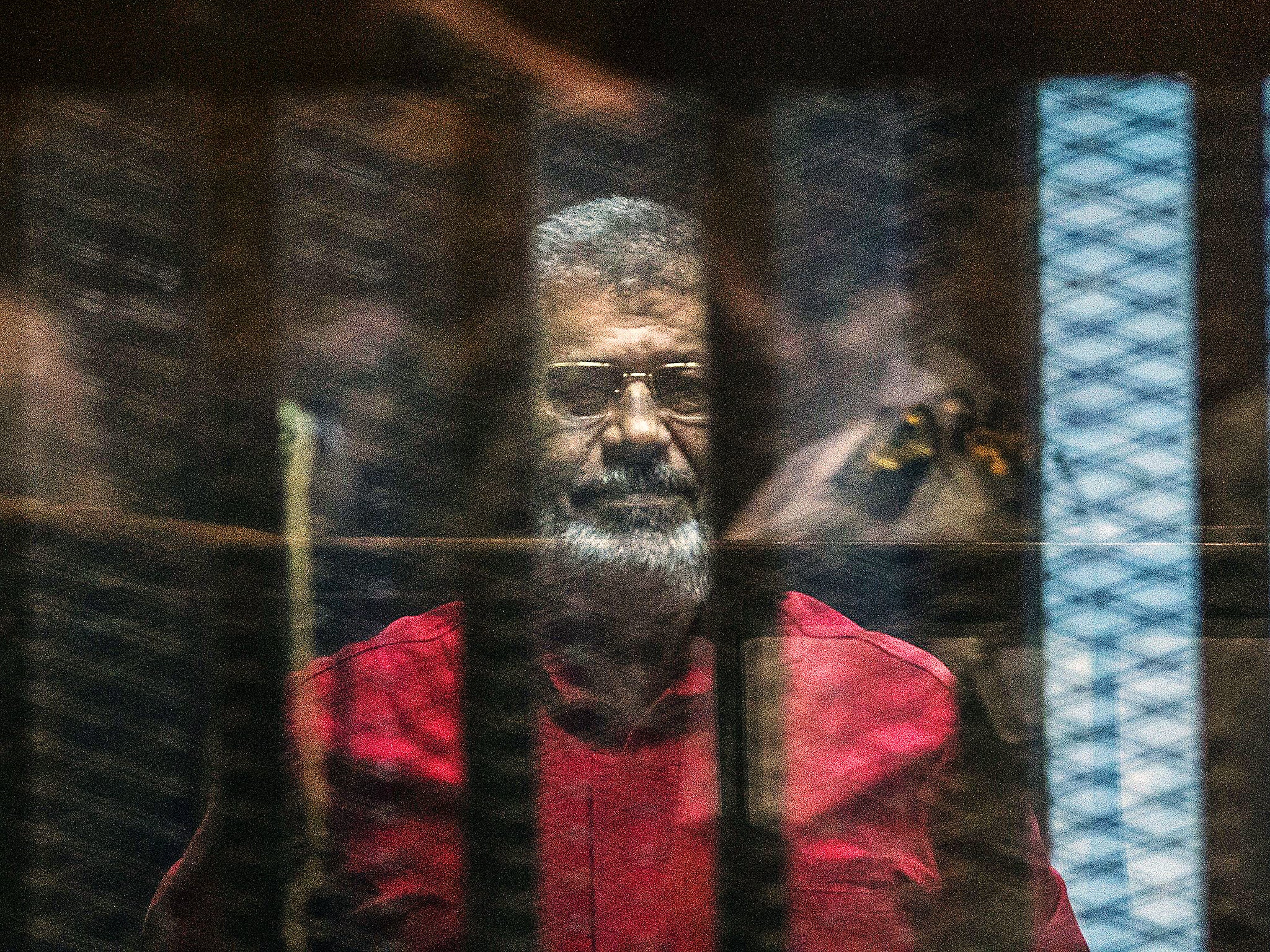

When the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Egyptian president, Mohamed Morsi, was ousted by a military coup in July 2013, the country’s Coptic Christians rejoiced. They saw General Abdel Fatah El-Sisi, who initiated Morsi’s removal and later became Egypt’s new president, as a saviour. Bishoy Armanious, a 30-year-old electrical engineer from a suburb of Cairo, was among El-Sisi’s biggest fans. Together with thousands of Egyptians, he took to the streets in support of the general.

“We had been praying for change to happen,” Bishoy muses. “El-Sisi saved Egypt from the nothingness Morsi was leading us to.”

In the early days after Morsi’s ouster, many Copts shared Bishoy’s conviction. Some, like Coptic priest Makary Younan, even claimed El-Sisi had been “sent from heaven.” But Sisi’s failure to address longstanding injustices has prompted disillusionment. Many Copts now feel that the president has failed to deliver on the promise of equality he made three years ago. In a sign of mounting discontent, protests amongst the Christian community have swollen in recent months to an unprecedented degree. Once regarded as a pillar of support for the regime, Copts now constitute a growing challenge for the government in Cairo.

Copts are the region’s largest minority and constitute about 10 per cent of Egypt’s population of 92 million. Under successive authoritarian leaders, they have faced systematic discrimination, and many feel they are treated as second-class citizens. Restrictions on the construction of churches are a perennial sore point. Copts have long had to deal with arduous bureaucratic procedures to obtain the documents needed to build, renovate or even patch up a church's toilet. Rumours of new church construction are often enough to cause an outcry and even mob violence.

Relations between the state and the church deteriorated precipitously in the 1970s under President Anwar Sadat, who openly flirted with Islamist forces and even exiled Pope Shenouda III, the Coptic Church’s head. Though the relationship recovered following Sadat’s death, the position of Copts hardly changed for the better, and the building of churches remained a bargaining chip. President Mubarak, who ruled over the country from 1981 until 2011, is said to have approved the building of 10 churches during his first decade in office. At a similar annual rate, his successor Morsi approved the construction of precisely one church.

A long-awaited law regulating the construction of churches was passed by Egyptian parliament last August. But the new piece of legislation is nothing to celebrate. As Human Rights Watch argues, the law reinforces the authorities’ control and contains security provisions that risk subjecting decisions on church construction to the whims of violent mobs. Though some clerics approved of the law, it prompted a flurry of criticism from influential Copts, who argue that it seeks to maintain the state’s dominance over the Christian community. Ishaq Ibrahim, a prominent researcher at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), condemned the bill, claiming it “empowers the majority to decide whether the minority has the right to hold their religious practices”.

Rising sectarian violence is another problematic issue. Violence against Christians peaked in August 2013, when mobs attacked more than 200 Christian-owned properties. The authorities later vowed to reconstruct the damaged churches and houses, but those promises have only partially materialise. As a result, a many churches remain in ruins, and Christians remain vulnerable. Only two weeks ago, fifteen Coptic homes were attacked in the city of Sohag by up to 2000 assailants.

To make matters worse, those who attack Christians or Coptic churches frequently get away with it. Reconciliation sessions – the method authorities favoured to resolve inter-communal disputes – have done little to alleviate feelings of injustice, commonly allowing perpetrators to walk free. Officially, such meetings are designed to foster communal peace outside the legal system, but the facts on the ground do not line up. A damning report published by the EIPR condemned the practise for fostering discrimination and exacerbating religious differences.

On other occasions, the Egyptian government has itself committed violence against Copts. The most brutal example was the October 2011 Maspero Massacre, when 28 predominantly Christian protestors were brutally killed by security forces in central Cairo. Some were run over by tanks. Making the event all the more outrageous is the fact that the protestors had been demonstrating against the torching of a church in the southern city of Aswan. The incident has since come to symbolise the state’s treatment of the Copts and gave rise to the eponymous Maspero Youth Movement – a powerful union of Coptic activists.

Despite the state’s abysmal human rights record, a majority of Christians rallied behind El-Sisi when he took control of the country in 2013. Many, like Bishoy, were nervous about former president Morsi’s Islamist rule, which they feared would exacerbate their precarious position.

With Sisi failing to live up to the expectations, however, many are now questioning the president's objectives. Protests flared this summer following a series of high-profile attacks. In one widely publicised event, a 70-year-old Christian woman was stripped naked by a mob of 300 men and paraded through the streets of her village, inducing the anger of Copts nationwide. In June, Islamist mobs assaulted Coptic families in the southern province of Minya, burned a kindergarten run by Christians, and murdered a Coptic Orthodox priest in Sinai. In July, a Christian nun from a well-known monastery in Old Cairo was killed after reportedly being hit by a stray bullet on the Cairo-Alexandria highway, and a pharmacist was stabbed to death and beheaded in Tanta.

The attacks prompted tremendous outcry. Copts across the country and in the diaspora staged protests in defiance of the regime. Families of victims travelled from across the country to Cairo in August to demand that the government protect their rights. In Washington, Copts called on the US to pressure the Egyptian government over its negligent handling of sectarian violence. Adding fuel to the fire, a number of Coptic intellectuals signed a petition in September expressing their opposition to the regime when President El-Sisi visited New York for the UN General Assembly.

In ecclesiastical ranks, too, dissent is mounting. Bishop Anba Makarios of El-Minya province has repeatedly boycotted reconciliation sessions. At one point, he accused the regime of treating Copts as as “an undesirable tribe”. Recently, the bishop also “reminded” President El-Sisi in a tweet that Copts are Egyptians, too.

The head of the Coptic church, Pope Tawadros II, has also been criticised for his support of al-Sisi. “Despite the warm relationship between the current regime and the Egyptian churches, ordinary Christian citizens ... suffer from discrimination,” the same petition criticising al-Sisi read. Government reforms implemented in the 1950s made the patriarch the Copts’s main representative in politics, paralysing the once-vibrant Coptic civil society.

Today, his failure to champion Coptic rights has fed into resentment. Disturbed by the Patriarch’s pro-government leanings, blogger Wael Eskander went as far as to question the Pope’s fidelity to the Coptic creed. “The pope and the church have shown very little [love], except to the regime,” he wrote.

The Copts’s uncomfortable position in Egyptian society reflects the country’s descent under President Sisi. In recent months, the Egyptian economy has experienced a currency crisis even as the government continues to grapple with Islamist militancy. The 2011 revolution carried a promise of change, but led only to stagnation – and not only for Christians. The economy has hit everyone’s pocketbooks, and minorities such as Shia Muslims, Nubians, atheists and the country’s LGBT community suffer far greater persecution than before. Numerically, the Copts constitute a minority. But their suffering is shared by most Egyptians.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks