Syria in 2016 will be like the Balkans in 1914 as explosive violence breaks out on an international scale

The cost of intelligence failures is rising as the Middle East enters a more violent phase

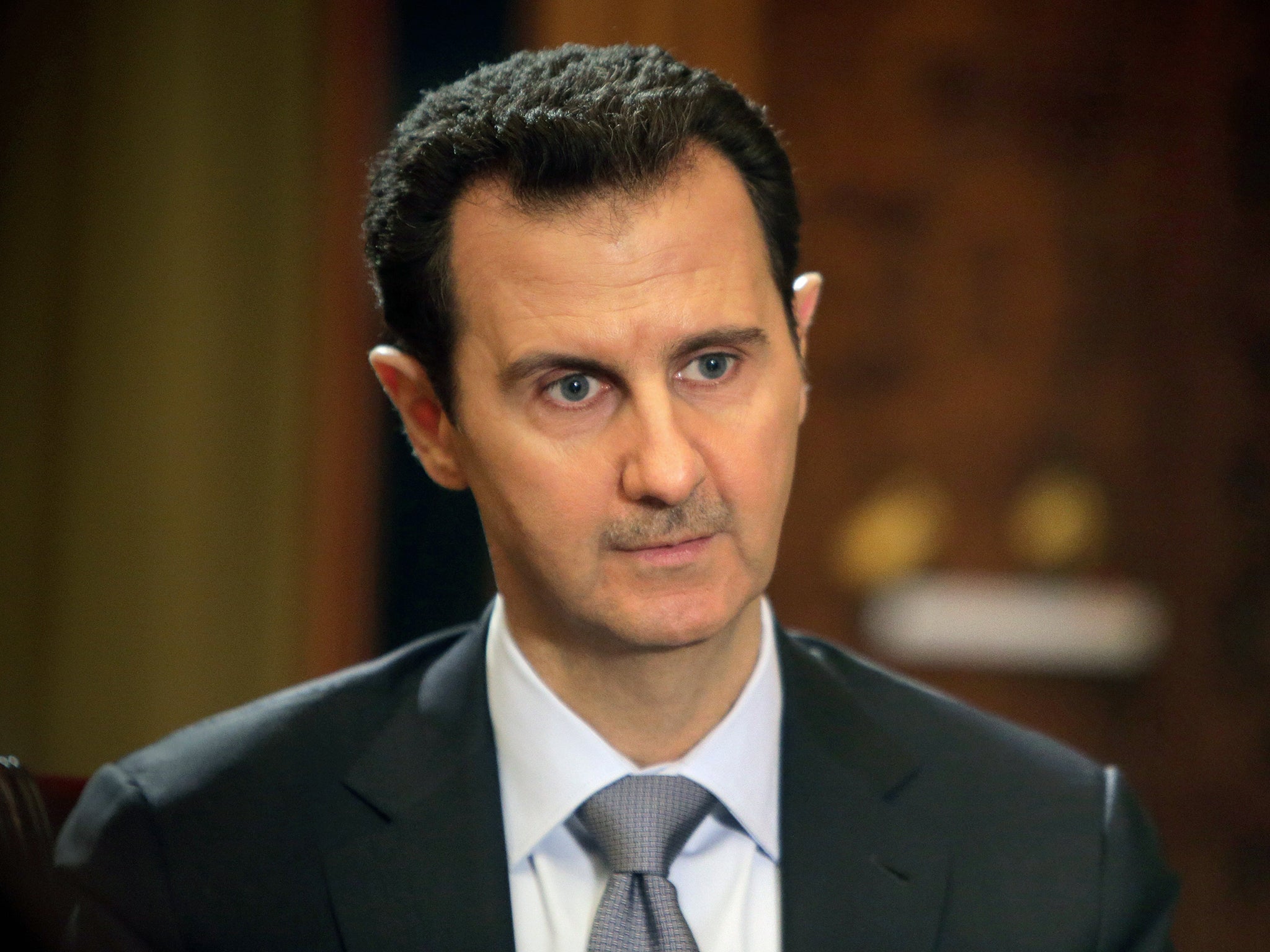

The CIA analyst is confident about what is likely to happen in Syria. He says that “Assad is playing his last major card to keep his regime in power”. He believes that the Assad government will step up its efforts to prove that its enemies “are being manipulated by outsiders”. The probable outcome is a split within Syria’s ruling elite leading to Assad being ousted, though he admits that there is no obvious replacement for him.

The reasoning in the CIA special analysis, entitled “Syria: Assad’s Prospects”, is sensible and convincing, though overconfident that Assad’s days are numbered. The extent of this overconfidence is highlighted by a glance at the date of the document, which is 17 March 1980, or 35 years ago, and the President Assad, whose imminent political demise is predicted as likely, is not Bashar al-Assad but his father, Hafez al-Assad, who died in 2000. The analysis was released by the CIA under the Freedom of Information Act in 2013.

The CIA paper is an interesting read, not least because it shows how many ingredients of the present crisis in Syria have been present for decades, but had not yet come together in the explosive mix which produced the present horrific war. In 1980, the writer assumed that Syrian politics revolved largely around the sectarian differences between the Alawites, the Muslim sect to which the Assads and Syria’s rulers generally belong, and the Sunni Arab majority. The analysis is written in an upbeat tone as it forecasts that splits between the two communities may bring Assad down.

The CIA certainly wanted Assad gone and had some ideas about how this might be achieved. “Army discipline may well collapse in the face of widespread riots,” it says. “This could lead to bloody war between Sunni Muslim and Alawite units. The Alawites, however, may choose to topple Assad before such turmoil develops in order to keep their position secure.”

This last sentence could have been written at any time since 2011 as a summary of what the US would have liked to happen in Syria: it has always wanted to get rid of Assad, but it does not intend to destroy or even weaken the Syrian state and thereby open the door to Isis and al-Qaeda. Even super-powers sometimes learn from history, so the US and its Western allies today hope to avoid a repeat of the disastrous disintegration of Iraq state institutions in 2003 after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. Tragically, the unnamed CIA analyst eventually got the sectarian civil war he had half-hoped for, but Assad is still there and Syrian people have got the worst of all possible worlds.

US intelligence chiefs are far more outspoken these days than their counterparts in Britain about the calamitous consequences of US-led foreign interventions over the past 12 years. None more so than General Michael Flynn, recently retired head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, the Pentagon’s intelligence arm, who says bluntly in an interview with the German magazine Der Spiegel that the Iraq war “was a huge error. As brutal as Saddam Hussein was, it was a mistake to just eliminate him. The same is true for Muammar Gaddafi and for Libya, which is now a failed state. The historic lesson is that it was a strategic failure to get into Iraq. History will not be and should not be kind to that decision.”

Big players such as the US can more easily afford to admit mistakes than those, like Britain, which are smaller and lacking in confidence about their great-power status. But there is a price to be paid for remaining mute or in denial about past political, military and diplomatic errors. If it is admitted that anything went wrong for Britain in the Iraq, Afghan, Libyan and Syrian wars then it is only in the most general terms. A former diplomat at the Foreign Office says that it was striking how in the years following the Iraq invasion of 2003, he heard “almost nobody in the Foreign Office talk about the decision to go to war or what went wrong”. This may have been because most officials privately opposed the war from the beginning as a bad idea, but did not want to say this publicly, or even within the office.

It is a natural British personal and institutional instinct to hush things up, but after four wars marked by British government blunders and misjudgements, it is curious that information from the intelligence services is not treated with greater scepticism. A recent sign of this was David Cameron justifying his unlikely claim that there are 70,000 moderate anti-Assad fighters in Syria by saying that this figure came from the Joint Intelligence Committee, as if this sourcing put its accuracy beyond doubt. It may be that endless harping on British success in breaking German codes in both world wars has combined with a diet of James Bond movies to exaggerate the reputation of British intelligence.

Foreign political leaders are often more dubious about what their intelligence services really know. Before the start of the Iraq war in 2003, President Jacques Chirac told a visitor that he did not believe that Saddam had any weapons of mass destruction. The visitor said: “Mr President, your own intelligence people think so.” Chirac replied: “They intoxicate each other.” In other words, intelligence services often become echo chambers for obsessive beliefs that are detached from reality.

The very secrecy with which they shroud themselves is useful when denying responsibility for failure. It also makes them vulnerable when governments or their own senior officers want to suppress or doctor politically inconvenient advice.

Early last year, President Barack Obama dismissed Isis, which was beginning to make spectacular advances, as being like a junior basketball team wanting to play in the big leagues. Soon after, it captured most of northern Iraq and eastern Syria. One of the reasons this may have happened was exposed this year when 50 intelligence analysts working for the Pentagon signed a joint letter of protest. They said that their intelligence findings that Isis was getting stronger and not weaker as the White House claimed, were being suppressed or doctored by their chiefs.

This was par for the course. The personal or institutional interests of the heads of intelligence agencies or any other government department are seldom served by bringing bad or contradictory news to those who decide on buRudgets and promotions. Most of the time this does not matter but today it does, because the stakes are rising in the war in Syria and Iraq. Knowledge of what is happening on the ground should be at a premium.

Serious powers such as Russia and Turkey are being sucked in and have invested too much of their prestige and credibility to pull back or suffer a defeat. Their vital interests become plugged into obscure but violent local antagonisms, such as those between Russian-backed Kurds and Turkish-backed Turkomans, through whose lands run the roads supplying Aleppo. The Syrian-Iraqi conflict has become to the 21st century what the Balkan wars were to the 20th. In terms of explosive violence on an international scale, 2016 could be our 1914.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks