Russian forces are the latest to travel on Syria's Roman road to barbarity

Only now, some three months after the Russian-aided Syrian army retook Palmyra, are the full horrors of the Isis regime coming to light. But, as Robert Fisk writes, the ongoing battle to banish Isis means there is no end to the atrocities in sight

On the highway to Palmyra, across the desert from Homs, a Russian armoured convoy shimmered in the heat. The landscape is a grey, gritty, hostile sand that stretches all the way to Isis-land, not like the soft yellow dunes of the Gulf, but the Russian soldiers seemed unperturbed. One stood on the roadway, as tall as a Serb, automatic rifle on his right arm, US-style shades over his eyes, grinning at us beside his armoured personnel carrier.

It’s strange how a Westerner reacts to the Russian army these days. Weren’t these the sons of the guys who invaded Afghanistan in 1979 – another “limited intervention” I recall at the time – and were these not the very same soldiers who are now in the Crimea? Yet we are ambivalent, we lonely Westerners in this dangerous desert. Out in this oven sand-field, with Isis and their motor-bike attackers only a few miles on each side of the highway, I must admit it’s a tad reassuring to see Putin’s lads on the road.

They are a mine-clearing unit and the Russians with their white European faces, watching us with self-confidence from their trucks, have been clearing the streets of Palmyra. “No mines,” it says in Russian on every street corner in big red paint. The Russian base in Palmyra, a stone’s throw from those tortured ruins of Xenobia, is safe from Isis’s network of explosives and underground booby-traps. For now.

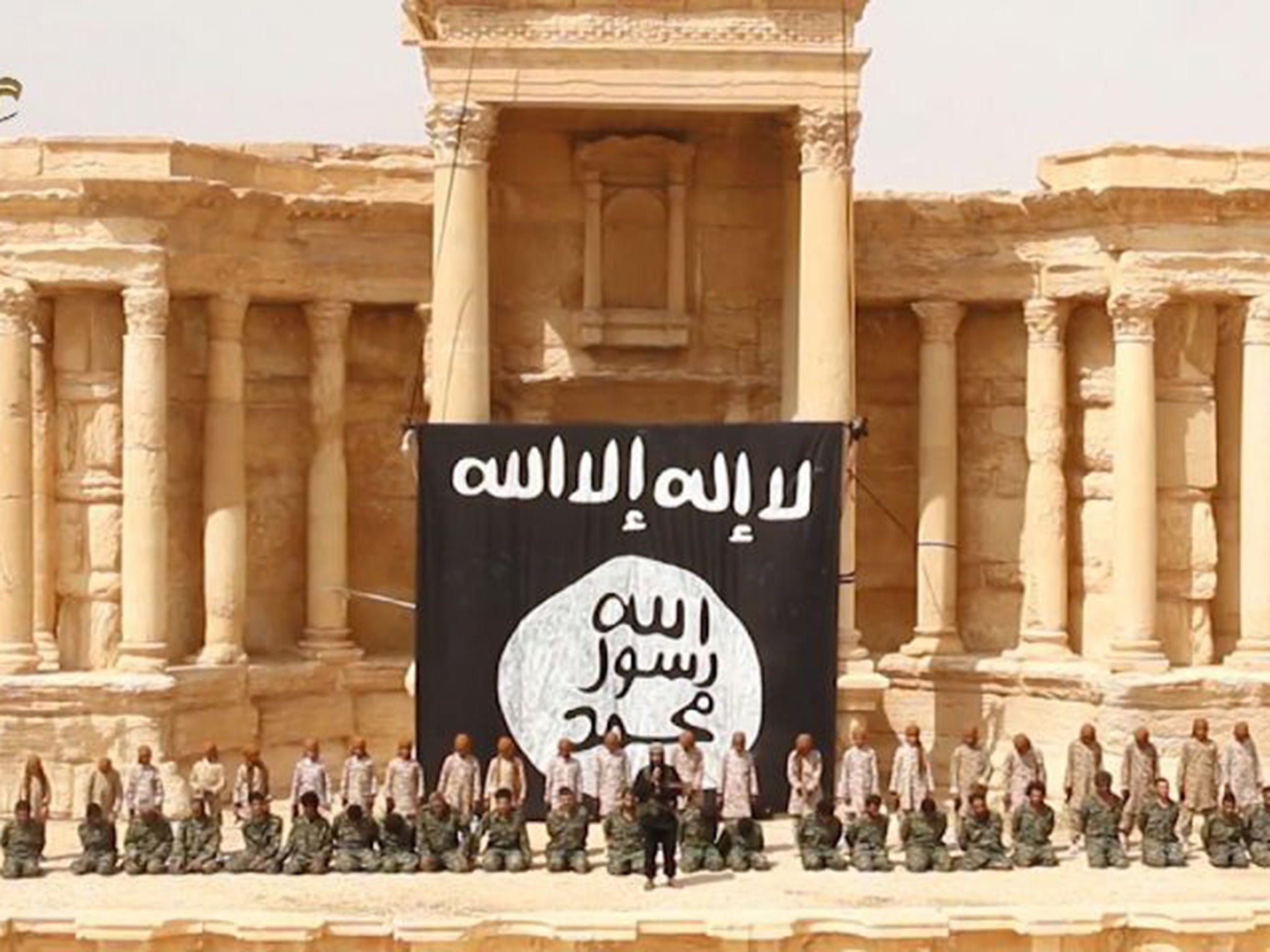

But Palmyra is a mournful place. A few civilians have returned, but dust blows the garbage down haunted streets. I find the mosque, outside of which a dozen men were lined up and ritually beheaded in streams of blood after Isis captured the city. A picture of this atrocity, twice cropped to keep the ghouls at bay, appeared in The Independent. Not a trace now, of course, of suffering or horror, just a flyblown intersection, a twisted metal sign and the baking heat. In the ruins of the Roman amphitheatre, we notice a rope tied round the top of a Corinthian column with a small loop underneath to hold a noose – Isis’s handiwork, too obscure and high for Palmyra’s liberators to cut it down.

This is not a place where named Syrian generals talk openly of their May liberation of the ancient Roman city with Russian military help. I am introduced to an unsmiling, tough Syrian army intelligence officer, a general whose office walls are adorned with two photographs of him in uniform alongside a young – and an older – Bashar al-Assad. No names are offered for this man, although he fought in the last days of May 2015 when the Isis legions struck the city: 40 of his colleagues fought to the end. They are officially listed as missing in action but the general is still trying to find their mass grave.

“Daesh [Isis] destroyed all civilian life here,” he says. “They destroyed water, electricity, communications, the municipality building, the museum. Even when we liberated the city this year in ‘Operation Badia’, we had delegations from the UN and the Syrian Red Cross and Russian journalists who had been told that Isis had re-entered Palmra and that our army had fled. This was Isis propaganda.” The Arabic “badia” means “unique”, not a bad name for a Syrian-Russian ground and air operation to recapture a Roman city.

And when I ask the intelligence man if he could have recaptured Palmyra without Russian help, he does not hesitate. “No!” he says. “We do not forget that we are a country at war for five years. We aren’t fighting other states. We are fighting terrorist organisations from all over the world with very sophisticated weapons. Even the intelligence organisation of the US and Britain are at the source of these operations. The air and bombing support from the Russians is a very great help. We could continue without them, but it would be much harder.”

To “continue”, the general is talking about an advance into the heartland of Isis-held Syria. He doesn’t see this being as difficult as the bitter struggle to retake Palmyra. “Mountains surround Palmyra from the east, west and north. In March, we had to move our tanks into the mountains. But the way to Deir ez-Zour is flat, and we will be able to destroy the power of Isis. Towards Deir ez-Zour are the resources of Syrian minerals under Isis control, but now we have already got back all of the Jezal gas field and the fields north of Palmyra.”

Though surrounded by thousands of Islamist fighters, the city of Deir-ez-Zour and its civilian and military airfields are still under Syrian army control. The general speaks of the strategy used by his men to strike outside Palmyra, to hit suicide trucks and armour with tank fire rather than let their opponents reach their front lines. He holds out a picture of a heavily armoured truck in which Isis placed a huge bomb but whose suicide driver could only move a few hundred yards before it sank into the sand – where Syrian engineers defused the tons of explosives inside.

The dead Isis fighters are from Chechnya, Afghanistan, Pakistan – there were a few Kuwaitis and Qataris but also many Saudis, the intelligence man says – and their bodies were buried by his army “in a proper way, in sharia law” in a Muslim cemetery, the general insists. That would certainly be a change from other Syrian battlefields, where the men whom the government calls “terrorists” are left unburied to be eaten by dogs. Some of the dead foreign fighters are dragged away by Isis – an odd tactic noticed over several years in Syria, sometimes adopted with the use of hooks to extricate corpses – while others are burned by the Islamists after they die.

Intriguingly, the general believes that the Nusrah Front is now in some ways more powerful than Isis. “Perhaps Nusrah are more powerful because they have better, more sophisticated weapons, but Isis is in other ways more powerful because the area it controls is bigger and has a greater money supply from the oil and gas fields they have.”

But I return to the old question: what is Isis? Here is the general’s reply: “The ideological doctrine of Isis was well prepared in areas which have a suitable environment for Takfiri ideology [Muslims who accuse others of apostasy]. The ‘takfiri’ of all sects are ‘kafirs’ [non-Muslims], even Islamic groups and all other [Muslim] sects that don’t believe in Isis. These people have been brainwashed with the seeds of this ideology. Conservative Muslims began to wash their brains by violating the true ideas of the Koran.

“If a young man has a sexual intent, they tell him ‘if you fight, you see the houris’ [beautiful young women] and even in life the man is told that if he lays his hand on every woman he meets and says ‘alahu akbar’, she will be under his control. Even the young women they allow to make ‘jihad’, they will join with the man. They even have ‘fatwas’ about the interests of men – to have cars or houses – and they give them drugs that help them fight without sleep for three days. The purpose of the drugs is to make each of them into an unnatural person.”

The general says he fought with his intelligence units for eight days when Palmyra was attacked at 9.45pm on 12 May last year. “The decision was taken to leave in order to spare the civilians and the Roman ruins. Isis came with 2,500 men and with very many car bombs and they attacked from five directions, including from Raqqa, the Wadi Abiat Dam, from the T3 gas station and the countryside of Hama. My 40 operators here fought on and they are now still missing.”

The Roman ruins lie as they did when the Syrians and Russians retook Palmyra last March. The temple of Bel can never be rebuilt from the cracked and crushed stone that lies in tens of thousands of pieces around it, some of the ancient lintels splintering upwards into the Roman columns of nearby colonnades and smashing hunks of them on to the ground.

And the amphitheatre remains a place of darkness even in the harsh white sun of the Syrian summer. The first executions on the Roman stage were of 25 Syrian soldiers, each killed by a young Isis boy who shot them in the back of the head with a pistol. The second execution session of 25 men included both soldiers and civilians.

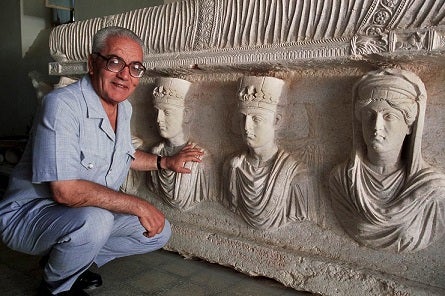

The back of an iron door behind the theatre is decorated with a stencilled picture of Khaled Asad, the 82-year old director of antiquities decapitated by Isis in August 2015. They hung him from a Roman pillar, carefully replacing his spectacles on his severed head.

And high up on a roman pillar at the back of the stage, you can still see a rope circling the column and a small loop to hold a noose. The Romans were just as cruel, of course. In one sense, Palmyra returned to its bloody history last year, and the modern slaughter will now have to be accepted – like the stones of the Temple of Bel – as proof to future visitors that we can still descend to the barbarism of antiquity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks