Independent Appeal: Rappers who speak their minds in the name of peace

Hip-hop music is helping heal the wounds in post-conflict Lebanon

John Lennon springs to mind, or perhaps a youth orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim. But hip-hop as the music of peace? It sounds implausible that a genre often associated with glorifying violence could help spread the "give peace a chance" message. Lebanese rap, however, is different.

In a small crowded bar in Hamra, West Beirut, an appreciative young audience is enjoying FZ's beatboxing and the rapping of MC Yassin (aka Yeah-Seen). The reconstructed Lebanese capital now has as many live music clubs, fashionable cafés and hedonistic party venues as it used to have bombed-out buildings. But this Beirut crowd is getting entertainment with added political commentary. Yassin's words express disgust at conditions that Palestinian refugees like him must endure in Lebanon. "I lived all of my life dreamin' but the dream is over. Whenever I ask for a job, they tell me, 'No you're Palestinian!'."

"Rap here has nothing to do with gang culture or bling," the event's organiser, MC Edd (aka Edouard Abbas) explains through a haze of cigarette smoke. A "very political emmcee" as he describes himself, Edd was born in French-speaking Ivory Coast but uses Arabic-language rap to attack the sectarian nature of Lebanese society.

It was precisely hip-hop's ability to reach across these sectarian divisions that drew the attention of Permanent Peace Movement (PPM). Founded by students in the aftermath of Lebanon's 15-year civil war and now among international peacebuilders promoted by Peace Direct – one of the charities in this year's Independent Christmas Appeal – the small NGO trains community leaders in defusing tensions and equips people with the skills to articulate grievances without resorting to violence.

One of its most eye-catching initiatives is to recruit the arts for the purposes of reconciliation. Last year PPM persuaded hip hop artists including Yassin and Edd to become unlikely (and sometimes unruly), messengers for non-violence.

The project resulted in probably the world's first hip-hop album about peace, itself a remarkable achievement, and the recording is now a valuable peace advocacy tool, according to Raffi Feghali, PPM's energetic arts coordinator. Peace Beats includes tracks such as Edd's "Salem Nafseh" (Inner Peace) and another by a group called BeiruTus which goes: "Salam keep your hands up, Salam, don't you ever give up, Salam put your white banners up".

The album's only female hip-hopper Chantal Harmouche (who calls herself Venus) said with her contribution "Entifada lal Salem" (Intifada for peace) that she wanted to "wake my people up!", while Zoog, a 19-year-old emcee raps sagely: "I still say it, some day it'll be OK, it's why I don't walk around with a mean old face".

The Lebanese are still recovering from a time when their country embodied the cliché "war-torn". So divided is the nation that there are 18 official religions. Those born after the civil war experienced the horrors of the 2006 Israeli attacks on Hezbollah in which nearly 1,000 Lebanese civilians died, and clashes between Sunni and Shia armed groups reached the streets of Beirut the following year. More than 400,000 Palestinian refugees, meanwhile, are barely tolerated and endure a tense relationship with Lebanese nationals.

Religious differences may not be so relevant for the younger, urban generation, Feghali points out. "We all have friends who are Muslims, Christians or Druze. But even the young Lebanese need to be educated about conflict, because it's so easy to be sucked into sectarianism here."

An actor and musician as well as a peace worker, Feghali admits that embracing hip-hoppers as ambassadors for peace was a gamble. "Hip-hop culture has a negative vibe around it. But we felt it could be great way to reach young people," he says.

Getting the artists to work together was not easy. "They could rap about anything as long as it came under the umbrella term 'peace'. We didn't want to censor them but I left it to their conscience that in their lyrics they would represent the values PPM espoused."

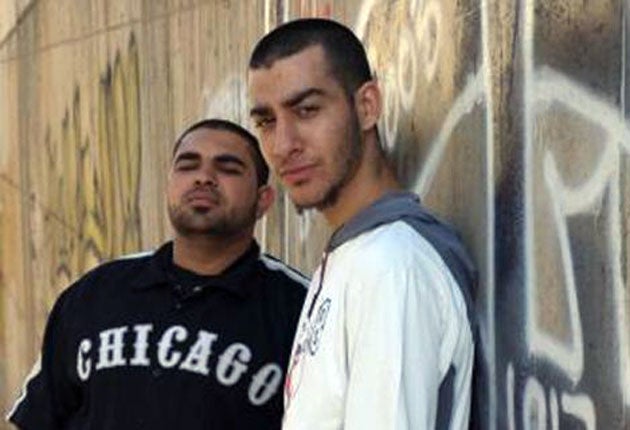

Yassin, who is one member of the Palestinian rap duo I-Voice (the I stands for Invincible) struck a more pessimistic note than the organisers expected, because realistically he doesn't expect the Israel-Palestine question to be resolved any time soon. That honesty doesn't worry Feghali. "The language on the album is not what you'd call 'soft', but the rappers learned that peace advocates are not weak; they can be aggressive in spreading a positive message." And the collaboration has influenced everything the artists have done since.

The hip-hoppers are "the pride and joy" of this small NGO's achievements he adds; they received training in conflict resolution, in the use of alternative media such as mobile phone videos, and they continue to help out by sharing their experiences with other cross-community arts groups like painters, poets and actors. Feghali is currently seeking funding for a project to apply the skills of improvised theatre to conflict prevention.

"One of the principles of 'Improv' is that you accept whatever your co-actor says to you with the words: 'Yes, and...' Another is that each one's priority is to make his co-actor the star. In daily life this could be transformational. It goes way beyond positive thinking," he says.

Such ideas may sound fanciful amid the brutal realities of life in Shatila, a slum for Palestinian refugees in the south of Beirut, where overcrowding is shocking and violence between rival factions routine. But PPM is helping train camp residents in "life skills".

Disputes in the Palestinian camps are often over water, electricity or the dumping of garbage. But they can fatal consequences, Sonia Nakad, PPM coordinator, says. "It goes straight to guns. That is how people deal with things."

One idea she's working on is a scheme to get parents to reject plastic guns as toys. "If two kids are fighting over a ball," Nakad says, "One will pick up his toy gun and 'shoot' his friend because that is what he has seen his Dad or his uncle doing."

Yassin of I-Voice is proof that even in these bleak ghettoes awash with real firearms, the young can find peaceful ways to articulate their concerns. He lives among 16,000 others crammed into the Bourj el-Barajneh camp for Palestinian refugees near Beirut airport. Overcoming a lack of electricity and money, I-Voice have set up a makeshift recording studio in a converted shack and are starting to enjoy international attention.

Performing solo at the small hip hop event in Hamra, the self-taught Yassin, still just 20, is strikingly confident on stage as he lays into the big international rap stars over-glamorising and commercialising the genre. "Hip-hop is a way of defending yourself," he explains later at the bar. "It came out of the struggle of black people in America, but it's the same for the Palestinians. I want to tell people about what is happening to our people."

"Hip-hop has educated me," he adds proudly. "It's made me read the history of other peoples struggles." Yassin does believe in peace, he insists, "as long as it's peace with justice". And talking is always better than killing. As he raps on the album: "As far as a bullet goes, my voice goes further".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks